No one left to corrupt: The influence of business on American politics

By Christian Lowry, December 4 2020—

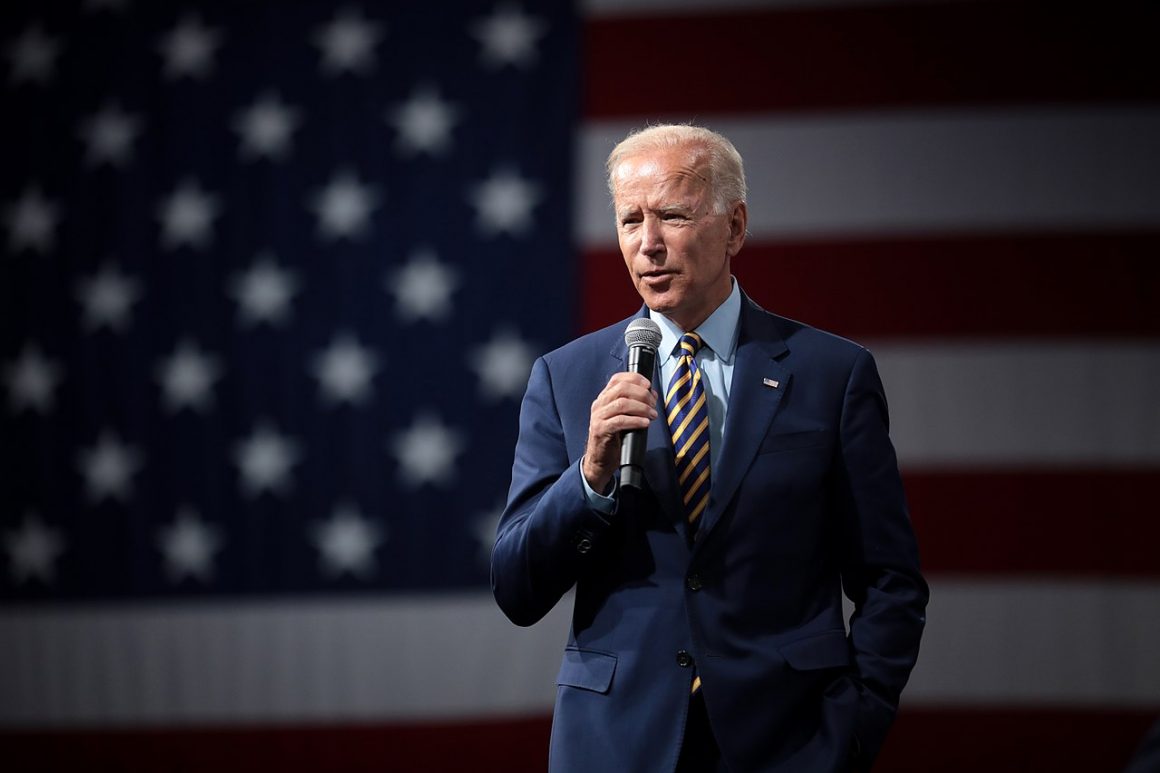

Even though Joe Biden has beaten Donald Trump in the United States presidential election, it is doubtful that many of the nation’s most pressing problems will be addressed.

Public trust in the United States government is at a remarkable low. According to the Pew Research Center, which conducts annual polls of public confidence in government, the proportion of Americans who trust the federal government “to do what is right” fell from 77 per cent in 1964 to 17 per cent in 2019. This decline has continued under both Republican and Democratic administrations. Essentially, there is an increasingly widespread perception that the United States government is no longer working in the public interest. A similar poll conducted last year found that 51 per cent of respondents viewed the gap between rich and poor as a “very big problem.” 52 per cent of respondents thought the same about “the way the political system operates”, as did 53 per cent about “the role of lobbyists and special interest groups in Washington.” Lastly, 67 per cent viewed “ethics in government” as a major problem.

To say that “our” elected representatives are being corrupted by private interests presumes that representative government was always meant to serve the people’s will, and is a generally clean and fair system with some notable anomalies. I believe the converse to be true — the American political system is generally riddled with flaws, with occasional outliers. Although some noble personalities selflessly defend the interests of their constituents, they are the exception, not the rule. The American political system was not designed to serve the common person. It was designed to protect the accumulation of private property and social privilege.

This may seem like a radical position, but it was one shared by the individuals known today as the “Founding Fathers,” who feared that it would be realized by the wider population. James Madison, the fourth President of the United States and the writer of the Virginia Plan (the prototype for the U.S. Constitution) argued during the Constitutional Convention of 1787 that “if elections were open to all classes of people, the property of landed proprietors would be insecure,” and that the purpose of government was “to protect the minority of the opulent against the majority.”

Alexander Hamilton, another Convention delegate and later the first Secretary of the Treasury under George Washington, agreed, saying, “All communities divide themselves into the few and the many. The first are the rich and well-born, the other the mass of the people…Give therefore to the first class a distinct, permanent share in the government. They will check the unsteadiness of the second.” If the United States were represented by a family, a “father” who thought only of his interests at the expense of his family wouldn’t be considered a very good one.

The delegates to the Constitutional Convention, which stretched from May to September of 1787, were hardly ordinary in their economic standing. In commenting on this economic stacking of the American political apparatus, the political scientist Michael Parenti noted, “The men who got together in Philadelphia to frame the Constitution were financially successful planters, slaveholders, merchants, creditors, bankers and manufacturers. Who else can take four-and-a-half months off to go sit in Philadelphia and write a constitution?”

The Convention itself was a direct response to growing protests and rebellions as a result of widespread corruption, indebtedness and poverty throughout the thirteen states in 1786. It is unsurprising that men of such stations banded together to form a constitution that fragmented the voice of the people in the circumstances that they did, since they had every motivation to do so.

For the first five decades of American politics, the right to vote was mainly predicated on one’s ownership of property. In state governments, during the presidency of George Washington, 94 per cent of the adult population was unable to vote, including 85 per cent of the free adult population. By the 1820s, property qualifications were phased out, but nonetheless, the ability of everyday Americans to enact socially-minded policies was curtailed. African-Americans were denied the right to vote until 1870 (in theory, and until 1965 in practice). Women of all races were denied the vote until 1920, and Native Americans until 1924. “Paupers,” or extremely poor individuals who received public relief, were prohibited from voting in 14 states until 1934. In short, many of the same arguments the American revolutionaries used to justify ousting British rule also applied to the system they created to replace it.

For those Americans who were lucky enough to have their vote count, the system they participated in served to dilute their participation even further. Only the dedicated and wealthy were originally meant to have an impact on government policy. The legislative branch, which ostensibly represents the people and enacts laws with their implicit consent, is divided into the House of Representatives and the Senate. Each state is represented by two senators, regardless of their population, as though the land itself had the capacity to vote. In extreme situations, the Senate allows members representing 16 per cent of the population to outvote those representing 84 per cent of the population. If that wasn’t enough, Senators themselves were not directly elected in the same way as members of the House of Representatives until the advent of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913.

The situation of the executive branch isn’t much better. The Electoral College technically elects the President, rather than the wider electorate, and nothing but a fine prevents the College from selecting a victor who loses the popular vote, as Americans bitterly learned in the 2000 and 2016 presidential elections. If the legislature and executive branches were successfully subjected to greater popular control, their laws would then have to surmount the Supreme Court, whose justices are nominated by the President, confirmed by the Senate, and who may serve for life if they so choose.

In a country that fractures the political power of the wider population, while leaving the private power of capitalism untouched, is it any surprise that economic elites are predominantly the ones who are elected, or who influence politicians to serve their interests before those of the people? They are not anomalous actors, but are receiving the “distinct, permanent share in the government” that was recommended by Hamilton in 1787.

Special Interests

Then there are the interest groups and lobbyists. Individuals can only donate a few thousand dollars to a political candidate, but political action committees can donate unlimited sums, provided they do not coordinate those donations with the candidate themselves. As a result, campaign contributions from a few wealthy donors can easily overwhelm the donations of many more ordinary people, forcing grassroots, anti-capitalist political campaigns to work far harder to achieve the same reach and appeal as those of establishment candidates.

Although candidates must ultimately be elected by the people, they cannot campaign for office without adequate funding, and the people cannot actually force representatives to vote for the policies they desire. As long as interest groups are free to donate to any candidate’s campaign, they can outperform grassroots sources of donations and thereby stalemate the popular vote by co-opting incumbent and would-be officials. Multi-millionaires and billionaires can circumvent this dependence and campaign for office out of their own pockets, serving their economic interests even more directly. In 2016, 48 per cent of representatives and senators were millionaires, compared to five per cent of the U.S. population as a whole.

To sum up, the United States political system, and all liberal democratic systems to some extent, are rife with corruption. It could not be different, given how it was designed and the intentions of its designers. Working within the system means conceding to corruption to some extent. The problem is so thoroughly entrenched that it cannot be uprooted by a Democratic or Republican victor in a presidential election — it requires a critical reassessment of the capitalist dogma that shapes American politics. So long as the means exist for individuals to corrupt politicians, and for politicians to protect the property of the undeserving few, there will not only be a lack of democracy in the United States, but a republic for only minor issues. Regardless of who wins tomorrow’s presidential election, we must not only remember that there are people who are not privileged in society, but also that their interests deserve the same consideration.

This article is part of our Opinions section and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Gauntlet’s editorial board.