Craigie Hall: The history of one of the U of C’s most contentious buildings

By Scott Strasser, July 26 2016 —

From the outside, the building looks prison-like, with its drab grey exterior and architectural simplicity. To those driving past as they round the University of Calgary bus loop, Craigie Hall probably doesn’t seem too out of the ordinary.

But those bland grey walls hold some of the U of C’s most controversial histories. Over the years, Craigie Hall has seen everything from insect infestation to a public asbestos scandal following the death of a U of C Spanish professor.

Curious about its multiple controversies, the Gauntlet decided to delve into Craigie Hall’s past. Here’s what we found.

[hr gap=”2″]

Early History

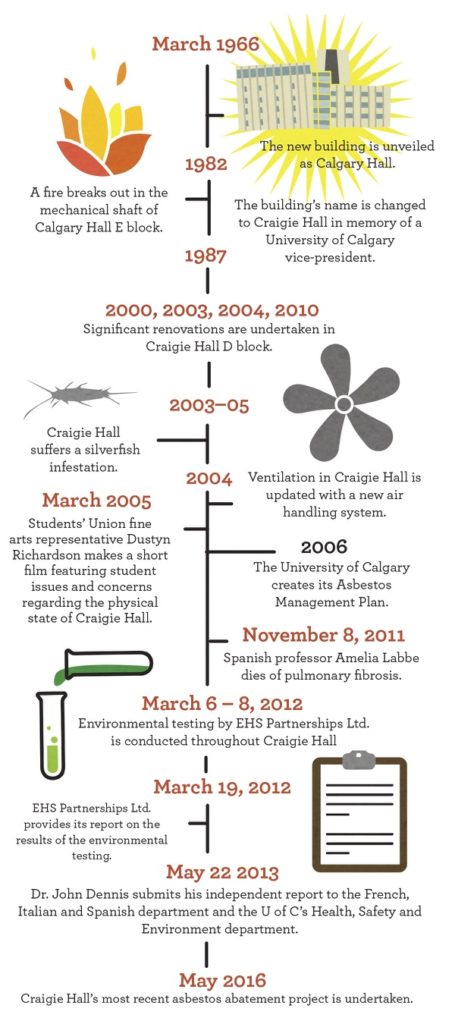

Craigie Hall is one of the U of C’s oldest buildings. It was built in 1966 and celebrated its 50th birthday this spring. The building’s construction cost $4.4 million and took just under two years to complete.

The building was originally named Calgary Hall, but its name was changed in 1987 to memorialize former U of C vice-president Peter Craigie. Today, Craigie Hall is home to the U of C’s drama and music departments, as well as the university’s linguistics and language-related disciplines.

The building’s first notable incident occurred in 1982 when a welder’s faulty work started a fire in the mechanical shaft of the E block. To this day, it is the only major fire to happen on the U of C campus. Restoration took approximately three months and the smoke and water damage cost around $1 million to repair.

But the real drama didn’t start until decades later.

[hr gap=”2″]

Asbestos Scandal

Amelia Labbe was a U of C Spanish professor who died of pulmonary fibrosis in November 2011. The disease causes scarring of the lungs and is often caused by airborne toxins and environmental pollutants.

Labbe’s family members told media after her death that doctors couldn’t pinpoint the cause of her disease, but they think it was from her work in the asbestos-laden Craigie Hall, where Labbe was the director of the department’s Spanish Language Centre.

Scott Strasser

“We still think something in that building made her sick,” said Labbe’s sister Noemi Flores. “She was a healthy person, there’s no history in our family of that disease. But she spent over 20 years in that building.”

The U of C has asserted for years that the air quality in Craigie Hall is acceptable.

“The U of C took all concerns from faculty and staff very seriously,” said associate vice-president (Risk) Rae Ann Aldridge. “All historical air monitoring in Craigie Hall confirmed that environmental conditions met regulatory requirements.”

At least 41 buildings at the U of C contain some form of asbestos. Until the 1970s — before bans and restrictions were put in place — the carcinogenic silicate was widely used in university construction projects. Flooring, drywall joint compounds, insulation and fireproofing could contain a form of asbestos.

“You will find asbestos in most government and public buildings throughout Canada and virtually every post-secondary institution across the country,” Aldridge said.

The Canadian government insists that if properly maintained and managed, asbestos-containing materials should not pose a serious health risk. But if asbestos-laden mineral dust is knocked into the air — such as during a renovation period — the particles are more likely to be friable, or pulverized. And inhaling friable asbestos particles can lead to health issues, including asbestosis, mesothelioma and other cancers.

Craigie Hall’s D block, which houses the department of French, Italian and Spanish, has seen four major renovations. The sixth floor was renovated in 2000, the fourth floor in 2003, the main floor in 2004 and the third floor in 2010.

The U of C upgraded the ventilation in Craigie Hall with a new air handling system to improve circulation in 2004. But it was during the 2003 renovation that Labbe’s family think she may have contracted her illness. They said it was a particularly dusty renovation.

“Everybody was worried for their health,” Flores said. “They didn’t know whether they should still be working there or not. I’m an outsider, I wasn’t working there. But they were all friends of my sister that worked together for many years.”

Not everyone agrees that contained asbestos is safe. A 2015 Globe and Mail story claimed that asbestos exposure is the “single largest on-the-job killer in Canada” and accounted for “more than a third of workplace death claims” approved in 2013. The Globe also reported that, from 1996 until 2014, almost 5,000 approved death claims were tied to asbestos exposure.

More recently, a Worker’s Compensation Board report claimed that 19 of 24 workplace-related deaths in Alberta in 2016 were related to asbestos exposure.

U of C Cumming School of Medicine professor Alain Tremblay said claims can be underreported, as it’s hard to definitively prove a disease’s root cause.

“For a common cancer like lung cancer, smoking will be blamed rather than asbestos, even if the latter is an important contributor to risk,” Tremblay said. “The latest Worker’s Compensation Board report had only one case of asbestos-related cancer. From epidemiological studies, [we] could expect 100 cases per year in Alberta alone.”

According to Tremblay, another reason asbestos-related deaths are underreported is that exposure can occur several years beforehand.

“[If] exposure is 30–50 years prior, the patient may not recall or realize exposure occurred,” he said.

Following Labbe’s death, her family and co-workers demanded an independent air quality review of Craigie Hall, which was undertaken by external consultant EHS Partnerships Ltd. in March 2012.

Those independent tests, which occurred over three days, showed Craigie Hall met occupational health and safety standards. The tests also showed the building did not contain asbestos.

More specifically, the asbestos air samples that were analyzed were “found to be less than 0.01 fibres per cubic centimetre and were below the criteria specified by Alberta Immigration and Employment.”

Emilie Medland-Marchen

“Asbestos was not detected on the tape lift samples,” reads the EHS report. “The surfaces sampled in Craigie Hall C and D were found to be free of asbestos contamination.”

Despite the investigation’s assurance that the building’s air quality was up to par, concerns among staff remained high. Professors from the department of French, Italian and Spanish and the U of C’s Environment, Health and Safety department later appointed an independent physician to analyze historical air quality data.

Industrial hygienist and risk assessment specialist John Dennis of SolAero Ltd. was asked to analyze historical data surrounding Craigie Hall’s health complaints from staff and air quality monitoring from as far back as 2000.

While not affiliated with the U of C at the time of his analysis, Dennis had held adjunct professor status within the U of C’s medical school from 2005–2010, offering occasional lectures in exchange for library access.

“He has no affiliation to the University of Calgary other than his past adjunct position,” reads the report.

Like the EHS investigation, Dennis found that asbestos presence was in line with occupational health and safety standards following the 2003 renovations. He concluded that “there [was] no evidence of potential occupational exposures within Craigie Hall, which would result in exposures above regulatory guidelines.”

Dennis’ investigation also acknowledged that “there [was] a high prevalence of cancer amongst staff working within Craigie Hall blocks C and D.” According to his report, cancer prevalence among Craigie Hall employees was much higher than would be expected in the general population — at or above the 96th percentile.

The report claimed the high cancer presence was “most likely an unfortunate statistical anomaly that will occur in a minority of instances within a population.”

Flores said she knows many professors in Craigie Hall who contracted cancer and other illnesses, but admitted it’s impossible to prove it was from working in the building.

“We cannot say they contracted [it] because of that. I think they did, but I’m not an expert. But yes, several people got sick working in Craigie Hall,” she said.

In his report’s recommendations, Dennis wrote that Craigie Hall staff working in blocks C and D should “accept that increased cancer rates evident in the department may well be due to chance alone, and not associated with occupational chemical exposures within Craigie Hall.”

Even after multiple investigations had shown Craigie Hall’s air quality was acceptable, staff in the department of French, Italian and Spanish remained concerned and frustrated.

Emilie Medland Marchen

Dennis interviewed multiple staff, students and faculty throughout his investigation. While confidential in nature, his report acknowledged that “many Craigie Hall staff have been and are concerned that there may be some chemical exposures associated with Craigie Hall blocks C and D which may be the cause of cancers.”

The U of C was not unprepared for an asbestos scandal, having created an Asbestos Management Plan in 2006. Asbestos abatement projects now occur four times per week on average at the U of C and follow protocols from the Alberta Asbestos Abatement Manual.

Aldridge says the U of C’s Asbestos Management Group operates independently of the Project Management Office and has one full-time asbestos coordinator, who facilitates all abatement activities. The university also retains an independent third-party consultant who provides direction and oversight.

“The university’s standards for asbestos management are designed to meet or exceed all provincial regulations and best practices to support the health, safety and well-being of students, faculty and staff across all university campuses,” Aldridge said.

According to Aldridge, there were three abatement projects undertaken in Craigie Hall in 2015–16.

“We’ve undertaken a proactive abatement project in Craigie Hall C, a maintenance-related abatement in Craigie Hall D and a construction-related activity in Craigie Hall G,” she said. “Two of these projects were minor in nature and short in duration.”

[hr gap=”2″]

Student Issues

Craigie Hall’s controversies don’t end with its air quality issues. As it’s aged, the building’s worsening physical state has garnered backlash from the student body.

The building’s basement suffered a silverfish infestation in 2003–04. Silverfish are small, teardrop-shaped insects that commonly infest dark and damp areas. While not a health threat, they are infamous for their destructive feeding habits, seeking out glue, paper and sugar to eat.

Silverfish are nocturnal and reproduce quickly. According to media reports, the infestation at the U of C had to be dealt with repeatedly by pest control professionals.

Drama students who practiced and studied in the basement of Craigie Hall were particularly annoyed by the silverfish, who were often seen scurrying across the floor.

Emilie Medland-Marchen

“It’s a real problem down here,” said Drama Undergraduate Society director Braden Griffiths in an NUTV segment from March 2004. “We spend a lot of time on the floor, working physically. It gives me the willies to think there are these tiny little insects crawling around, infesting our basement.”

Former dean of drama Ann Calvert was also interviewed for the television segment.

“It’s certainly a problem with old buildings on any university campus,” said Calvert. “We’ve got bugs. We’ve got to get rid of them.”

In 2005, then-Students’ Union fine arts representative Dustyn Richardson made a short-film featuring other issues students had with Craigie Hall. Richardson created the video as a bid for a portion of the money the SU received for a campus improvement fund that year.

Emilie Medland-Marchen

“After speaking to the heads of the student clubs and the general arts student body, and being an arts student myself, I realized this fund might be a great way for us to see tangible improvements to our ailing work spaces,” Richardson said. “The problem was that outside of our small faculty, there wasn’t any awareness of just how lacking our learning and creating spaces were. Hence, the video.”

The video featured many complaints from fine arts students who spent their days in Craigie Hall. Issues included speakers that didn’t work, soundproofing falling off the walls and ceiling leaks, along with sparking electrical outlets and broken heating in some of the music practice rooms.

One student in Richardson’s video remembers sitting in class while a worker drilled through the ceiling from above. The student said the worker filled the hole with caulk, which fell in a pile on the classroom floor below.

Students also brought up the silverfish issues from the year before.

“When [my video] was presented to the student council, I remember quite a few people being surprised at the state of the facilities,” Richardson said. “We ended up securing a portion of the fund — I can’t remember the exact figure — for student space improvements.”

[hr gap=”2″]

The Future of Craigie Hall

According to Aldridge, since May 2010, there have been 10,532 work requests completed in Craigie Hall. Those work requests — which Aldridge says include preventative and demand maintenance — have cost the U of C approximately $2.1 million and equated to around 20,500 hours of labour.

Aldridge says there are no immediate plans for further development of Craigie Hall. She said the building will remain at the U of C and will not be demolished.

Building demolitions are rare at the U of C, but have occurred before. Three residence buildings — Brewster Hall, Castle Hall and Norquay Hall — were demolished in the spring and summer of 2015.

The Nickle Arts Museum was demolished in 2013 to make way for the Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning. All of the museum’s art is now located in the Nickle Galleries on the main floor of the Taylor Family Digital Library.

Aldridge did acknowledge that another building could eventually replace Craigie Hall.

“Based on the U of C’s Long Range Development Plan, it is proposed that another academic building would take its place sometime in the future,” she said.

In the meantime, Craigie Hall is here to stay. Professors in the department of French, Italian and Spanish will never know for sure if working in Craigie Hall contributes to the department’s high cancer rate.

And for the family of Amelia Labbe, the building will forever be a reminder of a sad and frustrating time.

“All we hope is no one else there gets sick,” Flores said.

Samantha Lucy