The University of Calgary’s LGBTQ History

By Jason Herring, August 29 2017 —

Photos by Mariah Wilson. Archive photos provided by Calgary Gay History Project

Calgary has a complicated history with the LGBTQ community and the University of Calgary is front and centre in much of that history. When the school opened in 1966, homosexuality was illegal in Canada. Even for decades after Canada decriminalized homosexuality, gay people were prosecuted by police for “gross indecency” and were not granted many of the same rights as straight people.

In the past, the U of C has been a place for progressive conversations about LGBTQ rights and has been home to activism and legal advocacy — but it has also suffered from incidents of discrimination.

Kevin Allen is the lead researcher for the Calgary Gay History Project. He regularly holds walking tours discussing gay history in Calgary, including one at and about the U of C. Allen took me on his tour of campus to show the Gauntlet some of the school’s rich history.

[hr gap=”30″]

Early Lecturers

The U of C played host to a number of controversial speakers in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, including members of the Black Panthers and counterculture icon Abbie Hoffman.

“The SU, back in the ‘60s, was very activism-oriented,” Allen said. “They weren’t the kind of corporate Students’ Union that we have today. They started bringing in very provocative speakers.”

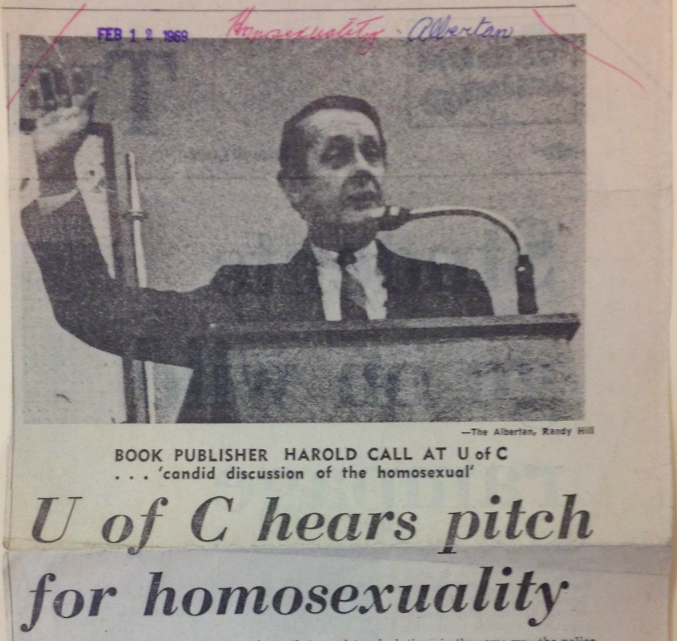

Among these guests was Harold Call, a founding member of the San Francisco Mattachine Society, one of the first gay-rights organizations in the United States. Call spoke about problems with how police forces in America approached homosexuality. In his lecture, he caused a stir when he noticed members of the Calgary Police in attendance.

“There were three undercover plainclothes police officers in the crowd who he outed and pointed out to the crowd and they kind of slunked away,” Allen added.

Another speaker was John Wolfenden, a British academic whose chaired a committee that recommended in 1957 that the U.K. government decriminalize homosexuality, which greatly influenced Canada’s choice to do the same. In his lecture, Wolfenden advocated for individual freedom, saying that though some might see homosexuality as immoral, it was not the government’s place to legislate morality.

“Universities are places of open-mindedness and challenging traditional thought and at a time when homosexuality was criminal in Canada, they were bringing in lecturers like this,” Allen said.

[hr gap=”30″]

Campus Media

The U of C’s three student-run media outlets — CJSW 90.9 F.M., NUTV and the Gauntlet — have all historically provided a platform for LGBTQ students. CJSW first aired a recurring queer radio program in 1990 called “Speak Sebastian.” In addition to discussion of LGBTQ topics and culture, the show regularly gave information and updates about AIDS, which was then becoming an epidemic for Calgary’s gay community. Soon afterwards, CJSW starting airing other LGBTQ radio shows, like “Dykes on Mikes” and “Freedom F.M.”

According to Allen, these shows were significant not only to the U of C and Calgary community, but also to LGBTQ people outside the city.

“CJSW’s signal was so strong, even back then, that it would reach a lot of people in rural Alberta,” he said. “That voice really reached out to a lot of isolated rural gays and saved their lives. They realized they weren’t alone.”

NUTV, the U of C’s on-campus television station, established itself as a safe space for LGBTQ students and contributed to the community’s art scene soon after its launch in 1983.

“NUTV, in part of its history, had queer staff, so back in the ‘80s they were doing video art work in some of the artist-run centres in the city,” Allen said. “They always had a good policy around the university and they accepted a lot of viewpoints and voices.”

A large part of the Gauntlet’s role in LGBTQ history was documenting developments on campus, as well as giving both writers and students a space for debate and organization through its opinions section and its classified advertisements. As Calgary Gay History Project researcher Nevena Ivanović writes on calgarygayhistory.com, the paper’s “uneven editorial tone and often flawed reporting” and “omissions of landmark moments in gay and lesbian activism of the 1970s” expose flaws in the newspaper’s past coverage of LGBTQ issues. However, Allen maintains that the Gauntlet was instrumental to the campus’s gay history.

“I can not overstate how important the Gauntlet is to Calgary’s queer history, because mainstream newspapers weren’t covering queer issues very much and student journalists were more interested in exploring those issues,” he said.

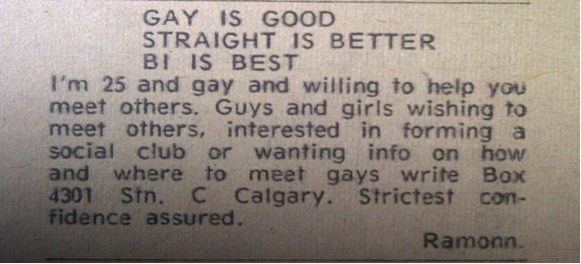

The first opinion piece published in the Gauntlet by an openly gay man was Rick Sullivan’s impassioned piece about gay liberation in 1972. Around this time, a number of anonymous classified advertisements appeared in the newspaper under the tagline “GAY IS GOOD,” providing information to those wanting to meet other LGBTQ people.

[hr gap=”30″]

On-Campus Organizations

Throughout almost all of the U of C’s history, a club has existed on campus for LGBTQ students and staff. Sullivan started the first, called the Gay Liberation Front, in 1972 in the midst of a movement started in New York City when protesters fought back against police performing a raid on the Stonewall Inn. The U of C group’s history, however, is not well-documented and may have become defunct less than a year later.

The Gay Academic Union found more long-term success on campus, forming in 1978. They served as an organizer for debates on LGBTQ issues on campus as well as provided support for students and staff. Allen explained that the organization, which fell in line with the gay equality movement, was significantly less radical than that of the Gay Liberation Front.

“The liberation movement came out of a bigger civil rights movement. It was very radical. It was trying to deconstruct society. A lot of gay liberationists wanted no age of consent, they wanted freedom on a lot of different levels,” Allen said. “Gay liberation was for rejecting society, while the equality movement wanted to be embraced by society, so there was a tension between those two groups.”

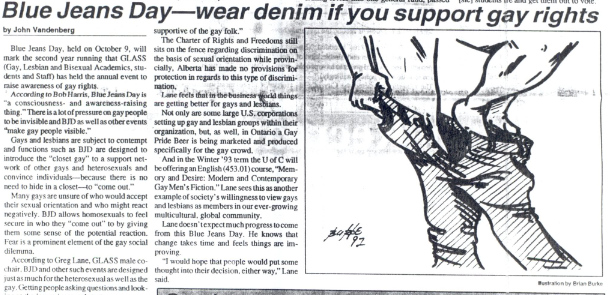

The Gay Academic Union gave way to Gay and Lesbian Academic Students and Staff (GLASS). The group engaged in advocacy in the late ‘80s and ‘90s, largely during the peak of the AIDS crisis. Allen was a member of the club during his undergraduate degree.

“I feel like a solider from those days,” he said. “It was a cultural war in the early ‘90s, which was when AIDS were the worst in Calgary. Calgary was the hardest hit place in Alberta. That made people militant — a lot of gays who had been in the closet until then had been dragged out and made militant because they were dying. Stakes couldn’t have been higher.”

One of Allen’s best memories of his time at GLASS was the Blue Jeans Day, whose concept was simple — wear blue jeans if you support gay rights.

“Ninety per cent of the university community was wearing blue jeans already,” Allen said “The engineers, I remember, would show up in khakis or dress pants for that, even though they wore blue jeans every other day of the year.”

Today, the campus is home to the Queers on Campus club, who focus on providing “education, political action and social events” to members of the U of C community. A number of LGBTQ events in Calgary also originated on campus, including the Coming Out Monologues in 2009 and the Gender Bender, which has taken place since the ‘80s.

[hr gap=”30″]

Discrimination

GLASS often faced harassment from homophobic groups. Their offices were in the MacKimmie Tower instead of with other clubs in MacHall because of a higher security presence in MacKimmie. Notably, a poster was left on the GLASS door in 1992, advertising “fag and lesbian bashing” at the location of an upcoming Pride parade.

“There was a bit of a hullabaloo and the police were called to investigate,” Allen said. “That’s an example of the kind of low-level harassment gay people had to put up with back then on campus.”

Police responded to the poster but failed to find its author. The Pride parade occurred without incident.

The Rock, outside MacKimmie Tower, was often used by GLASS to advertise events, but their messages were often quickly painted over by opposing students — notably engineers, according to Allen.

“We had an ongoing war at that time with the engineers, because they were notoriously misogynistic and homophobic at the time,” Allen said. “When we were here, we would paint our events, and they would immediately be painted over, this vandalism for our own promotions.”

In fact, the response to GLASS’s messages on the Rock escalated beyond paint.

“At one point, the engineers — the rock used to be much bigger than it is now — the engineers blew it up,” Allen said. “The concert hall wasn’t here, it was just MacHall, but all the windows in MacHall were shattered by the explosion. The university administration was very upset.”

This, along with a misogynistic and homophobic skit performed by engineering students during orientation week in 1990, prompted the U of C to require all engineering students to complete diversity training in their first and last years at the school.

A frequent on-campus “cruising spot” — a public place where gay men go to have sexual encounters — was the second-floor washrooms in the southeast corner of the Administration building.

“On the U of C campus, that was the place to go,” Allen explained. “The police morality squad liked to crack down on that kind of, in their eyes, immoral activity. Gross indecency was the charge homosexuals were given. [Both on- and off-campus,] they would set up hidden cameras, they would set up stings with young handsome police officers.”

The Calgary Police also tracked LGBTQ student activists at Calgary post-secondary institutions throughout the ‘70s, asking the schools for records on certain students — though the U of C refused to provide them.

For much of their history, the Calgary Police have had an antagonistic relationship with LGBTQ people. A notable instance is Everett Klippert, a Calgary bus driver who was arrested and sentenced to four years in prison in 1960 for having sex with men. After serving his sentence, he was arrested again in the Northwest Territories and sentenced to three more years on the grounds that he was a dangerous offender. The ruling was appealed to the Supreme Court, who recommended Klippert be sentenced to life in prison. In response to the ruling, then-Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau passed a bill to decriminalize homosexuality.

The Calgary LGBTQ community’s relationship with the police remains fractured today, with Calgary Pride recently announcing that uniformed officers will not be allowed to march in this year’s parade.

[hr gap=”30″]

Today

The U of C’s LGBTQ history continues to be written. In 2010, the Q Centre launched on campus and soon after moved into its home on the second floor of MacHall. The school’s first gender-neutral washrooms opened in the same building in 2014. As well, U of C faculty and the school’s Students’ Union both now walk in the city’s Pride parade yearly.

While Queers on Campus co-chair Margaret Patterson stresses that everyone has a different experience, they’ve personally had a positive experience at the U of C. They say the Q Centre in particular provides many resources to LGBTQ students.

“Last year the Q Centre hosted discussion nights about mental health and masculinity in the community,” Patterson said. “They also provide peer support, they provide a braver space and they’ve done educational panels.”

Patterson says that more gender-neutral washrooms are needed at the U of C. They add that the classroom experience could be improved by having professors complete inclusivity training.

“Professors aren’t always equipped to deal with classroom discussions when they get out of hand,” they said. “I’ve been in some classes where it’s going well, but then a student says something that isn’t that inclusive and the prof doesn’t know how to deal with it.”

Still, the campus has come a long way since the days where campus LGBTQ groups faced slurs posted to their doors and police set up stings on campus to prosecute gay men. With considerable resources and a large community on campus, the U of C has never been a better or safer place to be LGBTQ.