Kids like us: How Beverly Cleary projected the voices of generations of children

By Harleen Mundi, April 9, 2021—

When Beverly Cleary published her first book titled Henry Huggins in the 1950s, it served as an answer to a question posed to her by a boy who had a single wish — to be seen. He asked her “where are the books about kids like us?” The kinds of kids who stormed the streets of Portland — or even Calgary, for that matter — with their flamboyant ways and refusal to accept the ordinary. The kids who were always disciplined out of their energy and experienced the very real emotions of guilt, irritation and sadness. From family dynamics to school life, the need to relate to characters with the same chaotic personalities and problems to work through was necessary. It was necessary because it changed the course of literacy children by instilling representation and realism into this genre.

I guess this is where I say that Beverly Cleary’s books were all of that and more. Cleary was indeed one of a kind and I don’t mean that to be cliche or to argue how her artistry put her above and beyond others. I mean to say that she was able to achieve a type of storytelling that was raw and — at that time — was more accepting of children like me than I had ever known. With over 85 million copies of books sold worldwide, Beverly Cleary wrote on behalf of all the Henrys of the world, creating a movement that was all about kids like us.

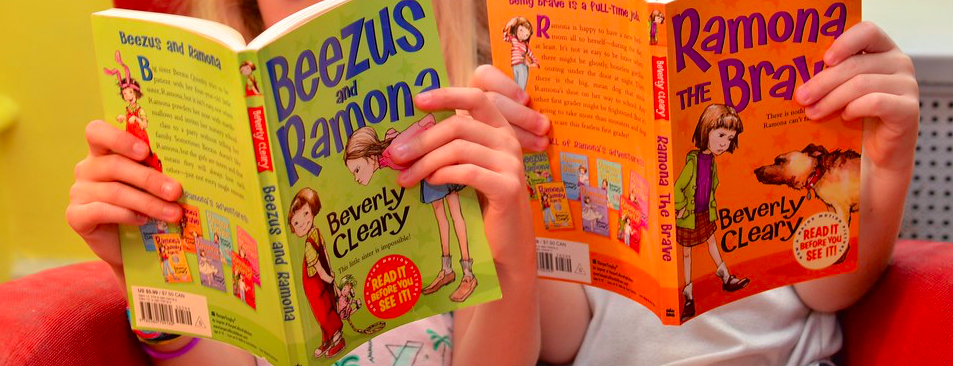

Yet, for me, Cleary’s greatest gift to the world would have to be Ramona Quimby. The loud and sassy Ramona, whose red rainboots and infamous bob-cut hair accompanied me throughout much of my childhood. During Scholastic book fairs, I would always anticipate picking up new copies and growing my Quimby collection, only to carry the volumes around from class to class.

Ramona was the perfect companion in that we were one and the same with our mischievous nature, talkative tendencies and imaginative souls. We navigated life through unconventional ways, found shared hobbies in attaching peculiar names to inanimate objects and pestering our older sisters every opportunity we got. My embarrassment when it came to getting in trouble in class for speaking too much mirrored the Ramona who asked too many questions. On those days when I had to cry out of the shame of being called out, behind closed doors, Cleary was the most gentle with me. She had the patience I needed as a child. More than that, she was different and refreshing. Around the third grade when I was working to improve my handwriting and spelling, she created a Ramona who wrote out her name with only i’s and t’s because of how much she enjoyed the look of the dots on paper — more than the correct spelling of her own name. Or how she painted a picture of the sky which looked nothing like how her sister Beezus described it to actually be.

Such an author blew apart the whole box of what it means to educate children. The box that kids had to fit into in order to avoid punishment or to be considered undisciplined. Rather, Cleary allowed these unlikable qualities to become characteristics of her most important protagonist, because it shed light on the youth that needed the utmost patience, attention and acceptance for who they are.

Beverly Cleary is one of a kind because more than anyone I have known, she got it right. She never diluted the vibrance of her characters so that they would be considered normal. There was a sense of liberation in her narratives that I hadn’t realized until now. This is because Cleary challenged the way society dealt with children — implications that still hold precedence today. With her, kids were able to paint their own realities and carve out their own identities, instead of being moulded into what was expected of them.

I wouldn’t say I have lost Ramona completely. Our loudness still makes appearances at home and I continue to take extra pleasure in pestering my sisters on a daily basis. I also still hold the same vivid imagination I had as a child. However, as I grew older, I inevitably became more introverted and always worked hard to be the perfect kid who would never risk getting in trouble.

Hearing of Cleary’s passing led me back to the series that remains in my personal library. I never had the heart to donate them or stash them away in some vacant box in the basement. Instead, I hoped to save them — as they hold my name scribbled across the covers — because they hold a constant reminder of the kind of child I always was and still hope to be. Now whenever I move to pick them up again, though a much more simmered down and uptight version of myself, I still appreciate her legacy. Not only because these books changed the scope of literacy for youth, but because they represent how crucial it is to allow imperfection and imagination in children. Because of Cleary, kids like us never have to live in the constant fear of being punished for our version of the sky. Instead, we will all learn to paint it a little differently.

This article is part of our Opinions section and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Gauntlet’s editorial board.