CUFF 2021 Reviews: Workhorse Queen and a conversation with director Angela Washko

By Ava Zardynezhad, May 3, 2021—

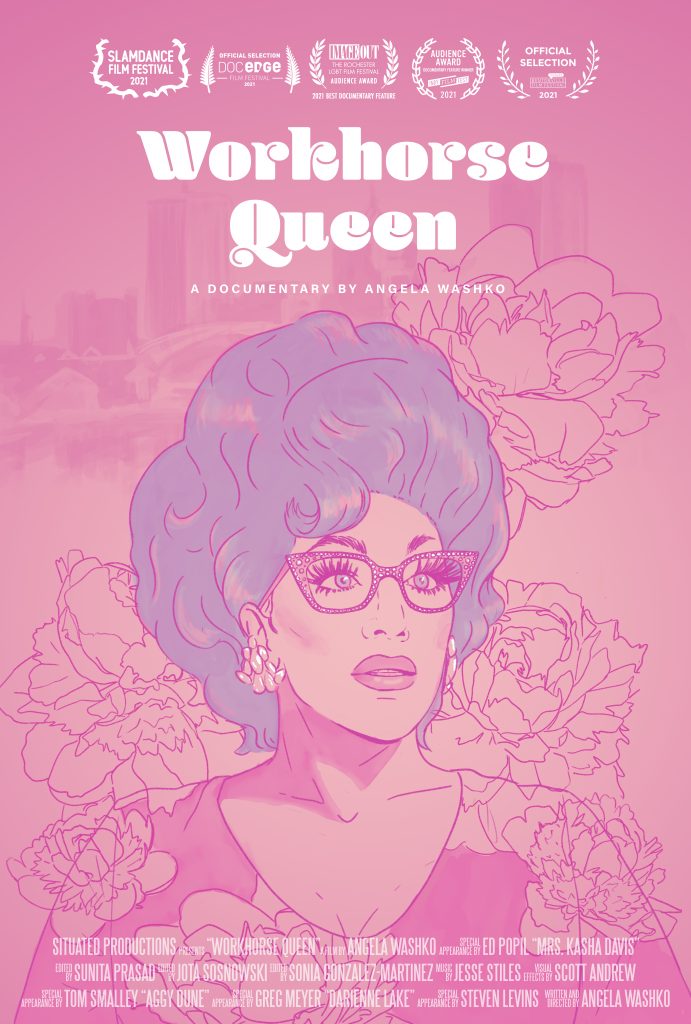

Workhorse Queen is a documentary centring around Mrs. Kasha Davis, who was a contestant on the seventh season of RuPaul’s Drag Race and Ed Popil — the man behind it all. The film follows Popil over a period of approximately three years in his personal life as well as the life and work of Mrs. Kasha Davis as she performs various shows around the United States as well as internationally. It dives into Popil’s early life, his relationship with his parents, his struggles with his sexuality, his marriage and his relationship with his family and of course his relatively late start in drag and the conception of his drag persona — Mrs. Kasha Davis. We get a glimpse into Popil’s 13 year drag journey, years upon years of auditions for RuPaul’s Drag Race as Mrs. Kasha Davis and later, the impact that the show has had on Popil’s personal life as well as the impact it’s had on Mrs. Kasha Davis.

However, what really set this film apart, was how it served as a case study of how media and specifically involvement in a reality television show has impacted the drag community — both the community of queens who have been on the show and the entire drag community that has become divided since the show’s creation.

After watching Workhorse Queen, the Gauntlet sat down for a virtual interview with Director Angela Washko. Washko is a feminist artist and scholar and is currently an Associate Professor of Art at Carnegie Mellon University. According to Washko, her work focuses on “how mainstream media, pop culture and technology impact the way that people understand gender and sexuality.” Workhorse Queen is Washko’s first feature-length documentary, though she is not unfamiliar with the film visual medium.

Washko has long been a fan of RuPaul’s Drag Race. Through all the seasons, she’s “always had a warm place in [her] heart for Mrs. Kasha Davis and a curiosity about her.” The specificity of her name and her persona indicated that “she wants her persona to really be situated in domesticity. She wanted to use this persona to also make an argument for the legitimacy of gay marriage. Because when Mrs. Kashs Davis — the persona — started, gay marriage wan’t legal, so there was a political dimention to [her persona] as well.

Mrs. Kasha Davis is “very focused on performing domestic labour tasks. She often [comes] onto stage with a vacuum, or she’s cooking,” Washko said. “I thought there’s a fine line between caricature, or making fun of someone and honouring them in drag. I really felt that Mrs. Kasha davis fell on the side of really honouring women — particularly of the 50s and 60s — who were in a position to be expected to do an extraordinary amount of domestic labour without being appreciated for it.” So, as a feminist artist, Washko “was interested […] in Mrs. Kasha Davis’ approach to creating this persona as an homage to these women.”

Washko reached out to Popil through email to express her fascination in his story and in “how reality television took [him] from being a full-time telemarketing manager to being a full-time drag queen, attempting to break into the entertainment industry in [his] late 40s,” she explained. Within 15 minutes, Popil wrote back and so Washko was off to Rochester, New York to meet Popil and his husband Steven Levins over breakfast. Soon after, the project was on its way.

However, after starting the project, the community around Popil and Mrs. Kasha Davis became a big focus for Washko.

“Seeing first hand the way that RuPaul’s Drag Race was creating a division within the queens in [Popil’s] community really made it clear that I had to choose either to follow that thread or to ignore it — and I decided that it was interesting and important and so I decided to follow it,” she said.

As a fan, Washko recognizes the service that RuPaul’s Drag Race has done for the community, specifically in terms of how it has changed the culture and the economics of drag. Prior to the popularity of the show, having a full-time career in the entertainment industry as a drag queen was near impossible. Washko also recognizes how amazing it is “that the art form of drag is being celebrated and that kids all over the country can tune into RuPaul’s Drag Race and see these amazing gender non-conforming performers being their authentic selves and not being judged for it — instead being celebrated.” The show has made possible the inclusion of positive queer role models on television and has increased queer and drag representation on mainstream media.

However, she also has criticisms towards the show and finds competitive reality television to be limiting as a form of media.

In the film, we see that it does indeed take a village to do drag. Early on, we’re introduced to Aggy Dune — Mrs. Kasha Davis’ drag sister — and Ambrosia Salad. We learn how these queens helped Popil create Mrs. Kasha Davis and how they have helped Mrs. Kasha Davis’ development and her career in the entertainment industry. These, and many queens in the Rochester community, have been active for over 20 or even 30 years. Yet, despite their long careers, these queens have not yet had a chance at being on RuPaul’s Drag Race themselves. What’s more, their contributions to the success of other queens who do “make it big” go unrecognized way too often.

RuPaul’s Drag Race, as helpful and constructive as it has been for the drag community, has also been harmful in many ways. The show has created a divide in the drag community between queens that have competed on the show and those who have not. The film also hints at a division within the former group, where the contestants that have made it to finalist positions and those who were eliminated earlier also belong to different groups. Workhorse Queen highlighted certain realities of mass media and reality television — media tends to value individuality over community, often denying many individuals involved in the success of others the recognition that they deserve.

“[The] competition reality show format — particularly with Drag Race — can undermine the celebration of the cooperation and collaboration that it takes to sustain drag in any city,” Washko said. “[This] format really prioritizes the celebration of individual icons.

“Sometimes it seems like in order to celebrate these icons as singular there is a kind of erasure of all of the community [and] all of the different hands that it took to get that one person where they are,” she explained. However, she also added that “very recently that’s changed a little on [RuPaul’s] Drag Race. We have gotten to get some insight into the drag houses that have been involved [and] some of the people that have been involved in making the increasingly elaborate costumes that the queens wear on the show.”

Washko also talked about where she thinks this lack of acknowledgement and inclusion stems from.

“Casting [on reality shows] is often tied to ratings and ratings are an evaluation of what a broad public might want from a show like this,” she explained. “In that process, maybe some performers that are more subversive, maybe some performers that are harder to categorize or put into certain boxes, performers who may be trans or non-binary, or drag kings have historically not been as welcome into this reality television version of drag on Drag Race.”

Washko explains that the show and other reality shows like it are not always the most comprehensive reflection of drag communities.

“A lot of the shows that you end up seeing involve the labour of tons of people. Even if it’s individual performances, very frequently those performers are organizing shows [for] other performers,” said Washko. “There’s a lot of people and a lot of community behind an individual person who might end up on a show like RuPaul’s Drag Race.”

Washko also talked about how this translated into other artistic communities and her recent experience as a filmmaker in the film community. While discussing her personal journey and the contributors to her success and career, she emphasized the importance of being present and investing in art communities she’s interested in. After finishing her undergraduate degree, Washko made sure to maintain dialogue with other artists and to seek feedback. She recognized that investing in other artists through organizing shows and events, showing up and supporting her peers created a sense of community and support, where she could rely on the investment of her fellow artists in her time of need in the long run. The connections she made throughout the years following her graduation are “the people who in this filmmaking process [she] turned to.” People who were able to help her with securing funding for this project, finding a workspace and recruiting editors.

Washko emphasized how important it is “as an artist to work against the narrative of the ‘individual genius’, […] toiling and suffering for their art.” She thinks this mindset reflects privileged people with money to spare. For her, figuring out what artists she wants to be in conversation with, where those conversations are happening and how she can contribute has been essential to her success.

“I made Workhorse Queen, initially, still relying on my art community and the networks that I’ve established,” she said. Making this film also required the skills and talents of many outside of the communities that Washko had established herself in. Immediately after starting work with the Supervising Editor of Workhorse Queen, Sunita Prasad, Prasad told Washko she would “need more people to be involved in the post production process.”

In her search for editors and colourists, Washko turned to other communities such as the Karen Schmear Diversity in the Editing Room Program and Brown Girls Doc Mafia. She looked for “people that would really connect to the story of the film [and] who would really understand the types of experiences that are discussed in the film in a more nuanced way.”

That being said, Washko also explained that the challenge is that filmmaking requires so many people and having more long-form interviews and conversations were difficult due to the current clickbait media landscape.

“People want five minutes — fast — with whomever is the centre of the thing,” This, unfortunately, creates a media landscape where the focus shifts from cooperation to competition.

Workhorse Queen also explored Popil’s life and Mrs. Kasha Davis’ career after her time on RuPaul’s Drag Race. Following Mrs. Kasha Davis, we see how she’s ventured compared to other queens whose journey on the show lasted longer. We see Popil struggling with alcoholism after the high of post-season promotions had passed, we learn about the challenges he had to face in pursuing drag as a full-time career and we witness his efforts on his — and Mrs. Kasha Davis’ — road to recovery. We learn about Mrs. Kasha Davis’ one-woman show — which is a narrative of Popil’s life — and through it, we learn about their dedication to storytelling.

Popil’s love for storytelling meant that Washko had to find a balance between his voice and hers in the film.

“I’ve always been critical of the way that documentaries tend towards this ‘objective fact-based’ point of view. Subjectivity of filmmakers is often suppressed or erased in order to present this sort of factual authority that documentary often presents itself with,” Washko explained. Before being a documentary, Workhorse Queen is a portrait — the story of an individual and his community — and Washko was adamant on presenting it as such. It was important to her to balance her own creative voice with that of Popils, ensuring that he can tell his story the way he wants it to be told and that through it, Washko can take a deep dive into the discussions that she felt were appropriate and necessary to have in this film.

Washko said that Mrs. Kasha Davis had her own ideas of what the film was going to be and that she wanted to make sure that certain things — specifically when it came to how she was presented — were included. However, to Washko, honesty and authenticity was important.

“One of the things that I feel like I can offer, that is unique to the mainstream media, that we’ve seen about drag so far — particularly RuPaul’s Drag Race drag queens — is peeling back some of the performance and allowing people in and getting a view into what the labour behind maintaining this career and this persona looks like,” Washko said. It was important for her to capture “what [Popil’s] domestic life feels like, [or] what does it feel like on the weeks when [he doesn’t have] bookings.”

At times, this film did capture how Mrs. Kasha Davis was trying to present a certain narrative. One of her future goals is to be included on RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars and in order to do that, she put a lot of value into engaging on social media and seemed to present a version of herself that she thought would be appealing to the public eye. The irony that this film shows was that queens get involved in drag because it is a freeing experience. It is a way through which they can be their most authentic self — drag is often a celebration of their sexuality, their personhood and their essence. However, because of the competitive culture that reality shows such as RuPaul’s Drag Race have created, most queens succumb to pretence. Drag becomes less of a freeing form of self expression and more about putting on a show — pun intended. The drag culture that reality television and media has fabricated forces queens to fit a certain criteria and a predetermined mold if they want to be included and if they want to survive in this incredibly competitive environment. Washko shows that perfectly in this documentary and goes beyond the makeup and the pretense to dissect and present the fears, pressures and factors that motivate queens and decide their success in the drag community.

Before watching the film, most promotional articles said that Workhorse Queen was a “must-watch for fans of RuPaul’s Drag Race.” About this, Washko says name-dropping Drag Race helps bring fan viewership to a press outlet. However, She doesn’t want the takeaway of this film to be a puff-piece about how great Drag Race or how great Mrs. Kasha Davis is.

“[Workhorse Queen] is a portrait of someone who’s gone through the experience of going on to this reality television show and having their life completely transformed by it,” Washko said. “For me, I hope that viewers become interested in it broadly because of how it is a portrait of this unique contemporary media landscape we’re in right now where someone can go from being a full-time telemarketing manager in the suburbs of a small city, apply to be on a reality television show focused on drag, […] go through this reality television show experience and come out the other end, leaving his full-time job to pursue celebrity stardom at nearly the age of fifty.

“This phenomenon [of] seeing what reality television does to subversive subcultures is important as well,” Washko continued. “I hope that I’ve approached the subject with a certain amount of complexity and generosity and openness that resonate across perspectives.”

Washko’s vision, Popil’s truth and the hard work and mastery of an entire community dedicated to making this film has made Workhorse Queen a must-watch for everyone. This is a film that everyone should be watching and a discussion everyone should be having, because if not specific to drag culture and the drag community, these are realities of how societal forces, specifically mass media, change the fabric of our communities.