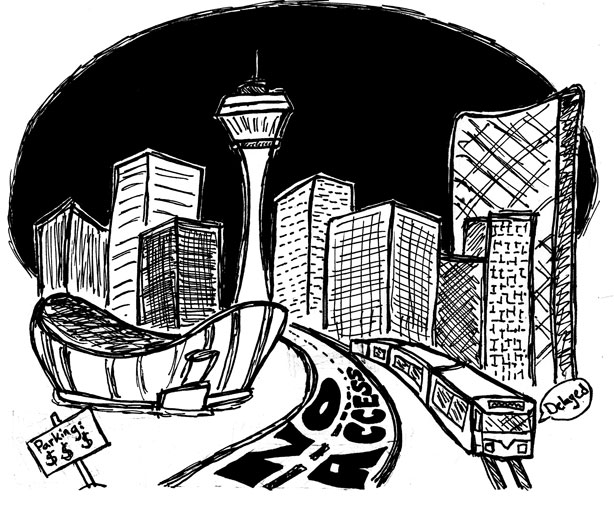

Average citizens left behind in Calgary’s rapid growth

Calgary is a nice place to live. There’s a burgeoning arts scene and the skyline is nicer than it used to be. Unemployment is low. We even have a fancy bridge to cross the river.

The problem isn’t what Calgary has. It’s that the city isn’t on offer for a large group of people.

Calgary is full of things to do and places to see — if you have a white collar job at an oil and gas company and can afford to purchase a condo. For the rest of us — students, families, service workers — Calgary offers up a lot of unasked-for gushing about being one of the wealthiest cities in Canada. Calgary may be wealthy, but not everyone who lives here benefits from all that money.

The rental market in Calgary is almost non-existent. The vacancy rate sits at just over two per cent. Secondary suites can’t get through city council. Rising rents and record growth mean students often live in illegal secondary suites that can have serious safety problems.

Even students who live on campus to avoid high rents and illegal secondary suites are being gouged. An increase of eight-and-a-half per cent was proposed for first-year residence in October, with an eventual five per cent increase approved by the Board of Governors in December. In the new residence buildings being built, the top floors come with an added price tag for the panoramic view of suburban Calgary.

Calgary has the highest monthly downtown parking rates of any city in Canada. When it comes to parking in North America, we’re second only to New York City. The cost of monthly parking in Calgary is approximately $473, according to commercial real estate brokers Cushman & Wakefield. This is almost double the national average of $251.

It’s possible to avoid parking by using public transit. Monthly transit passes are within $5 of other major Canadian cities. But there’s an issue with reliability.

We spend money on roads before public transit and expand our motorways before city councillors can even start talking about LRT expansion.

Calgary is a sprawling city connected by expressways. The cheapest housing is in suburban neighbourhoods, so workers are often forced into long commutes — unless they can drive. Having a car allows residents to easily access the majority of Calgary’s amenities. Those without cars are either left with a long time on transit or left behind.

Transit is mostly used by vulnerable populations with little political power. Students and service workers don’t have the clout to force transit expansions through city council in the same way that developers and homeowners associations can get support for new freeways.

There are entire neighbourhoods without access to public transit. Calgary does have an extensive pathway system, but it’s mostly used for recreational biking and walking instead of commuting.

Calgary’s transit use is lower than other Canadian cities. In Toronto, a little under 25 per cent of people use transit for their daily commute, according to Statistics Canada. In Calgary, only 17 per cent of commuters use transit. Calgarians won’t commute on public transit unless doing so is easy and convenient. As Calgary grows, our transit system needs to grow with it. We build new roads and traffic lights to connect new developments. We should be expanding our public transit services at the same time.

Calgarians without cars also experience a phenomenon known as food deserts, neighbourhoods where a lack of grocery stores mean that residents don’t have access to nutritious and affordable food. Inner-city neighbourhoods like Inglewood and Elbow Park are frequently home to trendy restaurants and specialty food stores, but lack grocery stores where residents can purchase basic necessities. People without access to a car like students and the elderly find it difficult to purchase food.

Because food deserts aren’t an issue for people who are middle class — those who usually have access to cars and finances that allow them to be more mobile — they don’t get a lot of attention as an accessibility issue. Basic necessities like food should be accessible to all Calgarians. This means designing communities around access to amenities like grocery stores instead of on the whims of developers.

The way we think about our cities is a product of how we live in them. Calgarians don’t naturally love cars, highways and detached suburban housing.

But we live in a city where that lifestyle is more accessible than one that promotes public transit and dense mixed-use housing. It’s unfair to promote biking and walking to work when doing so is dangerous and time consuming.

Infrastructure — basic physical and organizational structures — is what affects how we live. We can talk about the importance of locally grown food, walkable communities and dense housing until we’re blue in the face. But services in Calgary match the lofty dreams of urban planners, the city will remain as inaccessible as ever.

If the city wants more cars off the road, make sure there’s a reliable bus route that takes me to work. If you want people to eat healthier, build a grocery store near my house. If you want less poverty in the city, make sure I can find and afford a place to rent.

Calgarians can’t make choices to create a more livable city when there’s no infrastructure to support them.

Kate Jacobson, Gauntlet Editorial Board