A Search for modern love: Celine Song and The Materialists

By Salam Jesudamilola David, September 22 2025—

Light Spoiler Warning

Weeks after exiting the theatre, I thought I had finally managed to leave The Materialists behind.

It was no easy task. Those shots of soft hues lighting the night, our protagonists set against one another — across a dinner table, on an empty street, slipping through gridlock, monologuing sometimes for minutes on end. Even then, you sense leaving the table incomplete, unheard.

All of this lingered, and left me with emotions that felt impossible to reconcile, to impress any meaning on.

Then I came across a clip of film director, Celine Song, defending her movie. Pushing back against an interviewer describing the film as “broke boy propaganda,” she spoke with much spirit and not a little dismay.

Song turned what was clearly meant to be algorithm-friendly TikTok bait into an two-minute-long rebuttal.

Her response was brilliant, and as stern as the subject matter required. With it, she laid out the heart of her most recent work, this desire to protect what little we can from the grasp of commercialism. To treat love as love, and people as people — to be judged by their virtue, and not immediate value.

Unfortunately, as concise and cutting as it was, Song’s retort describes the theme of a movie that could have been, which frustrates faithful viewers. The Materialists we got meanders, is unbalanced and leaves its audience with more questions about modern love than it answers.

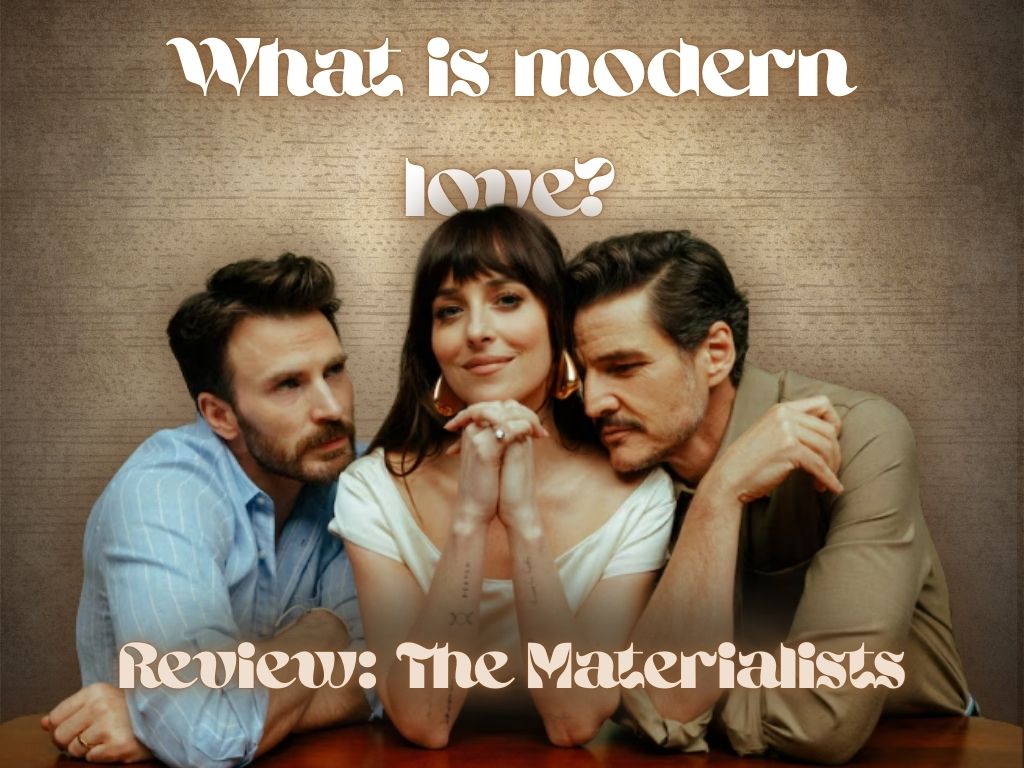

The plot follows Lucy Mason (Dakota Johnson), an employee at a matchmaking agency who is caught in a love triangle between a seemingly beyond perfect match in millionaire Harry Castillo (Pedro Pascal) and down on his luck ex John P (Chris Evans).

Lucy is ruthlessly analytic.

The movie establishes this early on as she sits high on a windowsill and considers the potential effects of a gruesome limb-lengthening surgery on a man’s dating prospects. She tells a would-be runaway bride to dwell on the jealousy her groom evokes in her sister. She markets her agency to suitors and strangers alike, Lucy Mason is the materialist.

But of course, this is not all to her.

There is a softer side to Lucy. Glimpsed in her doggedness to find a match for a seemingly hopeless client in Sophie, and in the soft way her eyes light up when she reunites with John.

The movie’s conflict rests on this contrast. Which side of Lucy will prevail, Harry or John, the Materialist or the Lover?

It seems a simple task, establish the choices offered to our protagonist, making her eventual decision thematically relevant. If done effectively, Lucy’s story should read as a triumph of romantic love over vanity.

The result is sadly lopsided.

Scenes between Harry Castillo and Lucy crackle. Their conversations brim with morbid wit. Over dinner, each dissects the other, ranking and re-ranking themselves in the great dating food chain.

Everything is an integer for them: height, age, weight, wealth.

They size each other up, speaking in parlance that would be more recognizable at a car dealership than over a candlelit meal. But it still feels right seeing them together. Speaking, one to another, as equals. Who better to forgo love for ease, you ask yourself, than two people who never much believed in it anyway?

In contrast, John and Lucy fall flat.

Johnson’s trademark coolness meshes poorly with Chris Evans’ eager portrayal of his character. Is this love? I wondered to myself as over and over again he pined, and she recoiled.

The problem with their relationship is the problem with The Materialists — it never feels like Lucy is really in love with John. There’s a sense of fondness, but the movie never suggests there is something she isn’t letting herself feel.

What we get instead is frustration right up until the closing minutes of the third act — frustration with John for not accepting their limits.

There’s a lot to say about the poor state of modern dating, and this movie does so brilliantly, but it offers no real alternative. The warmth we are supposed to be drawn to rings hollow. It leaves us wondering what romantic fulfillment should even look like. The Materialists starts off with a similar question; it takes us back to the first marriage and bids us wonder what it was that drew those two together, outside of status, wealth and “compatibility” calculators. At the end of it all, we are left wondering still.