Year One: The truth behind gender inequalities in university

By Anjali Choudhary, May 13 2021—

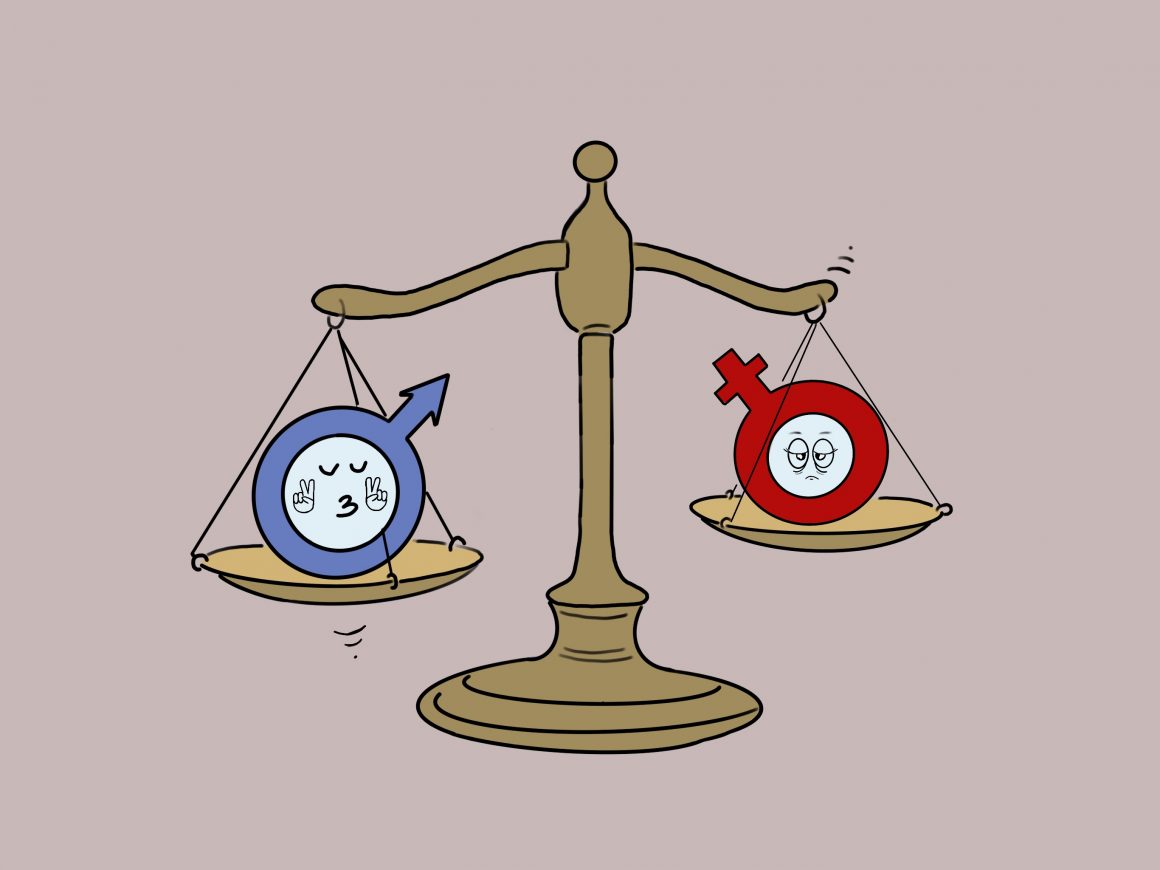

In America, there are more men named John running large companies than there are women in their entirety. If we were living in the 1900s, this statistic would not be nearly as groundbreaking. However, in an age of constant advocacy and large feminist movements, it is not only frustrating but downright mortifying for the country as a whole. The pushback of subtle anti-feminist movements within workplaces and higher education must be fought. Female representation in typically male-dominated fields, such as science, technology, math and engineering (STEM), is crucial to advance equal opportunities and encourage new generations of empowered women in all positions.

The pressure of choosing a supposed life-long career during the peak of your adolescence is an entirely unique and terrifying experience. However, the fear of entering a field simply because of your gender identity should never cross a student’s mind. Women deserve the guarantee of a safe work environment, void of inherent discrimination and biases. Why is it that the most highly praised individuals in the world — Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk and Bill Gates — are all men? And no, I do not want to hear the “they work harder than everyone else” mantra. This logic simply cannot apply in a world where women in Canada still earn 12 per cent less after graduation in comparison to their male counterparts.

While these harmful stereotypes are often seen in the workforce, they are also reinforced in the post-secondary environment — beginning from the first day of a student’s first year of their STEM-related degree. In an interview with the Gauntlet, a fourth-year undergraduate student, Vivian Davis, details her journey from previously studying engineering and computer science to ultimately transitioning to a humanities field at the University of Calgary. She spoke to her experience with the reality of gender discrepancies at the post-secondary level and how they informed her decision to leave STEM.

While recognizing the importance of gender diversity in STEM, this student noted that the age-old depiction of “male-dominated” fields continues to hold true today.

With women making up only 22 per cent of undergraduate engineering students in Canada, these stereotypes are consistently reinforced and upheld. This discrepancy of numbers is both intimidating and disheartening — especially for first-year students who have high aspirations in the STEM field. This mental barrier often translates into the workforce. Davis recalled being “swept up in this gender discrepancy” and “feeling very unmotivated to try.”

“It was clear that even if I did well in computer science I would be competing with 20 men for a seat in an internship, and I felt like I would never truly belong, regardless of my skill level,” said Davis.

Nobody should have to fight to death for their well-deserved place at the table simply because of factors out of their control. In fact, the presupposition of this should not even exist.

Post-secondary education is what many high school students strive for and often idealize. However, if the university fails to advocate for about 50 per cent of the province’s population, it is setting them up for failure before ever setting foot on campus. This pattern then continues into their first-year, discouraging women from pursuing their dream jobs simply because of a daunting and discriminatory education system. Simply choosing a field that has historically been male-dominated can be very frightening and act as a deterring factor for women choosing their career paths after high school.

A big fear factor for women beginning or deciding to continue a post-secondary education in a STEM-related field is the number of historical statistics surrounding gender inequalities. University is difficult on its own.

“The portrayal of STEM related fields can affect the thinking of a younger person more so than other age groups,” Davis adds.

“It’s easier to be a victim of imposter syndrome in post-secondary, and even more when you’re a clear minority in a large group. In my personal experience, I’ve found that professors at [the] University of Calgary are very willing to help you succeed and the student environment is very healthy, but looking at these fields as an outsider can be nerve-wrecking and can easily drive someone away from their interests,” she said.

She adds that, “stereotypes like ‘girls are bad at math’ and ‘girls tend to go into the humanities’ can shape one’s thinking from a young age and stop them from even considering a field in programs like engineering.”

No student, especially those just beginning their journey, needs the additional stress of wondering whether they will walk in the same path as their predecessors — whether they want to or not. To combat this, all individuals in the STEM field must face their internalized misogyny and bias and actively work towards creating a better future for women entering the field.

As a current or incoming first-year undergraduate student, the advocacy of the university is extremely important and motivating. It is absolutely vital for major institutions — especially those training new generations — to promote equality from the initial stages. Though it may seem like the bare minimum at times, the impact of the simplest of acts from institutions, such as the University of Calgary, will have vast influences beyond the campus grounds. The continual inequalities, despite decades of protest, show that it is large institutions that can act as effective catalysts for change. While not impossible, the battle will undoubtedly be far more difficult without their support.

Foremost, the conversation in academia regarding gender inequality needs to be more prominent. Actions definitely speak louder than words, but conversation must precede this in order for meaningful change to occur. Incoming first-year students need to be adequately prepared and informed when choosing the university of their choice, their programs and specific classes. This may be seen as a deterrent factor, but it will only serve to allow women to make an informed choice and feel further validated in their experiences. Pretending Canadian universities are perfect, equitable institutions will only lead to inaction. However, this conversation must lead to action tackling the systemic issues in the university.

Davis noted that in her opinion the university did “a good job of creating a welcoming environment” and “never felt like I was at a disadvantage due to my gender while studying in engineering or computer science.”

Although she feels “that the university has done a good job with promoting equality by hiring good professors and being intolerant of discrimination,” she believes “there is an extent to how much they can truly push gender equality at the post-secondary level.”

“It’s okay to feel like an outsider,” Davis said. “When you walk into that computer science class and see the entire lecture hall filled with men, hold on to your fascination with the subject and remember that you are cool. Keep that head up, you got this!” She adds that, “the only thing that keeps [her] going is that [she] knows [she’ll] get there and in the end this will be remembered as a small speed bump in [her] life journey. Plus, life would be too boring if it were so easy.”

Year One is a column about the first-year experience at the University of Calgary. This column is part of our Voices section and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Gauntlet’s editorial board.