Reflecting on The Bows’ Gnoul Exhibition: On police brutality and the experience of Blackness

By Aymen Sherwani, Sheroog Kubur, July 27 2022—

From June 17 to July 9, 2022, The Bows exhibited Gnoul: A Benefit Exhibition for the Family of Latjor Tuel, who died at the hands of police violence in Calgary earlier in February — the focal point of this project being his daughter and model Nyalingat Latjor, shot by photographer Michèle Bygodt. Tragically, the project was conceptualized before his death and was initially aimed at encapsulating the dehumanization of Black people — how their existence and subsequent treatment has historically been whittled down to physical appearance.

“When we were talking about bringing attention to Black oppression through art during the George Floyd rallies, I never thought I would be going through the same thing that his own daughter had to go through,” said Latjor in a statement provided to the Gauntlet. “We wanted to explore the concept of Black bodies, the objectification of Black bodies, but also the beauty of Black bodies as well. When I was shooting I was living through my Black experience and wanted to show my truth — the truth of living in a Black body in a Eurocentric world through art.”

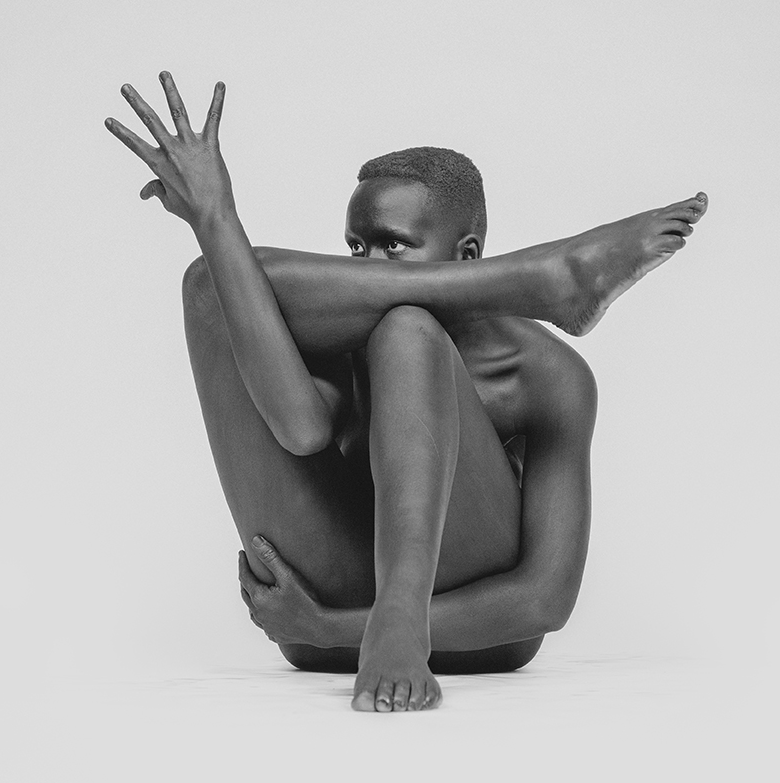

The exhibit itself was modest in size, displaying five of the six photos in the main area of The Bows Gallery, but the photos were quite the opposite. Each one was emotionally evocative in its own way, making the exhibit as a whole quite overwhelming. The pieces were all composed of Latjor, contorting herself in superhuman positions, creating angles and shapes that were cold and distant while maintaining a degree of intimacy. The camera positioning was controlled and steady, making it feel like it was an objective representation of the model. The positions of the model mirrored that sentiment through expertly-done poses and intricate detailing. The simplicity of the camera captured the complexity of the model, working together to create a piece that was both convoluted and easy to digest.

The inspiration behind the photos was the representation of Black people while rejecting the idea of Black people as the “other.” As to how the photos display Blackness, it’s difficult to clearly define. The photos are in a greyscale, stripping away contemporary ideas of race and replacing them with colourless representations of being Black — the spectator can clearly tell the model has dark skin, but her Blackness is represented through things like her hair texture and facial features. In representing Blackness this way, it shatters the instinct to spectacularize Black people. The model is not a vision of something to be admonished or turned into a hero, she is simply a Black woman representing herself as she wants to be seen.

“I got angry hearing people calling Black people “bodies,”” said Bygodt, explaining why she named the exhibit Gnoul — which roughly translates to body in Fang, her mother’s native language originating from Gabon. “A body is just a structure, a skeleton, so I don’t agree with people just using the term body to define someone else, because then it means you’re removing their humanity — we’re not just bodies.”

The presentation of Latjor’s body is also a curious detail, as she is rarely seen as a whole entity. She contorts herself in such a way so that parts of herself are always hidden from the camera while other parts are brazenly displayed, such as the near perfect 90 degree angles of her legs and arms obscuring the bottom half of her face. This creates a juxtaposition of both intimacy and distance for the viewer, who finds themselves face-to-face with how she chooses to present herself — we only see as much as she wants us to see. It’s empowering to see such a straightforward level of control coming from a Black woman, whose body has been transformed into a political entity.

Each individual photo tells its own story just as much as the exhibit itself. While discussing the art, it is impossible to ignore the circumstances surrounding its exhibition. This makes the work simultaneously apolitical and extremely political — it rejected the politicization of Blackness by subverting what art created by Black people is expected to be but became politicized through the actions of the police system. And thus, the exhibit has perfectly displayed the Black experience. Blackness isn’t inherently controversial or contentious but will always be turned into such because of the world we live in. It’s both empowering and disheartening, celebrated and condemned. Gnoul is the Black experience, as much as it was never meant to be.

Calgary police shot and killed Latjor Tuel — a Sudanese immigrant that, according to his family, was struggling with the trauma of being a former child soldier living with post-traumatic stress disorder PTSD. What is incredibly striking is that officers resorted to attacking and provoking him with police dogs, rather than prioritizing de-escalation measures and due process. The community affirms that Tuel was sitting and waiting for the bus when the police confronted and fired on him, but had this been a White man running around Calgary with a machete — who also happened to be the son of a serving police officer — you’ll find that they’ll be given due process and likely granted bail.

There’s an all-too-common saying out there that life imitates art, but in this case, this art is a living and breathing manifestation that co-exists alongside the lives it attempts to portray. There is nothing one can feel other than anger and heartbreak when understanding that Bygodt and Latjor dove into this project seeking to advocate against police violence after the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, but found themselves knee-deep in the systemic violence they are seeking to advocate against.

“It was a way for me to emotionally deal with maybe everything that happened. You have anger, and you don’t know what to do with it, and you see all these videos, and it’s just kind of terrible,” said Bygodt. “When I started, I didn’t even know what I was doing, I just needed to explore this thing and reminding everyone that we’re all human beings — not just bodies — so when I learned the news, I never thought that the person in my photos ends up living the same situation that we were trying to denounce.”

To add insult to injury, those that attended the opening night of the exhibit noticed a police officer parked directly across from The Bows — not in solidarity, but for surveillance.

“On the opening night, I think a very different community came out to support this fundraiser and overall it was a beautiful and joyous night,” said Godfre Leung, the curator of this exhibit, noting the overwhelming support shown by the South Sudanese community to which the Latjor family belongs. “The one thing that did happen was that the police showed up and were parked just outside on the street — that officer never left the car but my sense is that they serially target and harass the community members who came to this event.”

“Nya’s father was murdered but they still have to be here to terrorize people? I don’t know what else to say beyond that because it was such a gutting moment,” he added.

To have the police continue to harass Latjor and come to the opening night of her exhibit which seeks to condemn police brutality — and raise funds for her family — is nothing more than repulsive. It is a harrowing reminder that Black people in North America cannot exist without their bodies, actions and existence being policed — a reminder that hatred is rooted in objectification and the unwillingness to see someone as a person, but rather, something to fear.

“I don’t want people to forget about my father Latjor Kuony Tuel, nor the Calgary Police Department to forget how horribly they took his life and the state they left him in after they killed him,” concluded Latjor. “I have my mouth open, and at full volume with no apologies. Though I’m exhausted — and some days feel defeated — I continue to speak loudly about my father Latjor, the struggles faced by Black and African people and on Canada’s rug sweeping of its rampant systemic racism issues.”

To learn more about Gnoul: A Benefit Exhibition for the Family of Latjor Tuel, visit The Bows’ website.