Film Review: The Zone of Interest

By Jyotirmoy Gupta, March 14 2024—

Some critics have called Jonathan Glazer’s new film the most violent of the year. I went into the theatre expecting a very different film from what I saw. The film deals with the subject of the Holocaust but from the Nazi point of view. And no, it is not asking us to empathize with the Nazis, but rather it attacks our potential for apathy. It is a film that asks for the viewer’s attention and self-introspection to put forward its point.

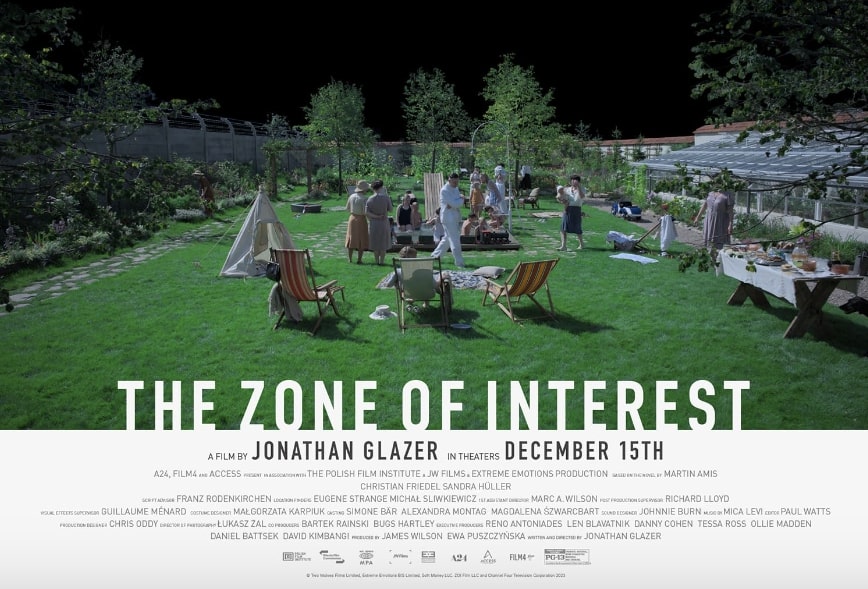

The film starts with two minutes of black screen and background noise. The start sets the tone for the rest of the film. It tells the viewer that to see the film, you have to hear it first. We are introduced to the film’s main characters, Rudolf Hoss and his wife, Hedwig, and their children picnicking near the river. The film first establishes an air of normalcy around the family and their lives. But slowly, as more is revealed about their lives through daily conversations, we realize that Rudolf Hoss is the chief commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp and he lives this idyllic lifestyle just next to the camp.

The film’s violence doesn’t lie in the act of killing but in the absolute ignorance of it. There is a scene in the film where Hedwig is coddling her newborn child and relishing the beauty of the dahlias growing in the garden while you hear the screams of people being gassed in the background. Once you realize what the background noise is, it never leaves you. It keeps getting louder and louder with every scene in your head, and you question how Hedwig can not hear it. Hedwig’s obsession with her house and the garden is the driving force of the film. She is deaf and blind to the atrocities around her, for her Auschwitz is a dream home, a perfect place to raise her family.

Philosopher Hannah Arendt in her book Eichmann in Jerusalem coined the famous phrase “the banality of evil”. The book explains in detail how many Nazis thought that they were not committing any crime but rather just carrying out their duties. The Zone of Interest is the cinematic exploration of that philosophy. A visual and aural tension is created by showing the Hoss family as a normal family, completely oblivious to the atrocities in which they are complicit.

The film did not create a big box office buzz like Oppenheimer or Barbie, but it is truly an achievement in cinema, a film that will be talked about for years to come. Filmmaker Stephen Spielberg called it the best film dealing with the subject of the Holocaust after his magnum opus Schlinder’s List. Director Jonathan Glazer pushed his creative limits, by setting up ten hidden cameras and 60 microphones in the house and then walking out of set. The actors were given instructions about the scene, and then the director and his team would observe footage from the basement as if reviewing security footage from different angles. The film uses no artificial lighting and was filmed on location just metres away from the real camp. That is why the film feels so realistic as if we are in the house with the family.

Because of its abstract and unusual nature, production houses were very skeptical of funding the film, and it took Glazer ten years to complete it. But as you watch the film, you understand the decisions made by the director and the hard work that went into it. The use of infrared footage in the film has to be one of the most meaningful and kitsch-free uses of the technique in recent film history. Although it will surely get snubbed at the Oscars, this film should be praised for pushing the boundaries of cinema. To limit the film’s audience by calling it artsy is an injustice to its potential.

Without revealing much about the end, it is important to say that this film is as much about the present as it is about the past. In this world of social media, where we constantly see and read stories about war atrocities, we forget the banality of scrolling. As we live our everyday lives, somewhere everything that defines humanity is falling apart. This film doesn’t seek to give visual pleasure; rather it is a wake-up call for introspection.