Haviah Mighty talks the Polaris Prize, race and hip-hop

By Troy Hasselman, October 24 2019 —

Fresh on the heels of winning the Polaris Music Prize on Sept. 16, an annual award given to the best Canadian album based on artistic merit alone, which includes $60,000 worth of prize money, Haviah Mighty’s career has scaled new heights. The Brampton MC’s album 13th Floor looks at themes of racism and discrimination through the lens of the number 13, relating it to the 13th Amendment, the unluckiness of the number 13 and the practice of buildings not designating the 13th floor during construction. The album speaks for Haviah Mighty as an overlooked person — overlooked as a black woman in Canada and as a woman in a male-dominated hip-hop field.

Mighty is also a member of the all-female hip-hop group The Sorority, which was formed between herself and three other MCs after a group cypher between the four on International Womens’ Day in 2016. Mighty will be playing at Calgary’s #1 Legion on Nov. 8 as part of the Femme Wave Festival. The Gauntlet caught up with Mighty to speak about the Polaris, hip-hop, racism and spaces for women in music.

The Gauntlet: What’s the last month of your life been like?

Haviah Mighty: Pretty insane. Definitely getting used to the fact that there have been a lot of changes. I’m still processing the fact that these changes are happening and trying to understand what they look like. I’ve been doing a lot of shows. Obviously, the Polaris happened. I look at it as another show, but also an award experience — a winning award experience, luckily. I’m processing all of that stuff. There’s a lot of preparatory talks of what’s to come next, tour talks for 2020. Discussing what we want to do with the financial winnings from Polaris, what new assets we want to create from the album. Just figuring all of that stuff and balancing it out. It’s an amazing feeling, because it feels like more security for this career and more options and opportunity to continue to do what I’ve been doing.

G: Before you were rapping, you were singing. Do you remember a moment where you fell in love with hip-hop?

HM: Kind of an era I fell in love with hip-hop — the early 2000s era. The 50 Cent era with G-Unit, Ludacris, Dipset with Cam’ron and Juelz Santana. There was this era of being in a rap crew and also being a solo artist and I fell into hip-hop in that era. That was in grade four, five or six for me, so I’m using the computer on my own and my parents are giving that little extra bit of trust. You’re finding a little bit of individuality now, you can stay after school for a little bit and talk to your friends and start to formulate opinions on things that you do and don’t like.

G: You’re the first hip-hop artist to win the Polaris Prize. How do you feel about the recognition that Canadian hip-hop is getting and the current state of Canadian hip-hop?

HM: I think there’s been a big void in recognition that Canadian hip-hop has been getting. There’s been a lot of great records that have come out of Canada. I definitely don’t think of Canada as a hub where hip-hop is a great place to shine with a lot of notoriety. I think a lot of the topics on the album speak to that, maybe not specific to hip-hop but more specific to culture. Something like the Polaris exists and it’s focused on artistic merit alone, I also think the most hip-hop albums ever were considered this year as well. There were a few hip-hop records considered for the short list, at least three, and I don’t think they’ve ever had that before, so that shows a good shift in a positive direction. It’s a large platform and wide format in front of the whole Canadian music industry, with so many people in that room who have the possibility of opening doors. They are tastemakers for so many different things. I think it’s great that more hip-hop is being recognized, it means that more stories can be told and more narratives can be shared and more opportunities can go to people that don’t normally receive them.

G: There’s this global perception of Canada as this utopia without racism or misogyny — of course this isn’t true. Could you talk about the gap between what people think of Canada and what Canada actually is?

HM: I’ve been told so many times “Well you live in Canada, so it can’t be that, you don’t really experience racism because you’re Canadian.” In order to process that thought, I’d have to dismiss my own narratives and determine the things I’ve felt were inaccurate, because I’ve felt certain things and it sure felt like racism to me. I felt it here in Canada. Canada was built on the backs of racism, just like America was, and I can understand that it’s not felt the same by everybody, but I think in Canada racism just looks different than in the States. It’s a lot more discrete. Just because you can’t see it doesn’t mean it’s not happening. The fact that it can’t be seen sometimes makes it more dangerous because of the way you have to navigate it. I’ve navigated racism my entire life. I feel the reason why I’m as adaptable as I am is that I feel that I have to be, as a survival mechanism. Being able to navigate different realms with people that don’t look or talk like me makes me more powerful, because the opportunity to refuse me is forefront as a dark skin black female. Where you have hardships is applying for a job, and sitting with a manager across the table who doesn’t necessarily think they have a racist bone in their body, but they hire what’s familiar to them. When they don’t understand you and you’re unfamiliar to them you just don’t become under consideration. You have to know what they’re willing to hear from you. At times that means silencing who you are as a person in order to cater to a manager. Working in certain industries for some people can’t be done, having dreads. Working as a bartender or server or host at certain restaurants, they’re never going to hire a girl who doesn’t have straightened hair. It doesn’t matter about the race — black, white, it’s going to be a girl with long, straight hair that hangs down. The beauty standard for certain restaurants is European, and I’m not European. I know so many black women who, in order for them to fit in industries they have to wear their hair a certain way, or put on weaves to hide their natural hair. Maybe they don’t want to dye their own natural hair, so you have to put unnatural hair into your real hair and damage it because you can’t wear your own hair in the way that you would be expected to in order to work in those service industries.

It’s all of those different things that different types of people have to do in order to adapt into a society that has covert racism like Canada does. People are more willing to talk about racism that’s obvious and not as willing to talk about racism that isn’t as in your face. I try to speak on some of those themes on the album and the way that it affects people. I think some people don’t think about how not simply being looked at can affect you and being asked why you are somewhere when you have the right to be there can affect you. It doesn’t look big and they aren’t necessarily being asked those questions. I think if we were to look into the history of Canada we’d realize how much it bids on slavery and how intrinsic slavery is to the development of Canada. Because those narratives are silent and the racism looks quiet, we pretend that it’s not there when it very much is.

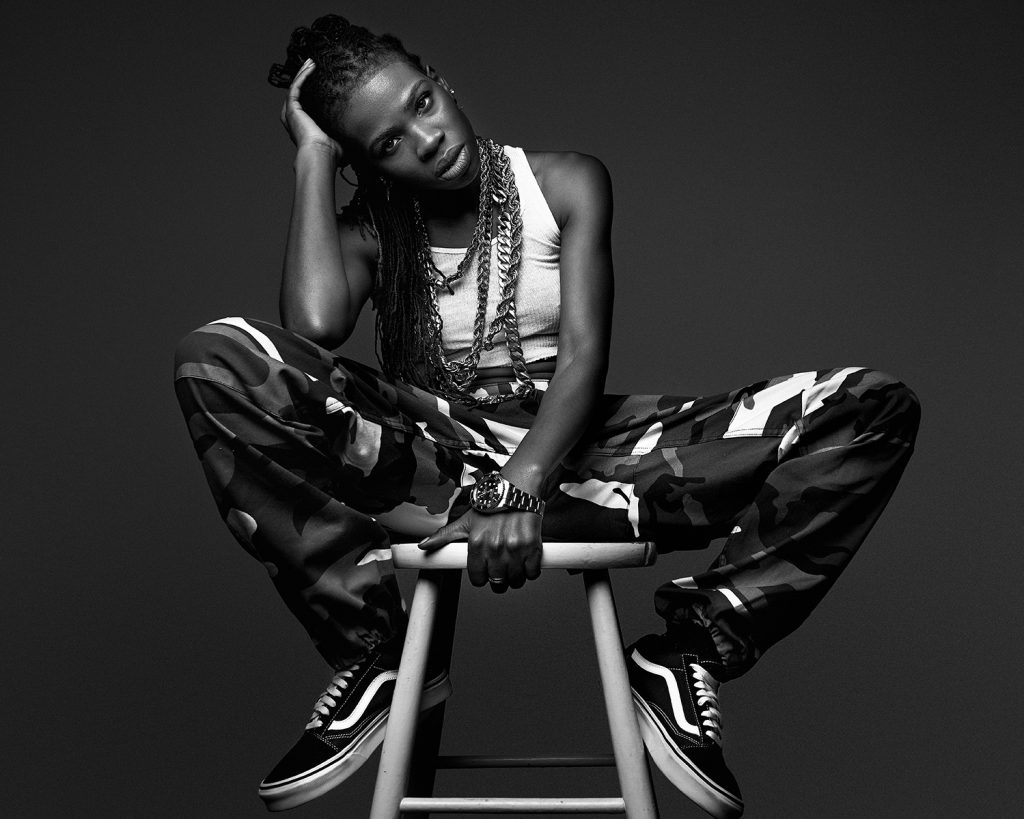

Photo of Haviah Mighty. // Photo courtesy of Matt Barnes.

G: Your music has a lot of diverse instrumentation with influences from all over the world. You were raised in Brampton which is a very diverse city. Has growing up in Brampton had an influence on your music?

HM: I think so, yeah. I experienced more racism in Toronto in my early years than I realized I was facing in Brampton. I’m sure I did, but in Toronto it was much more blatant. Maybe because I was younger, maybe because of the area. Brampton for me was true multiculturalism, where I grew up in Toronto it wasn’t very multicultural. It was very white, and on top of that we didn’t have a lot of money so it was very poor. I didn’t have a lot of experience being outside of my house because there was this understanding that after school you come home and you don’t play outside of the house even though there’s a park right there because we don’t know the people here, and they make comments and throw bricks at the house and could harm you. When we came to Brampton, we moved to a neighborhood where there were Portugese kids, black kids and Indian kids and they all went to the park together. Were there still racist moments? Absolutely. Maybe black kids got into a fight with the white kids and there would be comments and it would be somewhat specific to race, but the ability to get out of my home and see other black people and other races and talk to them and enjoy myself as a young person, I wasn’t able to do that in Toronto. I was very grateful for Brampton and the changes it showed me because I was able to talk to people, and determine how I felt outside the walls that were my home without my Mom and Dad breathing down my back. I was able to build my own personality a little bit.

G: You’ll be playing in Calgary as part of the Femme Wave music and arts festival. As a woman in a male-dominated hip-hop field, could you talk about spaces for women in music?

HM: I think it’s really important for there to be spaces for women in music. These spaces are important to all marginalized groups in whatever facets they exist in. Women are definitely a marginalized group when it comes to musicality at all, in the ways we get to express it and the opportunities we have to express it. I also think it’s important to create inclusive environments for both men and women. I do think it’s important to have events for women and just for women, because there’s so many events that even though they don’t say “Just For Men,” only men will be considered. But I also think it’s important for women to be a part of events that men are a part of and have them be a part of regular events. I think it’s also important to have women-specific events, I think as long as that’s not the only way that an entity is including women, it’s progressive for sure.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity