Postdoc at the Hotchkiss Brain Institute finds empathy is regulated by oxytocin

By Freeha Anjum, August 25 2023—

Empathy means feeling how someone else feels — essentially placing ourselves in their shoes. This gives us the ability to form close social relationships, provide others with support and make moral decisions in our everyday lives. Aside from this, empathy also helps organisms avoid danger by allowing them to feel each other’s fear — and some argue this is the true biological reason that we are able to empathize with others in the first place.

In an interview with the Gauntlet, Dr. Ibukun Akinrinade, a postdoc at the Hotchkiss Brain Institute (HBI) at the University of Calgary, discussed her research linking empathy to oxytocin in zebrafish. She believes this could be a stepping stone towards understanding more about empathy in humans.

Akinrinade explains that empathy is a natural instinct in humans and other complex organisms, but scientists do not know how far back in evolution this instinct is presented. This is what Akrinade’s team hoped to find out.

“When we see people running on the street, we tend to run with them. It’s an innate behaviour — something we do without even thinking about it. This seems to be linked to survival because we want to run away from that stimulus that we are seeing […] This behaviour also happens in other organisms, especially mammalian species like mice and rats. It goes on towards animals like birds. We wanted to see how far in evolutionary time this behaviour is represented because since it’s linked to survival, we hypothesize that it should be seen even in simpler organisms.”

“We chose zebrafish as a model because they are evolutionarily distant from humans, but have over 75 per cent similarity of genetic make-up to humans,” Akinrinade explained.

From 2015 to 2023, Akinrinade’s team set out to test if this simpler organism has a sense of empathy with its peers. They used a substance released by injured zebrafish in order to elicit fear responses in other zebrafish and then studied the behaviours. They found that zebrafish display behaviours similar to more complex organisms.

“For my experiment, I used a substance released by the zebrafish to trigger a fearful response in other zebrafish to alert them that there is danger ahead,” Akrinade says. When talking about the results, she explains “Zebrafish could also perform those behaviours. So when they see their siblings scared, they also become scared.”

Akinrinade’s lab was able to link this response to a component of the brain that regulates the behaviour.

“From the results that we saw, when the zebrafish is scared, they do erratic movements,” said Akinrinade. “They run around and then they freeze. We found that the freezing aspect is what is being regulated by oxytocin.”

She therefore confirms that the hormone plays a part in the conserved behaviour of these fish.

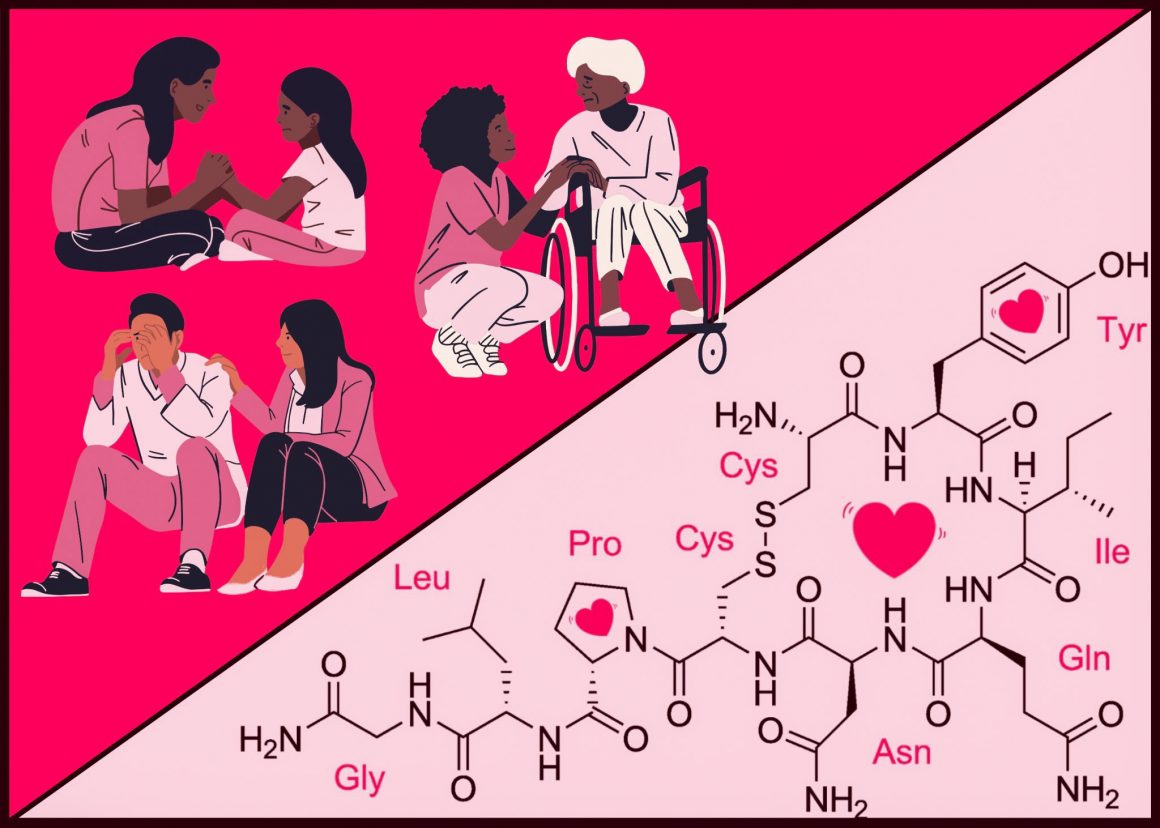

Oxytocin is commonly known as the “love hormone” and plays a critical role in lactation and baby delivery, among many other functions. Akinrinade explained that from the literature, we know oxytocin has been implicated in different social behaviours, but little is known about its role in zebrafish. She believes that understanding which behaviours are regulated by oxytocin in zebrafish can be a starting point for many future studies.

“It’s not like all social behaviour is being regulated by oxytocin — it’s actually specific social behaviours,” said Akinrinade.

Given that zebrafish are simpler, social creatures with a high genetic similarity to humans, Akinrinade believes that understanding these mechanisms in zebrafish can allow for the understanding of these mechanisms in humans too.

“We can easily dissect the neural regulators of empathy, and so we can easily apply the results we see from our studies in zebrafish to humans,” said Akinrinade.

When asked about the benefit of understanding these mechanisms in humans, Akinrinade continued that understanding this hormone’s role in the body could help create better pharmaceutical drugs to treat mental health disorders such as social anxiety. However, there are some barriers to cross, as Akinrinade talks about the biggest difference between these studies in zebrafish and humans.

“For humans, we have the ability to not just feel what the other person feels, but to know how the other person feels, basically reading the other person’s mind to know what they’re thinking about,” she said. “The limitations for zebrafish is that we’ve been able to show that zebrafish can feel what another zebrafish feels, but we have not been able to show that a zebrafish knows what the other zebrafish feels.”

Akinrinade’s next step is to understand how generalized this oxytocinergic regulation of empathy is. After looking at one substance released by the zebrafish, the team has some further questions about their findings.

“There are other cues in the environment that depict fearful responses, right? So is it all these cues that oxytocin regulates?” she said.

Although the project has been a long one, Akinrinade seems hopeful for the implications of its findings thus far.

For more information about Dr. Ibukun Akinrinade’s research findings, visit Journal Science.