Review: UCalgary SCPA’s Women of the Fur Trade

By Edie Stowell, December 20 2025—

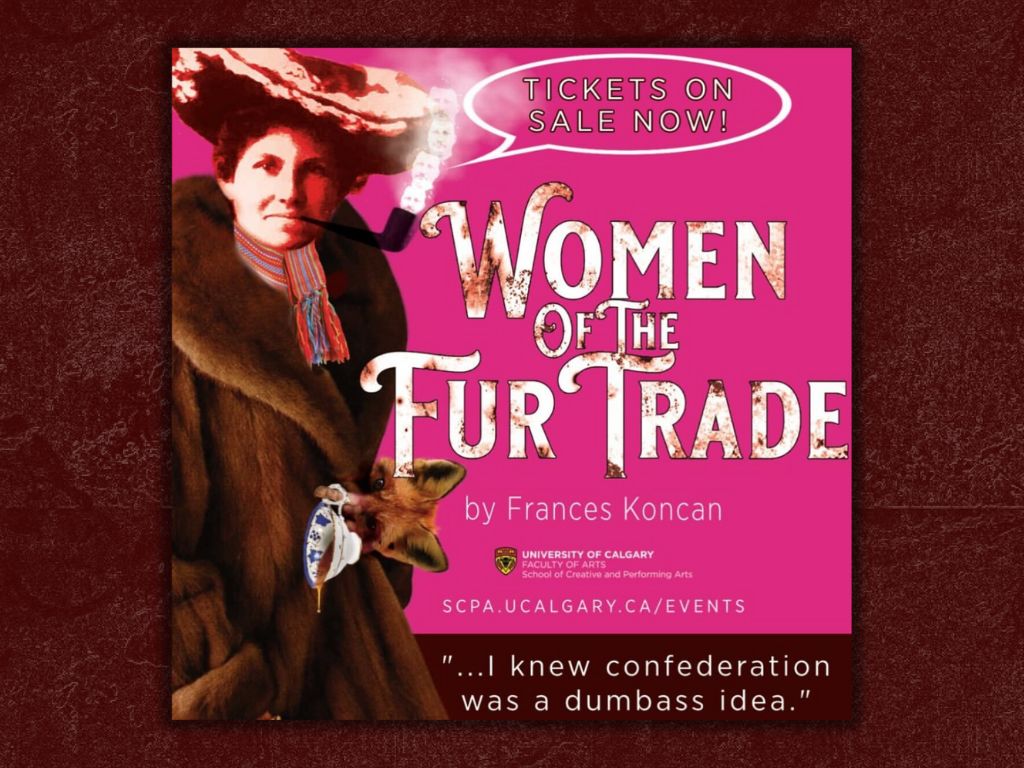

University of Calgary’s School of Creative and Performing Arts ran their production of Women of the Fur Trade on Nov. 1 to 8. Written by Frances Končan, Women of the Fur Trade takes place in the time of the Red River Rebellion. The script captures this period in a balance between realistic and fantastical, comedic and reflective, leaving no question as to why performances have sold out around Canada before reaching the Reeves Theatre. Director Geordie Cowan currently studies Metis identity in Canadian theatre in his MFA at Ucalgary. This performance is part of reclaiming that identity and history, showing how oppression leaves its imprint in the telling of history and present day.

This play takes place in the mid 1800s in the Red River Colony, located in present-day Winnipeg, Manitoba. This place was a major site for the fur trade, and was inhabited by Metis, Cree and Ojibwe people; and later on an influx of European settlers. In 1836 The Hudson’s Bay Company claimed ownership to the colony, until the 1860s when the company was sold to the Canadian government. As threats of expansions and land surveyors loomed on the unconsidered inhabitants, a rebellion formed, lead by Meti Louis Riel.

Here we meet the three women of the fur trade, trapped in a fort and sharing their thoughts on the rebellion. Marie-Angelique, played by UCalgary Drama student Laura Astiz Andrade, is a young Metis woman who throughout the narrative becomes increasingly eager to join the rebellion as Louis Riel’s “number one fan.” Andrade plays Marie with vibrant enthusiasm bordering on naivety, with wonderfully animated body language. Nakota Starr Tobias plays Eugenia, an Ojibwe fur trader, lending a dry humour delivery that suits the character’s realistic outlook on events. Throughout the show Tobias’s facial expressions provide gratifying reactions to the other characters. The third woman, Cecilia played by Sophia Garcia, is an English settler waiting for the return of her husband. Garcia presents Cecilia through a cheery accent and hilarious facial expressions, satirically optimistic and ignorant about the settlers position in the colony and Canada. Cecilia conforms to her role as an obedient wife in the patriarchy to the point of delusion. She is a fan of Thomas Scott, a Scottish Protestant and member of the Canadian Party. As the characters talk, Marie and Cecilia argue over their conflicting crushes and societal positions, raising the question as to how far their friendships can go. Marie ties up the act by asking Cecilia if she really believes in the expansionists slogan “manifest destiny.”

On the other side of the stage enters Louis Riel, played by UCalgary alumni Benjamin Beston-Will, and Thomas Scott played by drama student Stephen Brooks. Beston-Will entered the stage with a loud, confident voice, contrasted by Brooks’ temporary timidness. Drama proceeds when Riel gets a letter from Marie, and Scott writes back instead. Louis Riel becomes motivated to return to Red River once he hears Eugenia is with Marie.

I am not an expert on Metis history, but while watching I questioned why the narrative portrayed Riel as driven to the rebellion because of a romantic fling, and gets increasingly mentally unstable. This was a time when Metis oppression was increasing, and their agency was being threatened along with all Indigenous people, and I would think Riel had deeper main motivations. In other interviews Končan emphasizes that this play is not to be taken as a history lesson.

The next scene made great use of lighting work combined and soundtrack, operated by Nico Charette (lighting) and Juno Fairweather (music). A fantastical scene occurred as Cecilia read the letter sent to Marie. Cecilia’s voice morphs into the exaggerated voice of Louis Riel’s as he walks through the fog machine’s purple cloud, then into Thomas Scott as he writes the letters. Marie’s fan girl reactions were the cherry on top, making the whole audience laugh.

Letters are also used as storytelling when Eugenia portrays her anger towards the Canadian government in a letter to the prime minister, and Marie showcases her complex relationship in a letter to her mother.

Scott and Riel’s dialogue and dynamic was both funny and explored their different views on the Red River and land rights. Their tumultuous dynamic ends in an argument, leading to Thomas writing a letter to John A MacDonald, exposing Louis Riel’s plan of rebellion. Despite this betrayal being inevitable from the beginning, it caused audible gasps.

When she returns to the fort, two years have passed. In that time the Red River Settlement became a provisional government led by Louis Riel, and the Manitoba Act passed, creating the province. Cecilia’s husband and Thomas Scott were executed on account of treason, and Louis Riel fled to the US.

Even though this was a small cast of five, the setting was a character in its own right. The stage was split into tree trunks of a forest that transitioned into the walls of the log fort, covered by framed portraits of men. From the real Thomas Scott and Louis Riel, to John A MacDonald, to Keanu Reeves, to Pedro Pascal, to “Mathew the Incompetent Blacksmith.” The setting also reflected the women’s position in society. In the beginning Cecilia and Marie are unable to leave, while Eugenia can come and go, or walk through doors and Marie fantasizes about one day finding and walking through the door herself. Near the end of the show, as the political events constrict around the women, Marie can no longer find the window she once left from, and Eugenia can no longer find her door.

In the last act the threat of the Wolsey Expedition looms, when troops from Ottawa were sent to Manitoba, and Louis Riel is being condemned for murder in Regina. The scene of Riel’s hanging again makes use of creative lighting. The stage is dark, other than a white spotlight on Louis Riel, which turns a dark red at his death, shadowing his eyes when he looks up to deliver his final words. Beston-Will does a haunting job during this scene, swaying side to side then stilling as he speaks his lines, “My people will sleep for one hundred years, but when they awake, it will be the artists who give them their spirit back.”

The women, in painful realism, have no choice but to bear the news and circumstances. They come back together in their friendship andreflect on the rebellion and their loss. They then call back to the beginning of the play, with the same string music soundtrack, making tea and playing a game. This time they dawn big fur coats, preserving their relationships and love for each other, while being ultimately changed.

Costumes were well done, they fit together and seemed cohesive with the time period. My favourite costumes were Marie-Angelique’s dress, with a red Meti sash and a ribbon skirt with many layers that complimented Andrade’s big, emotion filled movements across the stage. I also enjoyed the detail in her and Eugenia’s accessories and hair. In the end scene the grand fur coats tie the women, the themes and the history of the Red River colony together.

I enjoyed this performance and laughed out loud with everyone seated around me. I admired the technical production that brought the stage to life and was drawn to both characters and their relationships. The actors did justice to each witty and humorously shocking line, they also did a great job at portraying their conflicts with the outside world and the subtle tension building between their different positions in society. They raised questions that are still prevalent in the present day, including who tells history? How are friendships affected by culture, class and political position? And, who has a right to a home in a particular land?