50 years at the U of C from those who know it best

By Fabian Mayer, April 5 2016 —

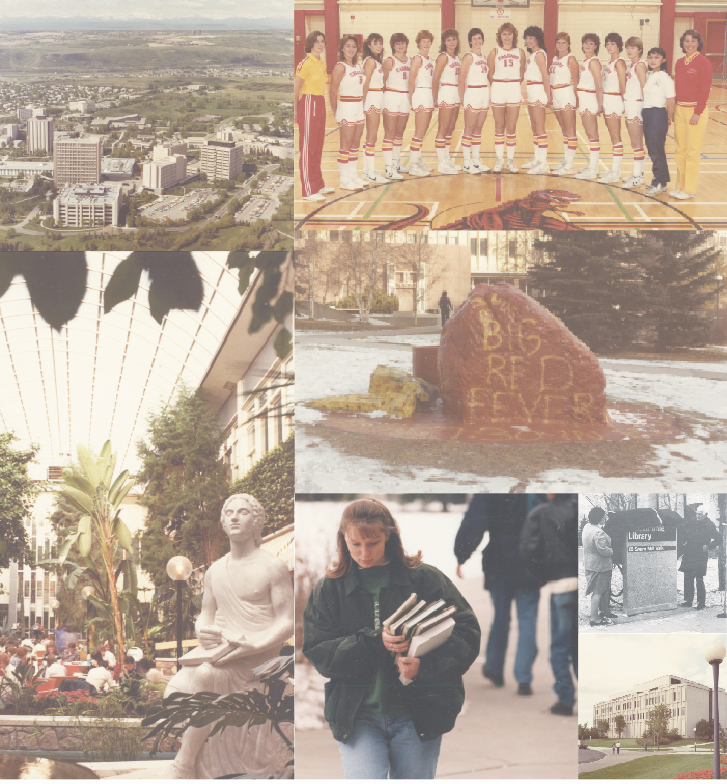

The University of Calgary turns 50 this year. At the time of its founding in 1966, the U of C was a very different place than it is today. There were just a handful of buildings scattered across the treeless, prairie landscape. Campus was on the northwest outskirts of Calgary — whose population numbered about 330,000.

Since then, the U of C has grown enormously. It boasts a prime minister, an astronaut and the creator of Java as alumni. Its dozens of buildings accommodate around 30,000 students. They’ve even planted some trees.

A handful of professors that arrived in the early years of the university remain at the institution. They have witnessed the massive changes in the city and the university over the past five decades. We interviewed some of the U of C’s longest-serving professors to see what they remember about the university’s growth.

Manju Kapoor, Anthony Russell, David Bercuson and Barry Cooper have a combined experience of about 170 years at the U of C. All four had similar experiences joining the university. Biology professors Russell and Kapoor look back fondly on the collegial atmosphere of the science department in the early years, with professors from all departments gathering to eat their lunch in the sole faculty lounge. All recalled the numerous ups and downs of Alberta’s economy over the years.

But the four professors also had many different experiences. Some worried about coming to such a young university, while others were undaunted. A couple planned to leave the U of C as soon as they could, but ended up spending four or five decades here. There’s a good chance a young professor recently hired is thinking the same right now. We look forward to speaking with them in 2066.

[hr gap=”30″]

Manju Kapoor, Biology

1964–present

“I asked them where the university was and they said, ‘this is it.’ I was ready to take a U-turn.”

Manju Kapoor has been at the University of Calgary since its founding. The professor emerita of biology arrived in 1964, back when the institution was still a satellite campus of the University of Alberta.

In fact, Kapoor was hoping to wind up at the U of A. She had applied to their genetics department and appeared to have a job lined up. But after that position fell through, she was offered a job at the Calgary campus.

“I wasn’t sure about the status of the university,” Kapoor said. “I had very little knowledge of the institution.”

Kapoor remembers driving from Winnipeg, where she finished her PhD, to Calgary just a few days before the start of the semester.

“The traffic signs pointed towards the university and then when I got here, there was nothing here. It was all prairie, no trees or anything. Just four buildings.”

Unclear of where she was supposed to go, Kapoor wandered the tiny campus, eventually asking a group of workers for directions.

“I asked them where the university was and they said, ‘this is it.’ I was almost about to take a U-turn and go back to Winnipeg,” Kapoor said.

Two years after Kapoor got lost on campus, the U of C became independent from the U of A.

“That was quite exciting,” Kapoor said. “Just the thought of being at an independent university rather than a second campus of the U of A.”

According to Kapoor, she was one of only about three or four female professors in the faculty of science when she was hired. She doesn’t recall that being an issue.

“In the science department I think it was OK because we weren’t really regarded as females. We were scientists. Interactions with colleagues were really not gender based.”

Kapoor said her research and teaching has kept her at the U of C all these years. After over five decades here, she’s glad she decided against taking that U-turn.

“I had good innings here. I’m happy with my decision.”

[hr gap=”30″]

David Bercuson, History

1970–present

“I had a lot of senior professors phone me up giving me hell for raising this issue in the first place.”

David Bercuson was finishing his PhD at the University of Toronto when the U of C became autonomous from the U of A. But he didn’t know much about that at the time.

“I didn’t even realize that it was the U of C,” Bercuson said. “When I first started corresponding I was sending my letters to the University of Alberta at Calgary — then I saw the letterhead.”

Despite botching the name, Bercuson was offered a job at the U of C in 1970. The young academic didn’t think he would stay for long.

“To be frank, everybody thought this is a good ‘single A’ team to go out and start your career with. When you get better, we expect you’ll settle in Toronto or whatever with all the big leaguers,” Bercuson said.

But something convinced him to stay. The 26-year-old became seriously ill, and needed back surgery that put him out of commission for over a month. Since he had only been in his job for a few months, he wasn’t eligible for disability insurance.

“The department head at the time I don’t even think ever reported that I was absent because of my illness,” Bercuson said.

Other faculty members filled in for him while he was gone.

“They all thought, ‘well we’re all going to pull together and cover for Bercuson so he doesn’t lose his salary,’” Bercuson said. “That started me thinking, this is a pretty good place.”

Bercuson was involved in the push for collective bargaining for faculty a few years later. According to Bercuson, the faculty association could present their case to the Board of Governors, but didn’t have much real power.

“The cynical among us called it collective begging,” he said.

Bercuson and a few colleagues held an unofficial referendum among the university’s various faculties to see where faculty stood on the issue.

“I didn’t realize that without tenure, one wasn’t supposed to make waves,” Bercuson said. “I had a lot of senior professors phone me up giving me hell for raising this issue in the first place.”

But Bercuson says he wasn’t worried about losing his job as a result of the rabble-rousing.

“I think I was too dumb to worry about it. Too driven by my own sense of righteousness.”

Eventually, the board bowed to the pressure. And now, 46 years after he arrived, Bercuson is still a professor in the history department. He’s also the director of the Centre for Military, Security and Strategic Studies.

He’s kept an unofficial count of the downturns the province has experienced over the decades. Bercuson’s tally sits at seven, and he remembers one such downturn soon after coming to Calgary

“That worry comes back and every time it happens I say to myself, ‘why didn’t we learn from the last time.’”

Bercuson laments the rise of the U of C’s bureaucracy, among other things.

“I honestly think I’m getting as much spam from inside the university as I’m getting from outside the university,” Bercuson said. “A lot of it I think is just silly. Like why are you bothering me with this. I hit the delete button.”

In the end Bercuson says his love of teaching is what’s kept him here.

[hr gap=”30″]

Anthony Russell, Biology

1973–present

“By the time we decided we like it here, it was too late to bring the stuff over. We had crap anyways.”

Professor emeritus in biology Anthony Russell remembers the first day he set foot on the University of Calgary campus on Aug. 20, 1973.

Professor emeritus in biology Anthony Russell remembers the first day he set foot on the University of Calgary campus on Aug. 20, 1973.

Russell, a native of England, was offered a post-doctoral fellowship at the City University of New York, but decided to come to the seven-year-old university in Calgary instead.

“I think living in a country where guns are not freely available gives you a mindset to make you wary of going somewhere where they are,” Russell said. “It was a sort of naïve assumption that it was more dangerous.”

Russell didn’t know what to expect when he arrived. The university offered to pay to transport his family’s things to Calgary under the condition that, if he left within three years, he would have to pay the money back. Russell wasn’t sure how long he would stick around, so he declined the offer.

But he decided to stay. And despite being in Calgary for over three decades, Russell never had many of his items shipped over.

“We came with what we could carry in our hand baggage and some kitchen knives and pots and pans. By the time we decided we liked it here, it was too late to bring the stuff over,” Russell said. “We had crap anyways.”

Russell said one of the biggest changes to campus came when Calgary hosted the 1988 Winter Olympics. Prior to that year, he says there was only one place to get food in MacHall, and it was only open from 8:00 a.m.–4:00 p.m. According to him, the Olympics made campus much more vibrant.

“It opened up MacEwan Student Centre and it made it a very different place to be after the formal sort of business day.”

Russell said attitudes on campus changed alongside its physical form. He remembers the West Campus lands being treasured as some of the last short grass prairie area in the vicinity.

“Many years ago they wanted to put one field hockey field on West Campus and there was absolute outrage on campus that that was going to be done because it was spoiling West Campus. Then the whole thing gets bulldozed and nobody says a word.”

[hr gap=”30″]

Barry Cooper, Political Science, 1981–present

“The attitude then was ‘of course we’re in the business of offending people.’”

Barry Cooper is a relative newcomer to the University of Calgary. The political science professor arrived at the university in 1981, 15 years after the U of C’s independence. Cooper has been in Calgary ever since, giving him 35 years of teaching and research experience.

He recalls the university having a brasher attitude in his early years at the institution.

“The attitude then was ‘of course we’re in the business of offending people,’ because most parts of our society have these unquestioned assumptions about what is the right way of looking at things,” Cooper said.

That adversarial attitude helped establish the U of C’s broader political identity, which Cooper was an integral part in defining. The Calgary School — a branch of conservative political thought — developed almost by accident on hunting and fishing trips with colleagues in the department.

“We would talk about our research and it turned out that we had overlapping interests,” Cooper said. “All of us had fairly profound misgivings about the kind of lefty-liberal view of most academics. I mean we just disagreed with it. And that was kind of unusual because it was spontaneous and was peculiar to this university.”

This attitude helped Cooper make national headlines in 1987 when he and graduate student Lydia Miljan conducted a content analysis of CBC’s Alberta coverage. The resulting paper alleged “a persistent left-wing bias and a kind of enduring animus against western parts of the country.”

“We wrote this paper and presented it at the political science meetings. There was pressroom and I went there and left three or four [copies] and it turned up on the front page of the Globe and Mail. It got the CBC in a real snit,” Cooper said.

Cooper said former CBC president Pierre Juneau sent a letter to former U of C president Norman Wagner urging him to fire Cooper. He noted Wagner’s sense of humour before describing what happened next.

“Norm made a photocopy of it and said ‘would you like to draft a reply for me?’ And I said I’d be delighted to.”