Think before you tweet after a tragedy

By Melanie Woods, November 19, 2015 —

Like many people, I watched last Friday’s attacks in Paris unfold over social media. For several hours, my phone was constantly buzzing with notifications from the CBC, the New York Times and other news outlets updating me and millions of others on the attacks and their aftermath. Over the course of those hours, the information from news outlets was joined by growing numbers of my friends, family and followers expressing their support for the people of France.

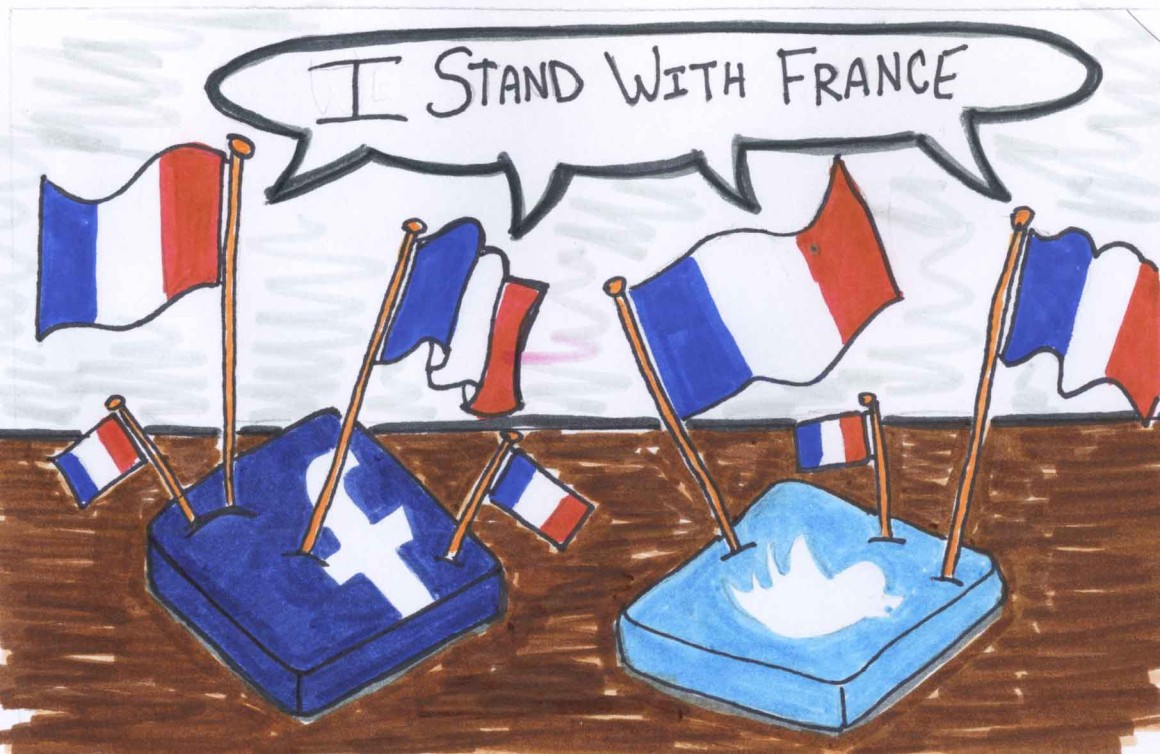

In times of tragedy, our first instinct is to do something. And in the wake of a sudden disaster thousands of kilometres away, all that most people have to offer is words. My Facebook feed was flooded with images of Eiffel Tower peace signs, John Lennon quotes about a world living in peace and red, white and blue profile pictures. It still is.

But these acts of support, while driven from a place of earnest compassion, are also about ourselves.

As much as we care about tragic events when they happen, social media unconsciously pressures individuals to make sure people know that we care and have complex opinions on these events. Faced with a Facebook feed of hued profile pictures, you intrinsically feel the need to do something to show that you care too.

When people changed their profile pictures to rainbows after the marriage equality ruling in America last June, it was to show they are the kind of people who care about marriage equality. When someone posts a quote from a politician, they are telling their friends they wish to publicly associate themselves with that person’s beliefs. Everything we do on social media is an act of self-promotion, whether we consciously intend it or not. And that’s not a bad thing.

It’s not bad to express compassion. Expressions of solidarity do a lot of good in boosting morale and showing people that the world is there for them during a dark time. I’ll admit that I teared up a little looking at images of buildings around the world lit up in the tri-colour on Friday night. But on an individual level, we often rush to make grand online gestures because of the unconscious pressure, not because we’re fully educated.

Before we all make these gestures, we need to do our research. Understand not only what you’re standing with and for, but also what you’re taking a stand against. You don’t need to automatically take to social media and post your opinions and responses to tragic events, especially if you don’t really know what’s going on. You won’t be called out for siding with terrorism if your profile picture isn’t the French flag.

We should stand with France in light of these events, and we’re all free to tell the world how supportive we are. But these gestures of support are just that — gestures. They’re symbols of well-meaning, but we must remember they are performances of “good intentions” rather than actual acts of change.

In situations like this, less is sometimes more. You don’t always have to add your voice to the cacophany of noise on the Internet following events like this, especially when you’re not fully informed. It’s not a contest to see who can be politically correct the fastest. Silence can have power as well.

Few people in France will see your profile picture or read your quoted John Lennon lyrics. More often than not, people will share things for a few days and then return to their regular social media habits. We share and post things to our social media for the benefit of ourselves and the people who follow us. These acts of public solidarity are well-intentioned and heartfelt — but ultimately not much more than that.

Melanie Woods is a third-year English student. She writes a monthly column about modern social justice movements called Social Justice Cleric.