Stanford University health psychology expert talks approaching stress at university

By Scott Strasser, September 13 2016 —

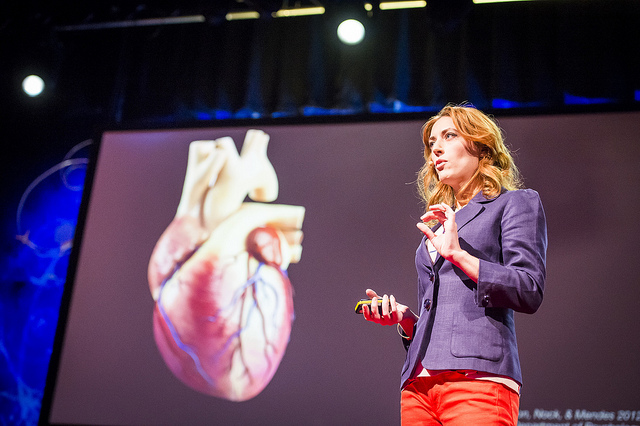

Kelly McGonigal is a health psychologist and professor at the Stanford University Graduate School of Business. An expert on stress resilience, McGonigal gave the keynote speech at the University of Calgary’s Orientation Week induction ceremony on September 6. McGonigal is also known for her TED Talk “How to Make Stress Your Friend,” which boasts almost four million views on YouTube. The Gauntlet spoke with McGonigal about why stress can be a good thing and how students should approach handling stress in university.

Gauntlet: To start, could you give a rundown of what your keynote speech was about and what your main message was to first-year students at the U of C?

McGonigal: I think the main message was that a meaningful life is going to involve stress and challenges, but we can adopt a mindset that lets us harness that stress and transform even adversity into things we value, like community, strength, growth and learning.

I tried to share a little bit of the science that shows that the way we think about stress and the way we react to it can help us avoid some of the things we’re so terrified of — that sense that stress will completely paralyze or overwhelm us.

G: So, the essence of the speech was that stress doesn’t have to be a bad thing?

M: Yes, and that’s true even for the types of stress we would love to avoid. Sometimes we think about “good” stress, like the excitement of being on the field in an athletic competition and winning, or the stress of getting a challenging new job that you’re really excited about. Bad stress is then all the stuff we don’t want — it’s the rejection, the failure, the uncertainty, the things that are painful.

Of course it’s not always going to be a fun thing, but it‘s useful and we can become good at stress in a way that makes good use of what’s positive about it.

G: In your TED Talk, you referenced a study that found stress was physically harmful in a biological sense only when it was viewed as a bad thing.

M: This was a study that came out about five years ago that blew my mind when I saw it. It found that people who had a lot of stress in their lives were at an increased risk of dying in the next decade, but only if they said at the beginning of the study that they thought stress was really harmful for their health. People who had stressful lives but didn’t view their stress as harmful for their health were the most likely to still be alive.

The researchers were claiming that people were dying not from stress, but from this powerful combination of experiencing a lot of stress and thinking that the stress was harmful. There was something about that combination that was toxic.

G: But how do we convince ourselves to change the way we view stress?

M: The mindset that seems to be important is one I call “holding opposites.” You don’t need to convince yourself that every tragedy in the world has a silver lining or that you love how it feels when you’re anxious or overwhelmed. The mindset seems to be to accept that these things are a part of life. And there is something good in you that is waiting to be unleashed in these difficult moments. The types of “mindset resets” that have been shown to be very effective for college students are to start to view your stress as energy. You can reframe almost any physical sign of stress as a sign that you’ve got energy and adrenaline going. Your body recognizes this is a moment that matters. That energy can help you, even if we don’t like how it feels.

G: If stress isn’t bad, should we still do things like yoga, meditation and exercise to try and reduce it?

M: So you might not know this but I actually am a meditation researcher and a yoga teacher. When you do these activities, what you discover is that it’s quite effective in just turning off your brain and inducing a kind of peace that will stick with you forever. These kinds of techniques tend to give us a different way of relating to our thoughts so that we have more freedom in the ways that we deal with our worries. Or they might give us a better sense of our ability to tolerate discomfort.

When I teach yoga, I think about it, and as I teach fitness I think about exercise as, ‘it’s okay if your heart is pounding, it’s okay if you are struggling to breathe a little bit, it’s okay if you are sweating under the pressure — this is what it means to be alive.

G: Your research also talks a lot about the biological effects related to stress management. What can you say about the biology behind how we view stress?

M: Most people have heard of the fight or flight response. When you’re stressed out you enter this mode of irrational thinking or you become aggressive and hostile and you look for ways to run away and protect yourself. Most people think that is the only physiological response humans have to stress, which is not true.

When it comes to embracing the biology of stress, you can actually get the [biological response] you want by choosing the mindset that goes along with each response. Stress is a psychological response that has biological outcomes. If you want to change your stress response, just changing the way you’re thinking about the stress can completely transform what’s happening in your body. And that can transform what you’re capable of in terms of responding to it.

Edited for clarity and brevity