Why does the federal government keep failing at amending Indigenous relations?

By Anjali Choudhary, November 17 2022—

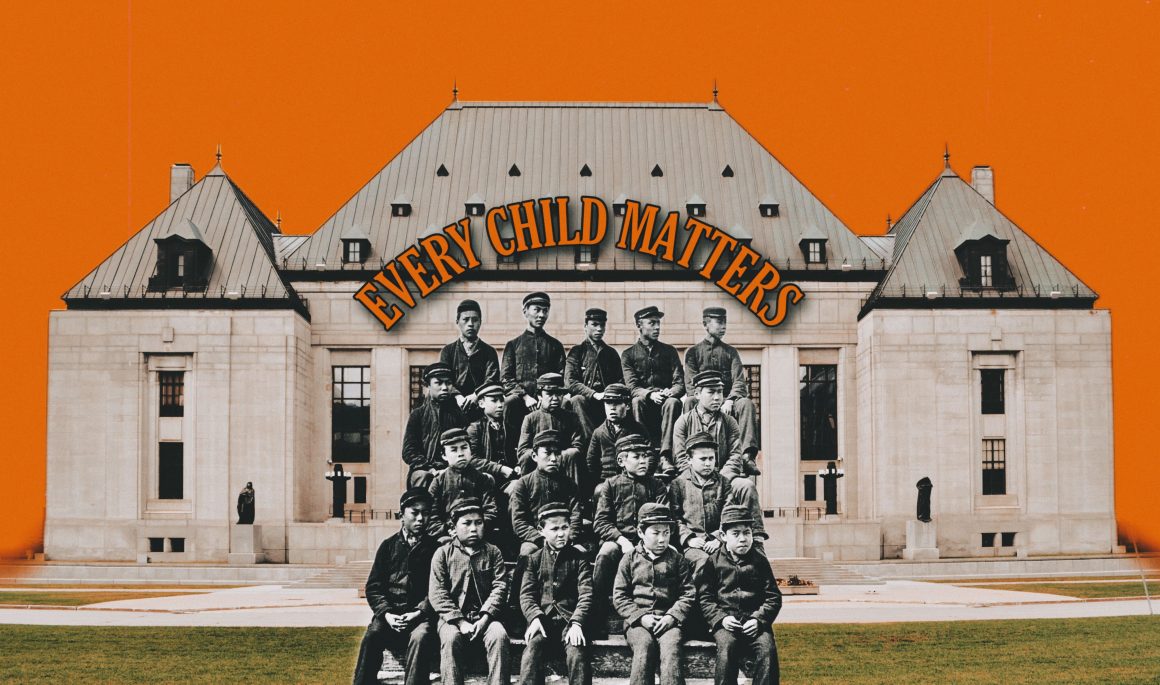

Earlier this year, after being criticized for unnecessarily drawing out a large legal battle, the federal government announced a landmark $40-billion deal to compensate Indigenous children harmed by the child-welfare system. Despite all the gloating and pride from the Liberal party, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) has now announced that the deal does not meet the standards that were initially agreed upon. This ruling followed another breaking case in which the Supreme Court of Canada refused to hear a group of residential school survivors’ case in obtaining sealed residential school documents. Some survivors claim that the government’s refusal to release the documents — which contain proof of abuse that occurred at St. Anne’s residential school — has lowered the level of compensation they received. Again, the Canadian government finds itself in the midst of a decade-long battle against those who they have been claiming to do everything to support.

There is an eerie and heartbreaking pattern in current reparation actions taken by the government. While it is true that no preceding government has provided such levels of compensation, the Liberals are continuing to be exposed for doing too little and putting up an enormous fight along the way. In the past few years, conversations around performativity have largely revolved around individual people — whether that be teenagers or celebrities limiting their activism to social media posts. However, it is far more important to consider whether the individuals who are paid to lead the country also limit themselves to performative allyship.

The Liberal Party platform claims “Over the last six years, we worked to reduce the number of Indigenous children in care and make sure Indigenous communities have the support they need to keep families together.”

However, Cindy Blackstock, executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, told The Star that the federal government has had years to comply and if they had done so, the total compensation would have involved “hundreds of millions” but not billions. This is further to the fact that in the past nine years, the government has only completed about 10 per cent of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action.

It is impossible to undermine the impact that the compensation will have on many families. However, how much should the government be praised when they were forced to take these actions after years of kicking and screaming? The resistance — both in the past and present in the case of the St. Anne survivors — speaks volumes to the true intentions coming from the House of Commons.

Stuck in the middle, however, are the Indigenous families that have been waiting years for compensation. While criticism of the government’s motives and deals is necessary, the precarious and precedential nature of the settlement cannot be understated. Because of this, the CHRT’s ruling is consequential on many different levels for the Indigenous community.

“It’s very frustrating that this legal wrangling is happening because now First Nations people are the ones who are having to wait yet again,” said Cindy Woodhouse, the Assembly of First Nations Manitoba regional chief in a statement to the CBC and Global News. “I don’t know when or if compensation will flow to these kids and families at this stage. We have come so, so close to compensation finally reaching our people. And today’s ruling is a significant, significant setback.”

Other Indigenous community members, however, also recognize the need for the CHRT decision in holding the federal government accountable.

“It appears that [the federal government] started to realize that there were so many victims hurt by Canada that they weren’t able to include all of the victims,” Blackstock told CTV News.

The rhetoric surrounding reconciliation often revolves around Canada’s previous injustices and dark colonial past. However, these two cases and many more have proven that not only are injustices against Indigenous communities still prominent, but governments and institutions are actively avoiding their responsibilities — even legally enforceable ones — in the reconciliation process. The onus remains with the federal Liberal Party to unseal documents, ensure every single individual that was harmed is adequately compensated, and put action behind their words without having courts and tribunals forcing them to do so.

This article is a part of our Voices section and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Gauntlet editorial board.