The Contemporary Dilemma: Decolonizing your bookshelf

By Aymen Sherwani, September 22 2021—

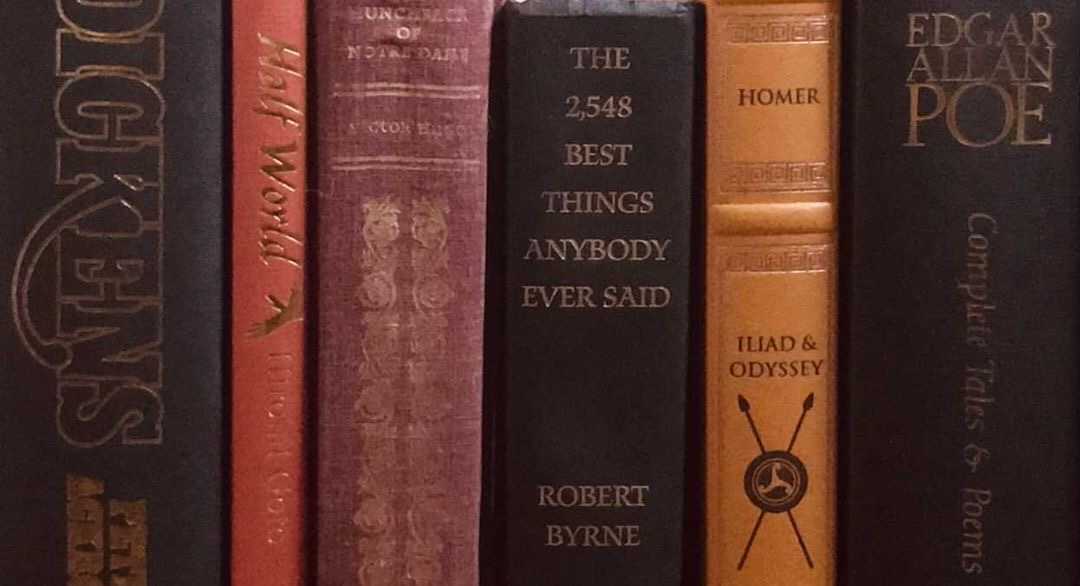

If you pride yourself on being a reader, take the time to examine the names that have found a place on your bookshelf. There are probably a lot of fun and quirky young adult novels and, of course, “the classics” that everyone tells you to read at least once in your life — but have you ever stopped to consider what exactly classifies as classical literature? I’ll give you a hint — oftentimes, it has nothing to do with when a work was published but, instead, everything to do with who published it, especially if they’re a white author.

Obviously then you’d ask ‘Well, what’s the problem with that if what I’m reading is good?’ Depth. Nuance. Lived experience that white voices will never understand. What if I told you that many authors of colour have equally thought-provoking works from around the same time periods, yet are passed over when discerning what constitutes literary canon?

While the problem of gatekeeping within the literature community continues to persist, what readers can do is make the effort to “decolonize” their bookshelves, and fill them with the voices of authors of colour that process stories and historical events through a deeper lens than that of a white observer. Below are a couple of my favourites.

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe (1958)

Achebe’s most famous work, Things Fall Apart, is seen as a response to Heart of Darkness (1899) by Joseph Conrad within which Conrad offers parallels between London as “the greatest town on earth” and Africa as places of darkness, where “savages” live, ultimately alluding to the benevolence of British colonialism. Achebe’s work counteracts Conrad’s earlier novel and instead is a heavy exploration of the Nigerian Ibo tribe’s customs and how they are impacted by European colonialism and the coercion of Christian missionaries.

The Nigerian novelist later went on to call for Heart of Darkness to be removed from canon classical literature due to its heavy reliance on racist imagery and notions that British colonialism may have been a good thing. Overall, Things Fall Apart is worth the read because it challenges the traditional narrative of African tribes needing European colonialism to “modernize” but, rather, how discriminatory and white-supremacist the notion of modernization is in itself.

Orientalism by Edward Said (1978)

Said focuses his commentary on the misconceptions of what is considered to be the “Orient,” ranging from Morocco to Japan, and how colonialism has led to the gross oversimplification and fetishization of such a diverse region. The Palestinian-American author explores how the term itself is contemptuous and has historically been used to position the inhabitants of that region as inferior to the West, further explaining our contemporary understanding of international politics.

As readers, it’s important to understand the racial nuances and implications that are proposed in Western literature and “Orientalism” by Edward Said has sought to challenge these assumptions. This was the book that made me realize that it didn’t matter that I grew up in Canada because my status as a visible minority creates preconceived assumptions about who I am, further affecting the way I am treated by complete strangers.

Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence by Doris Pilkington Garimara (1996)

Pilkington wrote Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence based on her own personal account, as an Indigenous-Australian, from when she was held at the Moore River Native Settlement internment camp due to her “half-caste” — or mixed-race — identity.

The book parallels her experiences, as well as those of her relatives, and focuses on the characters of Molly, her half-sister Daisy and their cousin Gracie who are taken to Moore River for schooling to become assimilated into white-Australian society and are part of the Stolen Generation of Indigenous children that are subject to the eugenics-based policies in Australia at the time. Readers should definitely consider this work as it is a raw account of the genocidal tactics used to suppress the Indigenous identity and also draws large parallels to Canada’s own dark history of residential schooling and our persisting legacy of colonialism.

There are thousands of strong and fearless men, women and children all over the world. These are the people that wake up, despite the atrocities they are facing, and push forward without looking back. These are the people that sacrifice everything so their families will have a better future. This is what The Contemporary Dilemma highlights. This column is part of our Voices section and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Gauntlet’s editorial board.