The City of Calgary’s Transit History

By Mariah Wilson, May 10 2018 —

Public transit is a vital part of any urban environment. It can define a city through its integration of public art, like in the underground tunnels of Stockholm, or its impressive speed, like the blazing maglev train in Shanghai. Whether people find their city’s public transit charming or down-right frustrating, it provides them with the mobility and accessibility they need to navigate the places where they work and live.

But public transit is much more than simply the bus routes and LRT lines that we interact with everyday. Through the city’s 109-year history of public transportation, we can observe the ways we get around and the structure of our city. Here’s a brief history of Calgary’s transit development over time.

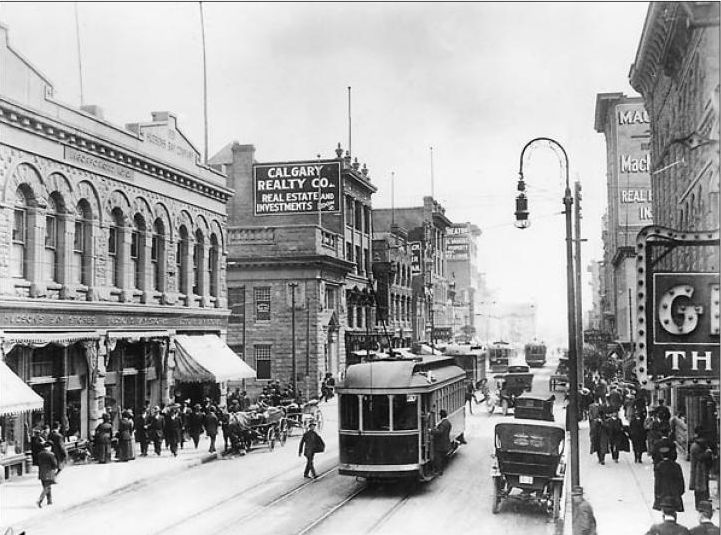

Streetcars

In 1909, the city began operating 12 streetcars to provide its growing number of residents with a means of transportation, as most working-class Calgarians couldn’t afford personal vehicles. It debuted as the first skyscraper was built in Calgary — the six-storey Grain Exchange on First St. SW. Even from the early 20th century, it’s evident how the corporate development of the downtown core influenced the urban form of public space and public amenities. The creation of these streetcars was the first step in Calgary becoming a truly modern city.

The streetcar system was dubbed the “Calgary Electric Railway” and had a terminal point at the Stampede grounds. It wouldn’t be renamed “Calgary Transit System” until 1946 when diesel and electric-powered buses became more popular. At this junction, transit served communities as far north as Tuxedo Park and as far west as Parkdale.

A 1998 PBS documentary titled Calgary Remembered features interviews with residents who grew up with the streetcars, warmly recounting the joy and amusement they experienced from the new mode of transportation. One resident remembers holding onto the back of one of the streetcars while riding his bike. Another remembers splitting their streetcar ticket in half to take two rides when in economic straits.

Communities such as Marda Loop and Bowness would not have developed into their current form without the influence of the streetcar system. Marda Loop was the turnaround point for the Marda line. Through this, it became a thriving core for urban life and street activity. The former town of Bowness, on the other hand, was not annexed into Calgary until the 1960s. At the time, it received streetcar service in return for building a steel bridge and giving the city some of its land, which later became Bowness Park. James Hextall, the landowner of Bowness, wanted to develop it into a community where “the wealthy could enjoy the pleasures of a large country home on the banks of Bow River.” Bowness has since become a thriving community within Calgary. Today, the steel bridge that carried streetcars over the Bow River between downtown Calgary and Bowness is named the James Hextall Bridge and is used for pedestrian and bicycle traffic.

Even though Calgary’s last streetcar retired from official public transit use in 1950, you can still ride it — the restored trolley now operates at Heritage Park where it shuttles park visitors.

Buses

Calgary first started offering a bus service in 1932 by introducing gas-fuelled buses to connect communities that didn’t have access to streetcars. During the 1940s, electric buses and electric trolley buses were added to the mix. These buses were eventually replaced by diesel buses between 1950 and 1975, as the city grew by half-a-million people and needed a more reliable and economically feasible service. Our current BRT system and 305 route are considered the replacements for the Blue Arrow service that was introduced in 1972, providing limited-stop routes for quicker service.

Over the past few decades, Calgary Transit’s bus service has seen its share of controversy, strikes and milestones. The Amalgamated Transit Union reported that in 1961, employees of the Calgary Transit System were forced to “engage in one of the longest municipal transit strikes in Canadian history” — a 37-day affair. The union referred to then-mayor Harry Hays as an “arch conservative” for running on a campaign that would reduce the city’s transit expenses during a period of high inflation. When the transit workers asked for an eight-per-cent wage increase to reflect the growing inflation rates, Hays responded, “I’ll see you in Hell before you get another penny.” A resolution was finally reached when the city agreed to a nine-cent wage increase for all transit employees.

At the tail end of the 1960s, post-secondary students took to the streets of downtown Calgary to protest increased ridership fees imposed by Calgary Transit. Their November 1968 protest demonstrated the students’ dissatisfaction with the city’s decision and the need for affordable ways to get around the city.

CTrain

On May 25, 1981, Calgary opened a 10.9-kilometre CTrain line running from Anderson Road to Seventh Ave. SW one of the first municipal transit systems in North America to operate a light rail system. Over the years, the CTrain system has grown to encompass far-reaching areas of the city and now boasts 56.2 km of track between both the blue and red lines. The city plans to expand the LRT system with a green line that will run north-to-south, with funding from the provincial and federal government.

Similar to the proposed design of the new green line, which will have its downtown section underground, the original CTrain line was planned to run underneath Eighth Ave. instead of Seventh Ave. above ground. The tunnels were constructed but later abandoned after the city ran $23.3 million over their intended budget. In 2008, Global News reporter Doug Vaessen explored these tunnels with then-mayor Dave Bronconnier by climbing down a ladder from the City Hall parkade. Vaessen claimed the tunnels were made “to link the trains on the northwest and the south lines with the tunnel continuing down Stephen Ave. to 10th St.” The Calgary Herald poked fun at these tunnels in February of 2008, saying that these empty tunnels “will probably remain [as] just another lonely shrine to all of Calgary’s would-have, should-have, could-have dones.”

The City of Calgary has hinted at the potential of using these tunnels for future LRT expansion, but hasn’t yet made it clear if and how that would happen. Additionally, Seventh Ave.’s transit-heavy designation has made it a place where once-lively street activity has moved to malls and other indoor areas. In Stephanie White’s book Unbuilt Calgary, she describes how having sidewalks “squeezed by a street wall of either the inhospitable bases of office towers or downmarket pawn shops is all too narrow and too inconsistent.”

Political controversy also surrounds discussions around expansions to the CTrain system in the last decade. In 2010, Bronconnier abstained from making any decisions on the location of the West LRT Sunalta station, as he owned a commercial property whose value would increase by 15 per cent if the station was built nearby. In the end, council decided to include Bronconnier’s property within the area of rezoning. Bronconnier claimed to have owned that building since his days as an alderman in the ‘90s — around the time that redevelopment plans were in talks at City Hall.

A more recent political standoff took place during the 2017 mayoral election. Runner-up Bill Smith campaigned during the election on re-evaluating the already-approved green line LRT. At the time, provincial infrastructure minister Brian Mason told press outlets that funding for the project wasn’t guaranteed if details of the project changed. These are two examples of political battles surrounding and arguably shaping aspects of the city’s public transit infrastructure.

Looking ahead

Within the last 100 years, Calgary’s transit system has changed dramatically to keep up with the evolving demographic and urban form of the city. In many ways, the city’s transit has shaped the social landscape of the city and has encouraged certain lifestyles that are uniquely Calgarian.

The city has proposed a transit plan called RouteAhead that outlines a 30-year plan for the city to increase pedestrian-friendly areas, increase the frequency and accessibility of public transit and increase the sustainability of the system as whole. But beyond the to-be-built green line, there aren’t many specifics available about what the city’s public transit future looks like. Who knows? Maybe we’ll even develop a high-speed rail system between Calgary and Edmonton.

While it’s practically a local pastime to complain about Calgary Transit, the city’s transit system is worth celebrating. In the 2017 Transit Report Card of Major Canadian Regions, an annual grading of the country’s transit systems, Calgary received an A+ — on par with Vancouver and behind only Montreal. And while there is certainly more work needed to create a city that’s as mobile as we deserve, Calgarians should be proud of the 100 years that have gone into creating our current network.