See you at the premiere: The deromanticization of a life in the arts

By Riley Stovka, February 1 2022—

Ross Smith began writing as a kid in 1979. In 1984, a comedy sketch written by Smith ran on British television. His first movie, The Revenge of Billy the Kid, debuted in 1992 and his first play was staged in 1995. His biggest hit in cinema came with the 2005 release of The Adventures of Greyfriars Bobby, based on the true story of a 19th century Skye Terrier, known for guarding the grave of its deceased owner. In 2010, One Small Step, debuted on the stage, quickly earning praise as the British play of the year.

With so many accolades and career credits to rival other well-known writers of his generation, Smith’s talents would have surely propelled him to literary stardom.

However, oddly enough, that is not the case. Firstly, Smith uses pen names — Richard Mathews for his film credits and David Hastings for stage — so perhaps you’d be forgiven if you have not heard of him even if you have heard of his works. Second, writers are often the forgotten talents behind the art they create, favoured behind the actors and directors that take the credit for translating the artistically crafted words from paper to screen. Third, and most importantly, there is an endemic mystification of artistic value that more often than not, leaves behind those that practise such work.

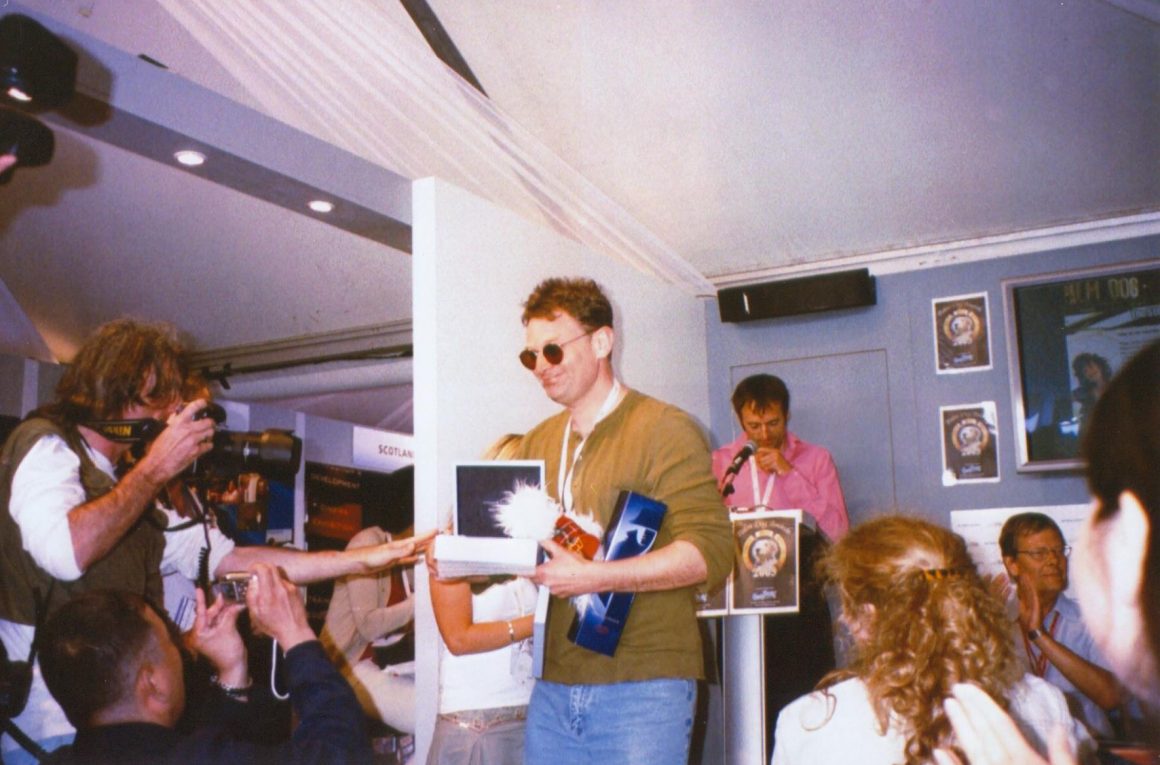

Smith’s newest piece of writing, a memoir, insider’s guide and self-help book, titled See You at the Premiere: Life at the Arse End of Showbiz, chronicles the last two decades of Smith’s life, spanning from Los Angeles to London, from Washington D.C. to the Cannes Film Festival, brimming with stories from Smith’s lifelong career in the arts. It functions simultaneously as a writing handbook and a warning to all those who wish to pursue the same career.

At the heart of Smith’s book is the demystification of the perceived glamour of a career in the arts, revealing the crushing day-to-day artistic, financial and emotional strain that a vast majority of creative people go through. The book also serves to function as a cultural critique on society’s fixation with showbusiness, while also questioning and celebrating creative passion.

For Smith, the problem with the allure of a life and career in creative writing can be boiled down to what is offered by the artist compared to what is given.

“It’s a question few of us want to be confronted with because all of us, regardless of our experience, want to believe we will monetize our talent. The harsh reality is the majority of us won’t,” says Smith.

The lack of respectable wage is nothing new in the field of arts and should not come as a surprise to anyone — however, the answer as to why may shock some.

“One reason [why we can’t earn a respectable wage] is our own fault — we’re all too willing to be seduced into working for free in exchange for the promise of credit for our resume,” said Smith, “People will always hire you if you work for free or for little money. So, after a few bits of work experience, [you] need to stand your ground.”

The arts as an industry is overpopulated with talent desperate to get credit to their name and polish up their resume. The sad reality is, the table is packed and not all will get to eat.

For a professional like Smith, it’s best to make sense of the problem with the help of a metaphor.

“Imagine a closed door. Every artist stands on either one side of the door or the other. If you’re on that side of the door — if you’re ‘successful’ — you’ll have opportunities. If you’re on this side of the door, where the vast majority of us are — working out of the arse end of showbiz — most of your projects won’t happen.”

However, the twist of the knife never stops — even if you are on that coveted side of the door, it isn’t a guaranteed passport to fame and fortune.

“[There are] gazillions of creative people who had strings of projects commissioned and then things just stopped, usually through no fault of their own. Establishing yourself is extremely difficult, so is maintaining your career over a lifetime,” says Smith.

Most artists are confronted with disappointment daily. It is the daily occupational hazard, a workplace safety incident that doesn’t leave you bruised or broken, but still stings nonetheless. Abilities are questioned, confidences are shaken and the drive to persevere throughout is tested almost hourly. There is perhaps no more challenging profession than a career in the arts when it comes to your work being questioned. The judgment based upon your work is almost entirely subjective, there is no definite measure to how good or bad your work may be. It is one of the factors that sets a person working in the arts apart from almost any other

profession.

It is freelance. There is no such thing as tenured or prolonged contracted work as a creative person — it is constantly paycheck to paycheck. Even those who do hack it in the industry, those deified by their audiences and respected by their peers, can just as easily run aground — for example, Ross Smith.

“I’m being brutally honest, my career has stagnated. Credits weren’t mounting up as much as I’d expected. It happens, especially in a business as precarious as the arts. A career isn’t a job with regular work and pay, it’s up and down,” admits Smith.

So why not quit? Why not leave a life spent in creativity behind for more stable work and a steady income? Why not give up on the stress and constant disappointment? For Smith, the answer is simple.

“Quitting is something I never considered for a moment during the first half of my career. Because, as with every artist, I was blinded by ambition. Not for a heartbeat did I think I’d fail. In more recent years, I’ve decided not to quit because, frankly, there is nothing else I can do, […] I have to persevere with writing because it’s now too late to change.”

For the past couple of years, Smith has transitioned into a career as a non-fiction writer. He has spent the latter half of his career at BBC Radio 2, writing and researching for almost 100 programmes and conducting interviews with massive Hollywood stars like Matthew McConaughy, Keanu Reeves and Bruce Willis.

But, to those for whom it’s not too late to change, those who are young enough to learn something new or pursue another career avenue, Smith has some advice.

“Throughout the first few years of your career, ask yourself, ‘am I still enjoying this?’ If the answer is no, the struggle and the meager rewards aren’t worth the effort and maybe you should quit. Regardless of whether you’re in the arts or not, ask yourself, ‘when I’m old and looking back on my life, will I appreciate what I have achieved?’ If the answer is no, change things.”

With all the uncertainty that life in the arts creates, the moment or moments where you can step back and admire your work or bask in your achievements are few and far between. For many, they may never come, but if or when they do, they can leave those who spend their lives playing with words speechless.

Smith recalls the moment that brought him the most fulfilment as a creator, the moment that he knew he had made it. “ [When Greyfriars Bobby] was released in 2005, as the credits rolled, so did my tears. It wasn’t the emotional story as such, it was what the film meant to me. I felt like an athlete winning Olympic gold. My tears were relief at achieving something I’d been striving for since I began writing back in 1979.”

Smith’s book challenges those who wish to pursue a career in the arts to evaluate themselves and their plans. It is critical of an industry Smith has spent his entire life in, but it also shows the gratification that comes from achieving a childhood dream.

With all the crushing lows that come attached to a life in the arts, there are also those sweet, euphoric highs — the type of which you’d never forget.

For Smith, that came in Washington D.C. His play, One Small Step, was being performed at the Kennedy Centre for the Performing Arts. In front of a sold-out crowd, Smith’s play received a raucous standing-ovation that reverberated throughout the Kennedy Centre’s hallowed halls. The celebration spilt out onto the National Mall as Smith and his cohorts sang “Born in the USA,” as they drunkenly gallivanted around the US capital until 4 a.m.

“I’d spent my entire life in showbusiness and that night, I felt my talent had finally been vindicated. It reminded me why that 16-year-old kid got into showbusiness back in 1979.”