Parks need environmental protection before tourism

By Sean Willett, January 12, 2016 —

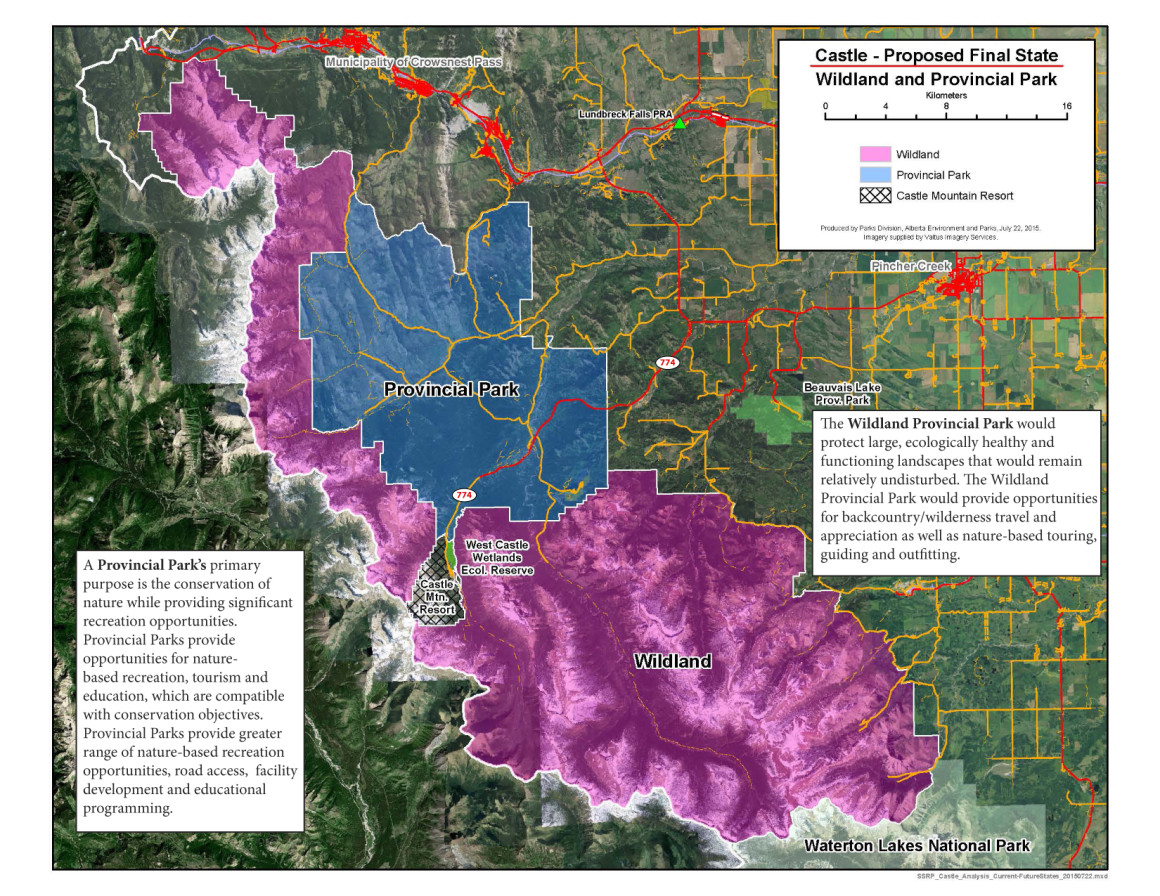

Earlier this year, Alberta’s new NDP government announced that Castle, a large area of land in southwestern Alberta near Pincher Creek, would be protected under Alberta’s parks and wildlands system. Environmentalists were thrilled — Castle is an area activists had been trying to get protected for decades, and it seemed like all that work had finally paid off.

But there was a catch.

When the province released a list of activities that would be allowed in the park, much of the excitement vanished. Alongside typical provincial park fare like hiking and camping, there were a few activities that seemed out of place in a provincial park. Hunting topped this list, as well as the use of snowmobiles and off-highway vehicles (OHVs) on trails and in designated areas.

Strangely, this is a step backwards from the practises of the previous government. Under the Tory administration, there was no hunting in provincial parks and OHVs were banned in all parks except Lakeland, a small area in the eastern part of the province.

But while the NDP’s permissiveness of potentially harmful activities may come as a surprise, the new government’s decision is likely a calculated one. With the Canadian dollar in a free-fall, tourism minister David Eggen said he intends to use this opportunity to promote more tourism into Alberta’s mountain parks.

Opening up these parks to a wider range of recreational activities would encourage even more people to spend time in the Castle during their long weekends — especially since the area is so close to the American border. It’s one thing to draw in the usual hikers and campers, but there’s more money in bringing hunters, snowmobilers and off-roaders along with them.

The problem with this, however, is that these activities can wreak havoc on a natural area. Snowmobiles and OHVs have a tendency to leave designated trails, cutting paths through the forest that allow predators to access areas they normally shouldn’t be able to. And these vehicles can cause immense damage even if they stay on their trails. The Alberta Wildlife Association has found that these trails can divert stream beds and erode large chunks of a forest’s soil over time.

Hunting is a problem for a much more obvious reason. While it can have a minimal impact in designated areas, there is a reason hunting has historically been banned in provincial parks. Killing animals in large numbers upsets ecosystems in drastic ways, a fact that should make the activity naturally incompatible with a protected wilderness area.

Because that’s what provincial parks and wildlands are meant to be — areas where our natural world is protected from the impact of modern society. Tourism is a nice side effect to that, and often does more good for the environment than bad. Money from tourism can be used to bolster an area’s conservation efforts, and the effect of seeing our natural world up close is an invaluable way to teach people to love our planet.

The money that would come from hunters and off-roaders in Castle would be nice, but not if it comes at the expense of the land we are trying to protect. When push comes to shove, conservation needs to be our first priority in our protected wildlands. Otherwise, what’s the point of protecting them at all?

Sean Willett is a third-year natural sciences student. He writes a bimonthly column about environmental issues called Parks and Conservation.