Trigger warnings protect vulnerable students

By Kate Jacobson, April 2 2015 —

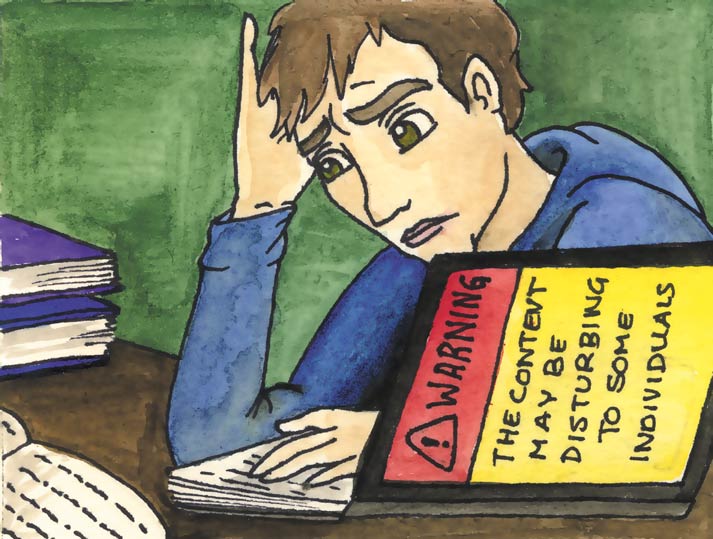

Universities should use trigger warnings so students have the necessary information to make choices about their own mental health.

Trigger warnings are short sentences included before discussing a distressing topic, like “trigger warning: graphic depictions of sexual assault.”

Critics of trigger warnings claim they infringe on free speech and stifle debate. This isn’t true. There is a difference between not discussing a difficult topic and warning students what that topic is.

Professors will continue to discuss upsetting topics like rape and genocide. But there’s no harm in letting students know when something distressing will be discussed in class.

Trigger warnings aren’t an invention of liberal academia. Movies have warnings for scenes of sexual assault. There are restrictions on television advertisements. Cigarette packages warn you of the health risks of smoking.

Trigger warnings don’t stifle speech. They’re a simple and helpful courtesy.

University is about being confronted with ideas, even ones we don’t like. But there’s a difference between dealing with subject matter that may be uncomfortable and forcing students to encounter traumatic material on a whim.

It’s a common misconception that being triggered means feeling upset, sad or angry when confronted with a topic. When someone is triggered, they’re experiencing a psychological response as a result of surviving trauma or experiencing sustained and systematic abuse.

Most of us feel uncomfortable when confronted with topics like rape. Trigger warnings are not for us. They’re for the student who was sexually assaulted as a child, and who doesn’t want to relive one of their worst memories in the fourth row of a lecture theatre.

University students are adults. We can make decisions about our own mental health. This includes deciding what potentially triggering material we want to view.

When used appropriately, trigger warnings won’t censor professors, even those who take pride in being controversial. These content warnings don’t stop professors from being able to say what they want.

But they do mitigate the potential harm caused when students come into contact with material that would cause them psychological distress.

If an instructor is planning to discuss sexual assault, a quick email to students 48 hours before the lecture would work. Students could contact the professor and request accommodation if we felt the subject would be triggering.

But it’s impossible to make responsible decisions about mental health if we don’t have access to the necessary information.

Trigger warnings aren’t about babying or coddling students. They’re about respecting students enough to give us information on the classes we’re taking so we can make informed and responsible decisions about our own mental health.