Lewis Carroll 150: A look back ‘Through the Looking-Glass’

By Olivia Van Guinn, July 7 2021—

Time makes no sense to me. Fahrenheit 451 was first published almost 70 years ago? World War One was 107 years ago? Really? Now, in the year 2021, it’s the 150th anniversary of Lewis Carroll’s classic children’s book Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There, meaning the book isn’t a thousand years old? It feels like centuries between me and Lewis Carroll, but it turns out that a single Galapagos Tortoise could have met both of us in its lifespan.

We all grew up alongside the Alice mythos in one way or another. Maybe we read the books as kids. Maybe we read them as adults. Maybe we loved the animated Disney version and hated the Tim Burton version — or hated the animated Disney version and loved the Tim Burton version but in either scenario agreeing that the live-action sequel was trash. Maybe we read The Looking Glass Wars or played Alice: Madness Returns. But through all this, it’s worthwhile to stop and ask:

Why?

We’re talking about children’s books. They don’t even make sense. There are hundreds of attempts to find some deeper meaning in the narrative, but none are convincing. Undoubtedly, there are thousands of nonsensical kids books lost to history, so why did the Alice mythos survive? Why does the world care so much about these meaningless books?

To start, Carroll inhabited a social climate very different, yet in some ways similar, to our own. Early-1800s England was a land of great social change — therefore there were many warring opinions on the purpose of art. One emerging branch of thought was that art can be used to convey moral religious messages, particularly in children’s literature. Diverging from this was the branch of aestheticism, which advocated for simple beauty above any other quality. A radical form of this was aesthetic hedonism — essentially, if one enjoys viewing a piece of art, it is good art. If one does not enjoy viewing a piece of art, it is bad art. None of these opinions were all-encompassing or entirely right. For example, if the purpose of art is moral messaging, is interior design art? If an unpleasurable viewing experience makes art bad, then are all horror movies bad art? There are certainly people today who think so, but also many who would disagree.

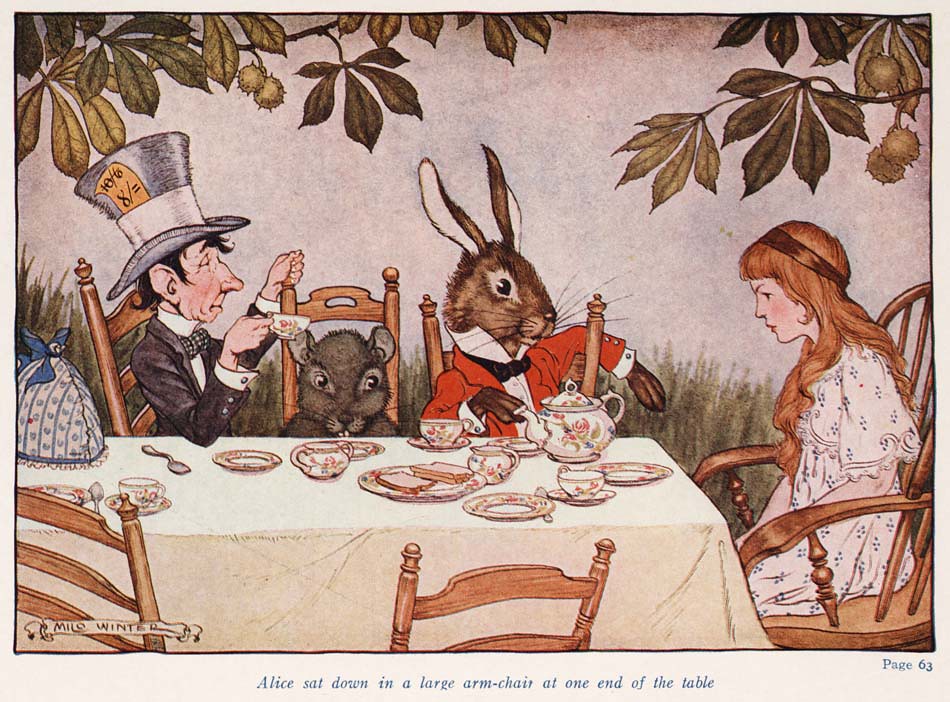

To this warring artistic landscape, Carroll produced Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, a nonsensical children’s bedtime story about a little girl who goes down a rabbit hole, meets a Cheshire cat, hears a poem about the Jabberwocky, dances with lobsters and is put on trial by the Queen of Hearts. Alice attempts over and over to rein in the chaos and maintain some level of understanding and logic in Wonderland, but each attempt only ends with the admittance that Wonderland is absurd, nonsensical and meaningless. And isn’t that great? Carroll gave a gift to children and adults — the ability to withdraw from the mainstream art argument and see something that wasn’t deep or impactful or beautiful or religious, but just plain fun. Alice doesn’t rebut any of the arguments about art but separates herself from it entirely.

In a way, Carroll was prophetic. Only the year before Alice was published, Notes from Underground by Fyodor Dostoevsky, the first existentialist novel, was out in the world. The ideas spread quickly, and throughout the next century, existentialism took the world by storm. People everywhere began to wonder, what is existing? What does it mean to exist? And many of them concluded that existence is kind of ridiculous.

Franz Kafka, like Carroll, was an author who embraced the meaningless and the absurd. But unlike Carroll, Kafka found his artistic expression restrained by the bureaucracy-obsessed environment he grew up in, shackled to a desk and forced into an office. Rather than warring over the final product of art, Kafka’s environment shunned art altogether in favour of productivity and industriousness. People back then shared an opinion many people have today — that art is not necessary. What we know as the Kafkaesque is a combination of Carrollian whimsicality and early twentieth-century bureaucracy. In one of his stories, a man is magically transformed into a giant beetle in his sleep, but when he wakes up, he can only worry about getting to work on time. In another, Bucephalus has survived to the modern-day, but he now works in an office. In one of Kafka’s novels, there is a looming castle in a mysterious village guarded not by armed soldiers, but by endless paperwork. Kafka’s works are tragic, an indictment of those who refuse to see the value of Carrollian whimsicality and trap it behind a wall of industriousness and productivity. They are a plea for this fun to be let free.

As an aside, one popular interpretation is that the Alice stories are a metaphor for puberty. This is very funny to me because personally, chessboards and playing cards were not a significant part of my development. Also, a large part of this theory is contingent on “painting the roses red” being a metaphor for period blood, which doesn’t make sense because in the original story, the ones painting the roses are three male playing cards, and any further attempt to make this metaphor work just makes you sound really weird.

Building on of Kafka’s ideas, in the mid-twentieth century was Albert Camus, who also embraced Carrollian absurdity, but gave us the most famous argument in favour of it. Camus’ time was the heyday of existentialism, and with it, the growing idea that existence was ridiculous, absurd and meaningless. However, some — such as the bureaucrats of Kafka’s day — insisted on finding some inherent meaning in life, as if this were the only thing that would make life worth living. In his book, The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus likens this search for meaning to the act of endlessly pushing a boulder up a hill — the goal as a form of captivity. Isn’t this meaningless? Camus asks. Isn’t life meaningless and ridiculous and absurd — and wonderfully so? Does it not make more sense to embrace absurdity than spend eternity trying to rein it in?

Camus takes us to the present day. We’re in the process of recovering from a pandemic that stole a year from our lives for no reason at all. We’ve suffered from poverty and sickness and death and broken relationships when we’ve done nothing to deserve it. In a time as ridiculous as this, it seems natural to try and find some meaning in it. And in doing so, a huge number of people have turned to Albert Camus’ novel, The Plague.

The Plague is a wonderful read — among many other reasons — for the haunting accuracy with which it describes the step-by-step stages of the city’s overtaking via plague. “How little we have changed,” makes one ponder, which is either a sweet, humbling or horrifying thought. But beneath that, The Plague is a novel that takes events familiar to us, commonly understood as beyond-human and reintroduces them to us in a way that is entirely and comfortingly human.

The pandemic we have been facing for a year and a half is a real-life example of Carrollian absurdity. All around us, perpetually, we face Carrollian absurdity in meaningless, chaotic phenomena like death, sickness, heartbreak — the pandemic is only a microcosm of this absurdity. In the midst of all this, we may seek meaning but we will not find it. In this way, we are like a little girl who has chased a white rabbit down a rabbit hole and is trying to make sense of a world that goes out of its way to rebel against every form of logic. We can try to rein this in with our rudimentary attempts at understanding, but ultimately, we must concede to the absurd. And in a way, this is a relief.

To understand the Alice stories, means understanding the endings as well. Alice is pushed around and prodded. While some denizens of Wonderland are friendly yet oblivious, others are mean-spirited and spiteful. Carroll does a beautiful job painting every sort of frustration, impatience and anger within the story, but in the end, Alice always returns home alright. All of it was ridiculous but meaningless and Alice’s recognition that it was meaningless means that it holds no power over her. As long as humans tell stories, there will be stories about the big triumphs and defeats, the disasters and miracles that have left an indelible mark on the human psyche. There will be stories that look at what humanity has done, what it can do, why we should or shouldn’t, but Alice is precious to us because she represents a comfort that we have turned to for centuries — that ultimately, life is quite ridiculous and meaningless. And when it becomes impossible to understand life, the only logical idea left is to go along with it, knowing we’ll come out of the looking-glass in the end.