Stick ‘em with the pointy end

By Tobias Ma, October 16 2014 —

You can’t see your opponent’s face. A threaded wire mesh covers his head in a dome, leaving an expressionless visage. No tells found in a furrowed brow, an off-beat blink or grimace. Only the rhythm of his feet, sliding back and forth, and the twist in his torso’s centre line betray when the dancing sprig of steel in his hand may come snapping up at you.

Foil

John St.George is a second-year chemistry major who fences competitively with Calgary’s Epic Fencing Club, having competed provincially and nationally this year. He is also the president and a coach at the university’s fencing club. St.George looks the part of a swordsman — tall and thin with lanky grace. His movements emanate a catlike langor, long limbs bobbing rhythmically when searching for openings and feinting. Careful steps explode into flurries when he backpedals to escape an attack or lunge forward, but for much of the bout his presence implies the masked energy of a coiled spring.

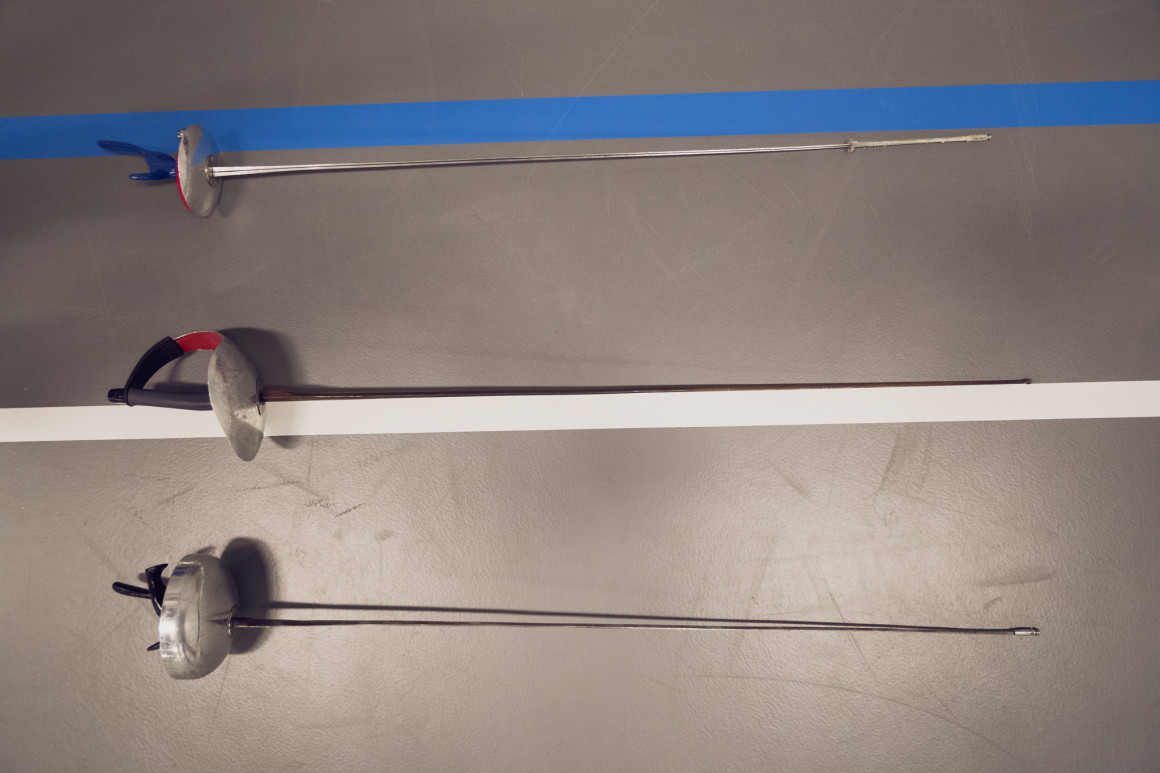

St.George fences with a sword called a foil, the lightest of the three weapons. The other two weapons are called epee and sabre. Each sword follows unique rules.

In foil, fencers can only score with the point of the sword. Slashing attacks with the edge of the blade don’t count. The torso is the only valid target. Of the three swords, foil is the lightest. Epee is the heaviest and longest, and although epeeists can only score with the tip as well, the entire body is a target. Sabreurs can attack the torso, arms and head, but not the legs. Sabre attacks can be made with the edge of the blade.

Sabre and foil are governed by a scoring rule called priority, which determines who gets the point if both fencers hit each other simultaneously. Priority goes to whichever fencer initiated the attack by threatening an opponent’s target with an extended arm. The fencer with priority has a brief window to hit even if he or she is struck during their lunge. If the attack misses or the defending fencer parries (blocks), initiative shifts to the defender, who takes the offensive. The priority rule encourages sabreurs and foilists to fight aggressively while discouraging wild flailing. Epee has no priority rule, so the first player to strike gets the point. All three swords emphasize different physical and mental attributes.

“A foil was handed to me by my coach when I was 13. I stuck with it. Epee was too boring, and sabre was too chaotic,” St.George says.

“What distinguishes foil from the other swords?”

“Balance. There’s priority, which is in sabre. But there’s also point control, which is in epee. Well,” he mutters to himself, “I guess you don’t need point control in epee because you can hit anywhere.”

Fencers enjoy sneaking in jabs at whichever swords they don’t use.

“What are some of the qualities that make an exceptional foilist?”

“Perfect technique. But you also have to be patient. You have to play your opponent. At a certain skill level, fencers are more or less on an equal physical playing field. They can hit a target accurately, they can move back and forth well. From that point on it’s a mental game. You need to manipulate them, as opposed to just trying to rush through and stab.”

“And how is this accomplished?”

St.George shrugs slyly, perhaps reluctant to publicize his trade secrets. “You can change your pace, give them openings, draw them into something. By giving someone an opening, you know roughly what they’re going to do, what options they have. If you can guess how they’re going to react, you can use that against them.”

The light weight and limited target area in foil make for a balanced pace as compared to the maneuvering of an epee match or the charging of a sabre duel. Lengthy exchanges are more common in foil than the other swords due to the difficulty of striking a skilled defender. Many foilists favour high-risk, defensive strategies, which resemble a kind of combative tennis. The first time I fenced St.George, I rushed him at every opportunity, battering his guard. He backed away, parrying cautiously until I grew frustrated enough to leave gaps.

Choice of sword reflects personality.

“Sabreurs are, well, loud,” St.George muses. “Epeeists tend to be more reserved. Foilists, as you might expect, is a mix between the two. [People from] each weapon have nuances.”

This makes sense, as sabreurs favour aggression, epeeists play the waiting game and foilists balance offence and defence.

Many fencers are academic, methodical people. The sport has a psychological metagame which requires deep focus and the ability to dissect weaknesses in your opponent. This could be why fencing attracts the occasional sociopath, egomaniac or nihilistic weirdo.

“I enjoy fencing because it’s both physical and mental. Most sports emphasize the mind over the body or vice versa. I find fencing encompasses both more than the others. It’s very satisfying to be able to manipulate your opponent just right. Have them thinking that they’ve set you up and then catching them — like having a bug fly into your web.”

Across the room his girlfriend gives us a nervous look.

St.George is not a sociopath, of course. The attitude which he displays on the piste, the strip that fencers must stay on during a bout, suggests that he is more interested in mastery over himself than others. Like all of the coaches at the University of Calgary’s Fencing Club, he is a volunteer. A group of experienced and gregarious epeeists comprise the club’s core. The club meets Wednesday evenings at 6:30 p.m. in the Gold Gym and bouts informally on Sunday afternoons, with an atmosphere geared towards socializing and learning.

Epee

The masked warrior squaring off with me is named Kali Sayers. She’s a first-year engineering major and apparently the top female epeeist in Alberta, although in her own words, “that’s not saying much.” Sayers is of average height and svelte, with close-cropped hair. I’ve watched her demolish the men at our club before, jabbing bruises into their ribs and arms before waving them off with a disarming smile.

I don’t fence epee, but my dumb brain believes that brutish sabre tactics will take an epeeist by surprise. The gimmick works initially, but Sayers is too used to aggression, having long ago learned to channel her own anger into the patience required for epee. She has been practicing for five years, and was drawn into competitive epee through modern pentathlon. At this year’s youth Olympics she won the fencing event of pentathlon, securing 20 of her 23 bouts.

“I have a physical edge over lots of female fencers because of my endurance. This was actually a disadvantage at the start, because I was used to plowing through people. My coaches said I fenced a bit like a bull. I’ve worked on timing and precision to be more delicate since.”

This information would have been helpful during our match. During one of the bout’s final points, Sayers lunges at me with a ferocious flèche, a flying attack often used to strike the head or throat. Backpedalling, I bat her aside and withdraw my arm to poke her in the stomach, but she twists away and stabs me in the face, a blow that would have gone through my eye had we been using live steel.

“Patience is important,” she cheerfully tells me afterwards. We are sitting in the dressing room with her mother. “In epee, make a mistake and you lose the point. Without priority, you can’t win on actions. Everything you do must ensure that you hit and that the other person does not.”

“You draw your opponents in,” I say.

“Yeah, you want to be in control, but you want your opponent to attack first. Get control through distance. You don’t want to attack first — you want to force them to. Time your footwork and scare them into doing what you want them to do. Capitalize on that. Predict what your opponent will do based on previous reactions. You can get a hand of people through strategic testing. Make a feint, and see which parry they perform. Some people have favourite parries, which means you will know which way to disengage [removing your own blade from theirs]. Some people are prone to hopping back when threatened. Some people will hop back and step forward. In that case, you can keep attacking because you know they’ll come forward into your sword without thinking.”

The chess game running under the hood of an epee match is what keeps Sayers coming back.

“It’s always different. People learn new things, change their styles. You have to keep up with them. If you figure out what someone is doing in a 15-point match, but once they figure out that you’ve figured out what they’re doing, they’ll switch it up. It’s constant, constant thinking.”

When I point out that a great way to induce an opponent to attack is by insulting them, Sayers laughs and says,

“Yes, you can look at how they act off the piste. Honestly, you can piss people off and they’ll make stupid attacks. There are also people who don’t like to attack, so if you can get ahead in points, you can take advantage of the time [limit] factor. Stand back, wait and force them to attack. They won’t be as good at that.”

It’s hard to imagine Sayers as the evil countess, taunting her opponents into a rage. But she’s competitive, running on the U of C’s track team in addition to her pentathlon commitments.

“One of my strengths is aggression.”

“Definitely aggression,” her mother adds.

“Mommy, be quiet!” she laughs. “I know I’m [physically] strong, that if it comes down to a wrestling match on parries, I can probably outdo most female

fencers there..”

“Is the situation different when you fence male fencers?” I ask.

“Male fencers approach me more confidently. Even against each other, guys will attack more often,” she grins. “Female fencing is often about counter-attacking and waiting. I think that because comparatively there are fewer women in fencing, we are more used to facing men. So women are almost trained to be more passive, to wait, to find ways to counter-attack, because we’re not as strong and often not as fast. So men will push into me, and I’m okay with backing up, as long as I have a plan and am not just running away. But I don’t mind fencing the guys. It’s a challenge, but I can beat some of them.” Two hundred years ago, Sayers would have been banned from fencing clubs because of her sex. But Modern Pentathlon was developed using the (questionable) logic that a captured soldier would need to run, swim, ride, sword-fight and shoot his way through enemy lines to escape. Sayers has come closer to the ideal of the chivalrous army officer than many men will.

Sabre

Sabre allows points by striking with the edge of the blade. However, sabre attacks are cuts, not slashes. Wild, unrestrained swings generate unnecessary force at the expense of precision and leave the forearms exposed to counterattacks. Although fencing blades are light and flexible enough to whip around an opponent’s guard, defending oneself with a sabre illuminates the messiness of actual swordfighting. Parrying is difficult, as use of the edge allows a new dimension of attacks. Footwork is essential to sabre, making it the fastest and most taxing of the three swords. Russian fencing masters have a saying: “the paws feed the wolf” — sabreurs will chase each other around to control the distance of the fight, instead of manipulating the other fencer’s blade.

Brian Chan is an engineering graduate and the U of C’s fencing club’s informal sabre coach. He views himself as an amateur but has instincts and speed.

“I used to do taekwondo,” Chan says. He was a competitor who has been ranked first in his division. “Fencing is a recreational experience for me. Sabre is more reaction-based — it favours fast-twitch reflexes. It’s aggressive, which reminded me of martial arts. I started at foil, because almost everybody does, but the progression was a clear choice. Epee is too slow, more of a defensive weapon. Not my style.”

You’re only as fast as your opponent, and Chan is quick. Everytime I fence him, my headspace shifts. At the referee’s signal we fly at each other. When two fencers hit each other without either gaining clear priority, which often happens in sabre, someone will mix things up by inducing their opponent to attack along a predictable line. Then, they will escape or deflect the attack and hit their opponent during recovery.

Chan is tall and agile. He knows that I favour direct attacks and long lunges, so he leans away and cuts at my wrist if I miss.

“I’ve trained over the years to strike to the wrist. It’s beneficial to do something different, since so many sabreurs are aggressive.”

Sabre gives you no time to scheme. You cannot bob on your toes and plot complex motions. The other fencer dashes at you hard out of the gates and you have no idea which way their attack will come from. Having a plan is only as useful as your ability to change it.

“What do you love about sabre fencing?” I ask.

“Here’s an example: you go for an attack, you miss. And then you automatically perform the parry and the riposte. Everything happens on it’s own. You don’t set up like the other weapons, you just do it all on muscle memory. Then you figure out what happened after. It’s a great feeling.”

Trained instincts can save sabreurs from critical mistakes. Although it is the most anaerobic of the three swords, it can also be the most relaxing. One can fence with a blank mind and still experience success.

Several days later, I’m hanging out with my coach, Elya Perritt of Gladiators Fencing. Perritt has coached since 1992 and teaches all three weapons. Perritt is adamant that anyone can learn.

“In terms of neurons everyone’s reaction speeds are similar. Line any two people up and have them press a button when a light comes on. The results will be close. Fencing is just about recognizing situations and knowing how to respond to them. That comes with experience.”

Technique and training outweigh athleticism.

“Is there an age fencers peak out at?” I ask.

“There are people who are getting medals at the world championships in their late 30s. The older you, are the more reference you have, the more situations you’ve seen. Older athletes can also increase their muscle size, make themselves more explosive and efficient.”

“How would you suggest that beginners pick a sword?”

“Put the weapon in the student’s hand and see how they do. People perform better with a weapon they have chosen and enjoy. To pick on size or reach is . . . well,” he harumphs. “There have been really good epee fencers that were short. If their coach had prejudiced them against that weapon because they were short, the world might never have seen a medalist.”

“Do you think of fencing as a dying art?”

“No. Fencing’s popularity in Canada is increasing.” Fencing’s international popularity has spiked now that Europeans are no longer unstoppable. Asian and South American countries have seen success at recent Olympics.

Epee is a derivative of the French word for sword. There is a vestigial incision which runs along an epee’s blade called a blood groove. This indentation allowed blood to spill out freely when piercing flesh, rather than clot. Perritt dislikes the term, believing that it casts a violent image on the sport. But the groove is a reminder of fencing’s roots.

Well into the 1800’s, swords were both fashion symbols and tools for personal defence. Standards of masculine conduct, combined with the availability of arms led to an explosion of the practice known as duelling. Duelling is an odd concept. Picture hordes of Friday night bros, drinking and riding the C-train, ready for an evening of wheelin’ the ladies. Except rather than Air Jordans or Armani shirts, they carry swords and the sanction of their peers to skewer each other at perceived threats to their honour.

We tend to think of people who fly off the handle and punch others as silly, or at least inarticulate, but fisticuffs are spur-of-the-moment affairs. By contrast, duels were pre-arranged, involved lethal weapons and took place with cultural support. In many parts of Europe and America, a man who failed to challenge someone who had wronged him was looked down upon. Many thinkers were divided over how to question the value of duelling without appearing like cowards.

By The Sword, a treatise on the history of fencing by Richard Cohen, abounds with stories of duels involving accomplished individuals. Abraham Lincoln nearly fought a duel, but he separated himself and his much shorter opponent by placing them on isolated planks of wood, leaving the other man with no reach to strike him (and no choice but to come to an agreement). Renee Descartes, an avid fencer in his youth, nearly killed a man after the drunken intruder groped his female companion. Karl Marx was cut above his eye in a saber contest, the byproduct of many clashes between his bohemian drinking buddies and the soldiers who patronized their favourite tavern. George S. Patton almost won gold at the 1912 Olympic Pentathlon due to his skill with a broadsword, and Benito Mussolini would tell his wife that he was off to “get spaghetti” — his code phrase for duelling to avoid alarming their children.

Winston Churchill knew a thing or two about swords, but when confronted by several swordsmen during his years as a soldier he opted to shoot them. Imagine what might have happened to England several decades later, had he drawn his sabre and charged instead.

I asked each of the three fencers interviewed about what they found beautiful in their chosen weapon. The foilist likes playing with his food, the epeeist wants a challenge and the sabreur seeks the zen moment. Hundreds of years ago, all three would have been farmers, merchants or tradespeople, ruled through fear inspired by the weapons of nobility. Today, anybody can fence without condemnation of their class or gender, and without being forced into pointless duels over trivial disagreements.

The sport’s meaning rests entirely on the fencer, whether they are a history buff, an Errol Flynn fan or seeking to improve their cardiovascular health. Surely there is beauty in that as well.