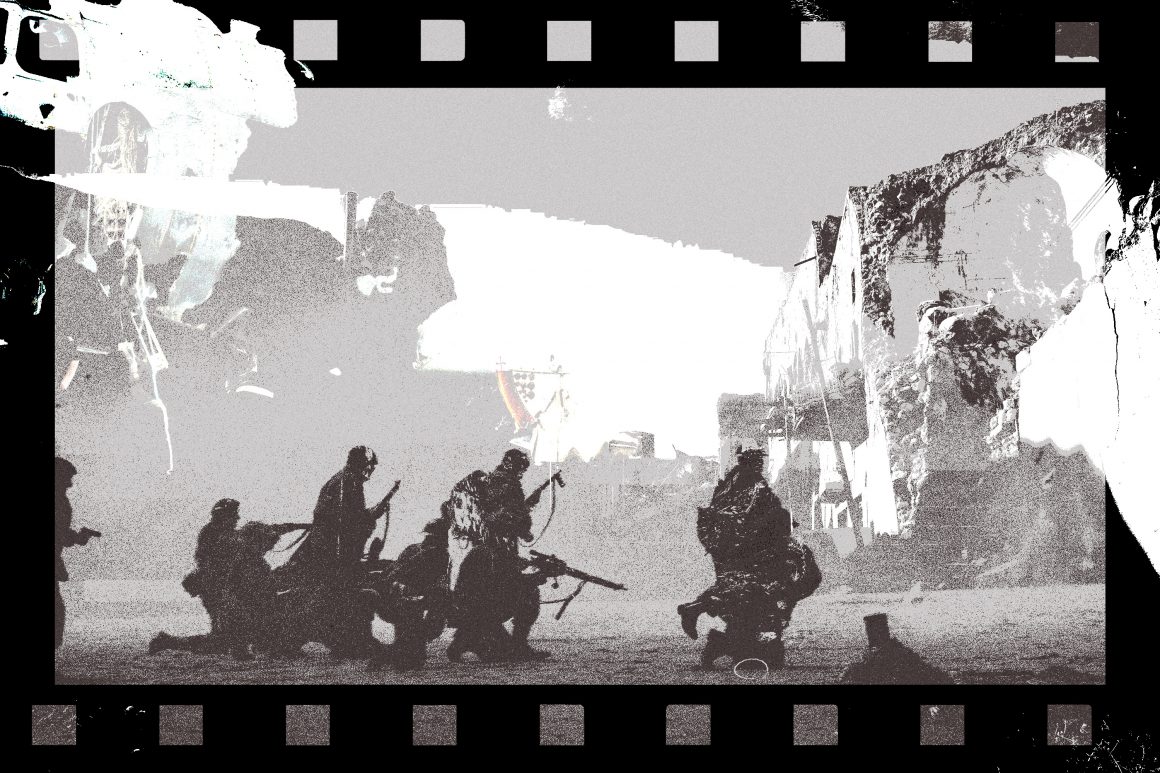

When movies glorify war

By Sheroog Kubur, September 1 2023—

Film is invasive — we as an audience are sat before these people who don’t know they’re watching, witnessing a story unfold and are ideally constantly entertained. The more the film tries to depict human stories, the murkier the film message of the film becomes. What was the director’s intention while depicting these horrific people doing these horrific things? What did they want the audience to feel? What are we supposed to think?

To glorify something is to present it in a good light as if the subject is inviting awe or wonder towards the audience. Films glorify their subject matter all the time for different reasons — something like Ocean’s Eleven, a film about 11 criminals coming together to help their ex-convict friend, glorifies acts like performing a heist, but that’s on the backburner compared to how cool every character is. In fact, organized crime is glorified because they chose to center the people behind the crime, and every single one of them is objectively, pretty cool.

Organized crime isn’t something that can be easily done, so why Ocean’s Eleven may glorify committing a heist, there isn’t very much incentive to do one yourself. Glorification becomes tricky when it’s glorifying something that has a much more tangible impact on humanity, like war.

American films about war shamelessly land on the glorification of war because there is a market for it. The US Department of Defense has been backing films for more than 100 years at this point, directing funding and giving resources to filmmakers and studios for favourable depictions of the US military. A well-known culprit of this is a good chunk of superhero movies, including films like Iron-Man, Man of Steel and Captain America: The Winter Soldier.

These movies are shameless — presenting military personnel and badass characters that are working with the good guys, using expensive military equipment to fight the good fight and never doubting the morality of the good guys.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, there are movies that have no desire to show the scenic intensity of conflict or have epic slow-motion shots of the soldiers coming to save the day. A film like 1917 (2019) and All Is Quiet on the Western Front (2022) are brazen anti-war films — depicting the transition of these characters from ardent soldiers ready to fight for their country into traumatized, deeply troubled young men. There is no question that war is a horrific tale that leaves no winners, despite what these other films may suggest.

A culturally relevant case study is the newly released Oppenheimer (2023) which follows the creator of the atomic bomb. Thanks to Oppenheimer’s spineless morality, there has been debate as to whether or not the film was glorifying his creation. There’s no moment where any characters outright condemn his actions and he doesn’t explicitly state whether or not he regrets his creation. The film does make a spectacle of the detonation of the bomb, although that spectacle becomes the source of Oppenheimer’s moral anguish later in the film. It tows the line between depicting his story and the spectacle of the bomb.

A film doesn’t need to outright state its stance on an issue to make that its subject. Films that have the delicate balance of glorifying the subject matter and critiquing it are a testament to the skill of the filmmaker, although that doesn’t mean there is no shortage of films that opt for shameless glorification. When watching these films, don’t forget to ask yourself if you’re watching the good guys beat the bad guys or a collection of complex tales woven together.

This article is a part of our Opinions section and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Gauntlet editorial board.