A mountain by any other name

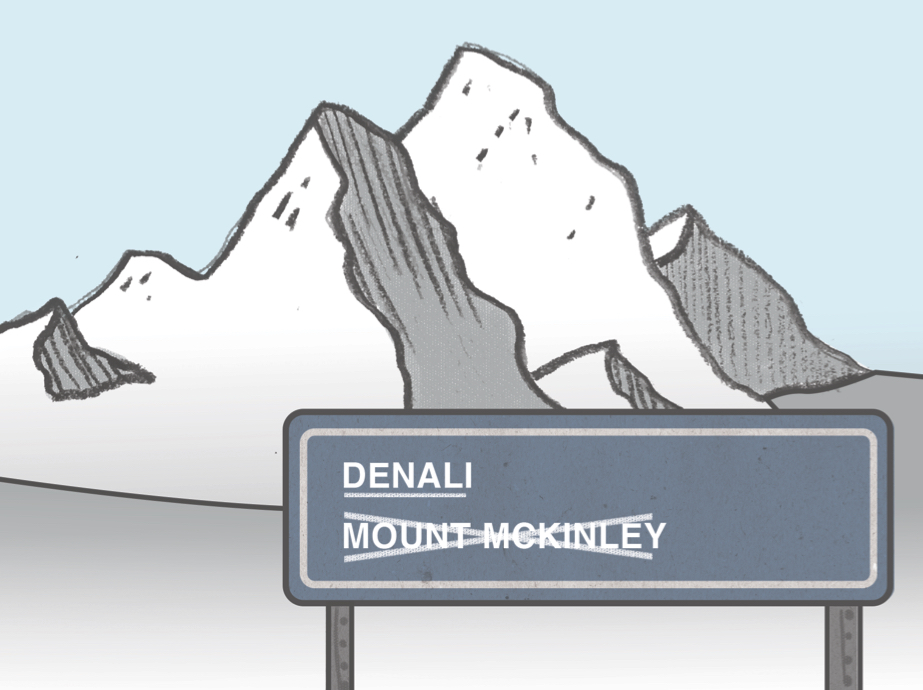

The Obama administration recently ended a decades-long dispute in Alaska by renaming the country’s tallest mountain.

Denali, formerly called Mount McKinley after 25th U.S. president William McKinley, stands as the tallest peak in North America at around 5,900 metres. Denali is the anglicized name for the Alaskan Athabascan word for ‘big mountain,’ a fitting title for an imposing landmark.

Alaskans had been trying to change the name for years, but petty disputes kept the changes from happening. The Alaskan legislature petitioned the U.S. government to restore the mountain’s indigenous name in 1975, but political pressure from an Ohio congressman — who, unsurprisingly, represented the town where McKinley was born — stalled the proposal.

It took another 40 years for an administration to officially change the name. Alaska Governor Bill Walker said, “Place names should reflect and respect the rich cultural history of our state, and officially recognizing the name Denali does just that.”

Geographic formations are often named after prestigious politicians, scientists or other people deemed important enough to justify naming a geographic formation that took tens of millions of years to form after them. It’s a strange concept, but that’s how humans work.

Names are important. They ascribe meaning to the places we visit and the geography that defines our nations. They’re important enough to get right.

Take Canada’s tallest mountain. Mount Logan, in the Yukon territory, is named after Geological Survey of Canada founder Sir William Edmund Logan. By all accounts, he deserves to have a mountain named after him.

But there’s also a colonial aspect to why things are named as they are. Fraser River, the Saint Lawrence River, Mount Robson — all are relics of a colonial era where declarations of conquest were made by rewriting the map.

And make no mistake — our governments are colonial governments enacting and enforcing policy on unjustly-claimed land. Canada is entering an era of truth and reconciliation, and using colonial terminology gives power to a history of violence and cultural genocide.

Restoring aboriginal names isn’t about conceding power — it’s a gesture that lets aboriginal people know that our governments are ready to honour their heritage. It’s about how we remember our history, and what we remember when we look at Canada’s wilderness.

We already have a pretty good track record at utilizing names with First Nations origins.

The name of our country means ‘village’ in an Iroquois dialect spoken in the Saint-Lawrence region. Names of Albertan cities and towns like Okotoks, Ponoka and Medicine Hat — a translation of the Blackfoot word for ‘headdress of a medicine man’ — all have their roots in First Nations languages.

There are plenty more examples of places we know and love with aboriginal — albeit anglicized — names. But we can always do more, and we don’t always get it right the first time.

The location of Nunavut’s capital, Iqaluit, was used by Inuit fishermen for thousands of years because the catch there was so abundant. Iqaluit directly translates to ‘place of many fish.’ But the city shared the name of the bay it was founded on — Frobisher Bay — until 1987. Over 50 per cent of Iqalummiut are Inuit, so naming their city after an English seaman who thought he found a passage to China nestled in a near-Arctic bay is completely senseless.

The Fraser River has multiple names in multiple native dialects. So does the St. Lawrence River. As does every other major river, lake or mountain with a non-indigenous name. We’ll find out in time which colonial names we choose to retain and which we choose to change.

Simply slapping an indigenous name on official documents referring to Canada’s geography won’t make everyone happy. Nor will it change our country’s past. But it’s still a discussion worth having. Acknowledging our shared history needs to happen in the courtroom, the classroom and — not least of all — in how we officially recognize our country’s geography.

Chris Adams, Gauntlet Editorial Board