Tighten up: focus, students and ADHD

By Tobias Ma, September 25 2014 —

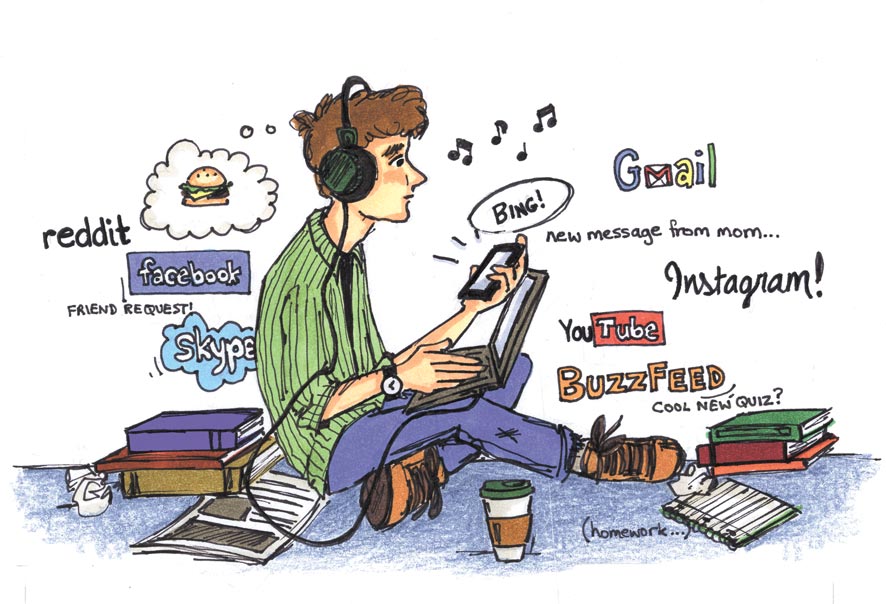

In the next few weeks, the library will fill up. Summer’s last rays of daylight will burn the sidewalk, the sound of Vitamin D splattering on the asphalt drowned out by the rustle of pages and shallow breathing next door in the library. Students will stare into the glow of monitors, scratching out notes, losing their pens, tapping their feet, texting. Intelligent people in the physical prime of their lives, hunching their spines, parsing through a deluge of information with the hope that they can hack it through the next test, hack it through the next semester and through the degree for the job at the end of the tunnel, a job that will require more of the same. Staying focused these days sure is tough.

A 2013 study by the National Center for Biotechnology Information suggested that the average attention span is now eight seconds. The same study cites a goldfish’s as nine. By the time you’ve finished reading these words, you might be thinking about sex, sushi, homework, bills, friends or sex.

The consequences of a shortened attention span range from trivial to deadly, as a slip of the wheel could mean the difference between a missed garage sale and a smouldering wreck.

These consequences have hit the younger generations the hardest. Watching a classroom full of preschool children is terrifying. Children and teenagers have access to electronic pleasures beyond the wildest science fiction of our parents’ heyday, and some of these addled youths will be the surgeons of tomorrow, cutting the brains out of our heads to plug into virtual reality vats.

Many of you know what it’s like to be aware of some task that you should have done, with full knowledge that it would have benefited you in the future. Except you didn’t do the task because Facebook was more interesting at the time and because work is so goddamned boring.

Derek Luk is one of the mental health coordinators at the University of Calgary Wellness Centre. I’ve met Luk before, and he speaks with a serenity that suggests truth to what he preaches — the promise of inner peace by making simple, consistent changes in habit.

“I think there’s been a rise overall in the diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and the use of stimulant medication,” Luk says. “Concentration and attention is quite a complex matter because you have to make sure that you’re emotionally balanced and that you have ways of dealing with stress in your life, like maintaining good nutrition. There’s no one fix.”

According to the Center for Disease Control, the diagnosis of focus problems like ADHD are on the rise. Nobody is quite sure of the reasons behind this trend, or if it reflects an actual increase in cases versus more frequent diagnosis. Technology appears an obvious scapegoat for decreased attention spans. According to Luk, people use social media as a form of stress relief. The problem is that this kind of fix doesn’t make you feel better in the long run or give you coping skills.

“Your dopamine goes up when you use social media,” Luk says. “It affects the chemistry of your brain. And people who multitask on their laptop or tablet perform worse than people who work at one thing at a time.”

Perhaps Calgary youth rely on phones to an exceptional degree. Calgarians live in a wealthy but sprawling urban environment with only a few centralized social hubs, such as Stephen Avenue, Kensington and Marda Loop. Canadians have amongst the largest bubbles of personal space considered comfortable. The amount of open area here could have maladapted us to the congestion of places such as the C-train, making cellphones an attractive escape from social claustrophobia.

Daniel Goleman, a psychologist and author of the groundbreaking book Emotional Intelligence has released a new work titled Focus: The Hidden Driver of Excellence (feel sorry for this man’s children), which argues that those who are able to focus succeed more than those who can’t, differences in natural talent and processing speed being less important. Goleman suggests that technology has hampered our ability to pay attention, and that this might stunt our development in more ways than one.

Fuelling a short attention span with technology can cause collateral damage. People who respond to foreign or uncomfortable situations by burying themselves in phones and tablets don’t learn anything new. Picture a neanderthal who responded to a sabre-tooth tiger’s pounce by pulling out his iPhone to see if anybody was taking an interest in his relationship status. Other neanderthals would take an interest all right, when they asked his cave-girlfriend why she hitched someone stupid enough to check his phone in front of a sabre-tooth tiger.

Goleman’s research argues that children’s reliance on technological gizmos causes a “mental blurriness,” which wrecks the ability to adapt to new situations or to create a rapport with teachers. Learning is, by nature, a social activity. Lacking the proper emotional or social skills to connect with one’s surroundings and teachers undermines the purpose of technologies designed to make learning more convenient. It also just makes you more annoying to deal with.

“When you’re speaking face to face with someone,” Luk says, “studies show that about 30 to 40 per cent of that conversation will be about yourself. Whereas about 80 per cent of the content people publish on social media is about themselves.”

By now you’re probably thinking, “Screw off, why are you preaching to me like some luddite?” Fine, technology is not going anywhere. People love their phones. They give us something to read while we poo at work.

“Technology in itself is not a bad thing,” Luk says. “Your relationship with it can be healthy or unhealthy. It’s unrealistic to tell people to not use technology; it’s more about developing a healthy relationship. When you feel stressed, is technology something you go to to suppress feelings of anger and stress? Do you actually talk to people about it or do you just throw it up on your social media site? I want to emphasize that technology is not bad, but if it’s the only way you feel that can connect to the world there is a problem.”

Is technology the culprit or only the enabler of shortened attention spans? According to Penny Pexman, a professor from the U of C’s psychology department, staying away from the line between incorporation and addiction is the best way to approach smartphone technology:

“Smartphones are new distractions, but they can also be learning tools. Maybe the key question is, are you controlling your smartphone or is your smartphone controlling you? If you can feel your phone drawing you away from lectures or labs, then make some efforts to control your use; for instance, put your phone away when you get into class. In general, I think people are starting to realize that we need to manage our environments better so that we don’t have access to all information and devices all the time. Attention is definitely a limited resource, and no matter how good you think you are at multi-tasking, you will do better if you limit the number of things you are trying to pay attention to.”

The good news, then, is that high-speed and accessible mobile Internet might not actually be breaking our minds. The bad news is that our minds might be broken to begin with. Permanently.

“I think it’s important to recognize that all humans have a limited supply of attention, and there isn’t much evidence that we can change that with brain games or training or stimulants. You may need to change some habits or your surroundings in order to really be able to give difficult tasks the attention they need,” Pexman notes.

I asked Glen Bodner, another U of C psychology professor whose work focuses on memory and cognition, to chime in.

“I am not sure whether off-task behaviours in class are more frequent now or are just more obvious now than in the past. Technology may be dictating how we spend our time off-task rather than how often we are off-task,” Bodner writes. “It’s also possible that our new off-task gizmos make engaging in off-task activity more reinforcing, which might increase their use.”

Pexman added that she “hasn’t seen students become more fidgety and distractible over the years. Certainly they have different distractions now than 20 years ago, but the challenge to stay focused in lectures hasn’t changed. Even before smartphones students had lots of distractions in lectures, they could chat with classmates, daydream, make to-do lists and doodle in their notebooks.”

The caveman, sabre-tooth tiger and phone analogy was unrealistic. Not because cavemen don’t have phones, but because if any of them had to worry about tigers they would never catch enough slack to wander off into their cyberspace temple to the self. If you’ve ever seen Predator, Schwarzenegger was too busy being run down like a dog to post a status update about the space monster trying to collect his skull for its skull collection. This is what life was actually like in prehistoric times. Technology might be an unenlightened, junk food-esque fix for modernity’s sedentary lifestyle, but that does not necessarily make it the root of our attention problems. And according to Bodner, that root is still unclear.

“There has been an explosion of research of late on mind wandering which shows that our minds spend a surprisingly large portion of time wandering rather than being on task. Whether this portion is on the rise still needs to be studied longitudinally.”

For those of you too ADHD to read about ADHD, it’s a condition characterized by an inability to focus on and complete tasks. There are various theories regarding the cultural and anthropological roots of this condition. A bestselling book ADD: A Different Perception by Thom Hartmann, a psychotherapist, describes a hunter versus farmer hypothesis that gained traction in recent years after researchers uncovered evidence that ADHD is linked to altered brain production of dopamine — a neurochemical that regulates concentration, mood and energy. The fact that this mutation is heritable suggests ADHD’s chemical imbalance might have functioned advantageously once, and likely still can in certain situations that require a state known as hyperfocus.

Hyperfocus refers to a state of powerful immersion in the moment. Of course, it can’t be maintained very long, but hyperfocus can catapult the person experiencing it into a seemingly altered reality. This manifests in sports, when professional athletes talk about being “in the zone,” a place where time dilates and the world rappels away from them. It’s too bad they aren’t better wordsmiths, because athletes understand hyperfocus better than anyone and still always miss the chance for an eloquent description during their mumbly post-game interviews.

Hyperfocus also manifests in the use of powerful drugs, such as overdoses of amphetamines, which are used to control ADHD, or cocaine, which is used to scream at strangers from across the bar at Cowboys.

The evolutionary purpose of hyperfocus boils down to survival — hunting, killing, running from bears. The next time you’re on an airplane and the person in front of you asks you to stop kicking their seat, take it as a compliment. You are better-geared for combative living — your inability to sit still means that you are a machine of untapped primal savagery. They are the farmer. You are the hunter.

Unfortunately, we live in a world that rarely rewards hyperfocus or the adrenaline-addicted, fidgety individuals who can summon it. Without enough of cathartic intensity as a counterbalance, emotional factors like stress, depression and feelings of hopelessness can dampen one’s ability to concentrate. The only thing worse than chomping through heaps of art history books is doing it with hard science majors in your family slinging snide questions about your future.

Many students work through endless assignments with little hope of financial success in their field of study. Pexman points out that academic work is particularly draining.

“A lot of what we have to do as professors or students involves really hard mental effort, and we’re not going to do our best work if we’re devoting less than 100 per cent attention to the task.”

A lack of motivation often contributes to the “what the fuck is this all for?” question, which can boomerang around to knock away inspiration and dedication. Mental health problems feed into each other — people become stressed and depressed because they can’t concentrate, and feel like they’re going to fail at everything. And when they can’t concentrate, they might feel like they’re going to fail at everything, becoming stressed and depressed. Luk argues that stress is a critical component of ADHD because of this self-destructive loop.

“It’s a vicious circle. Say you can’t sleep. You go to bed, your mind races and races. The more you think about the fact that you can’t sleep, the more you feel awake. Western culture perpetuates a normalization of unhealthy levels of stress. People want to feel busy all the time. They don’t feel comfortable with themselves, like they have time or a purpose.”

While the link between mood and concentration-based mental health disorders is not entirely understood, they correlate with one another to a degree. This link can be frustrating to sufferers when the domino effect kicks in, but it does mean that the treatment options overlap.

One option is to grow up. No, I’m not mocking you. Getting older, accumulating experiences and transitioning from school to work hones the mind. Meg Jay, a clinical psychologist mentions in her book, The Defining Decade: Why Your Twenties Matter, that an overstimulated amygdala, a portion of the brain thought to regulate fear, can limit one’s ability to perform intellectually. When teenagers and twentysomethings enter new situations, they often have such limited experience that fear takes over and compromises their higher functions, overclocking the brain into an alert pattern with a death grip. The solution? Beat your fight-or-flight response into submission with new experiences and challenges. As one’s life goals become clearer, their amygdala becomes less hyperstimulated and their sense of aimlessness will start to fade. Improved focus will follow. Worrying that one does not have the skills to juggle life the way successful adults do is pointless because those adults have spent years and years developing coping and self-focusing techniques, likely after repeated failures. So get out there and start failing.

“But wait,” you’re thinking, “I need to learn to focus now, so that I can get through school and get on a career track first.” Well, you’re right — you do need to start now. There are many methods for training oneself to focus, as well as for treating attention problems. One of the most popular and controversial forms of therapy is medication.

ADHD remains a debated topic partly because a medical diagnosis entails amphetamine prescription, which has proven efficacious but presents poorly understood long-term effects and the potential for addiction. Luk doesn’t see a problem with stimulants, but warns against relying on them as a crutch.

“If used properly under supervision of a medical professional, go ahead. If [stimulants] are used correctly they have benefits. These medications can give you the energy to make changes, but you shouldn’t use them to continue living an unhealthy lifestyle. Think about harm reduction for high blood pressure, asthma, any type of chronic illness. These [medications] are rarely designed to cure illness. Stimulant treatment is just that — harm reduction. It must be combined with other methods.”

The popularity of amphetamines for studying highlights the sensitive nature of characterizing learning disabilities. If we diagnosed ADHD based off of behaviour alone, half of the students on this campus would be gobbling down amphetamine salts the way sweaty, hyperfocused athletes chug Gatorade. How many students are neurologically impaired, and how many of them just want an easy fix? There are no systems in place right now to scrutinize the credibility of ADHD for the majority of the population.

Another way to deal with attention lapses can be as simple as choosing how to take a break. Spending 10 minutes to walk around outside, rather than checking out social media, can benefit both the body and mind. Bodner and Pexman’s advice is as simple as unplugging completely — log off your email, avoid your Facebook, put your phone somewhere far away and get something hot to drink if you need it.

Taking smart breaks is really just part of a bigger picture: a healthy lifestyle. I don’t want to get L. Ron Hubbard on you all, but living healthy -— even if it doesn’t seem like you have the time — will make you a more efficient and productive student when you have to buckle down. Drink five glasses of water a day and get at least 30 minutes of cardio three times a week. In moderation, take supplements that promote the controlled release of dopamine, like ginseng, green tea, reishi mushroom extract, omega three oils, vitamin D pills (winter is coming). Get enough sleep. The necessary amount varies per person between 6–9 hours, and make sure your electronic devices are stored away when you tuck in. Finding ways to calm your mind, whether through creative outlets or through yoga and meditation is essential. I’d also tell you to eat more green vegetables and less red meat and carbs . . . but fuck that, beef is delicious.

One of Luk’s areas of interest is the concept of mindfulness, which he describes as a “piece of meditation” or “attention allocation training.” The U of C Health and Wellness Centre offers mindfulness and meditation training courses, many of which are free for students. According to practitioners of mindfulness, willpower is a muscle, and every redirection of your focus is a weightlifting repetition. Mindfulness rings like a hokey new-age concept, but it’s really just the practice of deliberately focusing your attention on a task or emptying your mind, rather than churning through amidst a sea of distractions. The meditative element comes from acknowledging those distractions and making a conscious choice to push them away. Forcibly ignoring the latest episode of your favourite Netflix series seems like a daunting task at first, but keep at it and it will eventually become a habit that yields positive results. At least, that’s what the adults keep telling me.